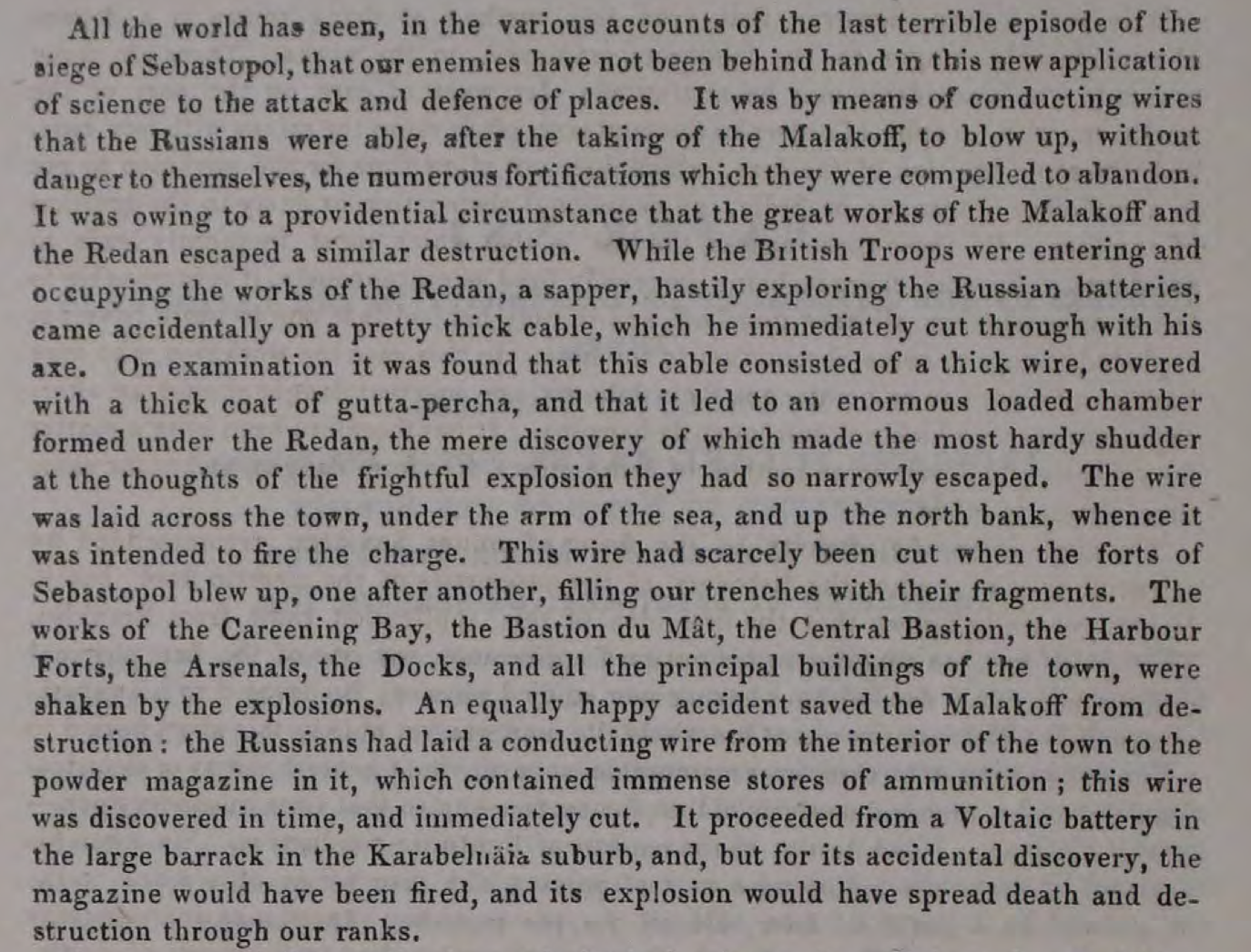

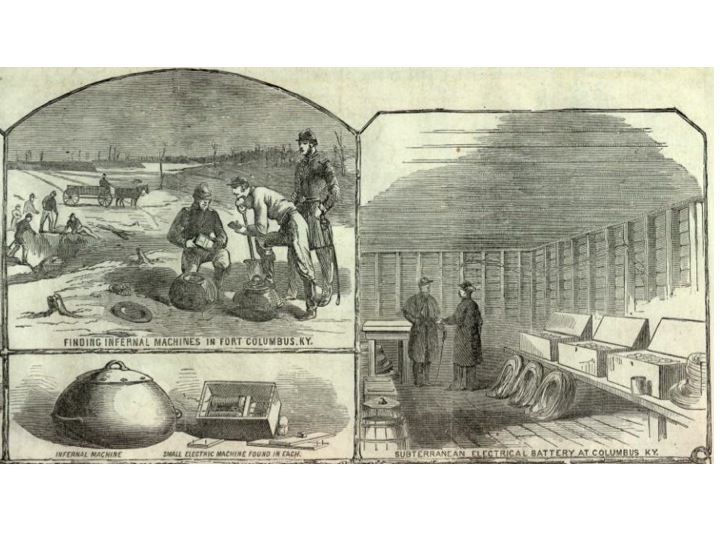

In my last post I discussed a massive electrically initiated command wire IED from the Crimean war in 1856. This article is about a massive command-wire device in Charleston during the American Civil War in 1863. I’ve been finding stuff on explosive devices during that conflict for a few years now, but this one is new to me, possibly because it failed to explode. Importantly I think this IED was the biggest ever seen in the USA – perhaps my US colleagues would care to comment.

This Confederate device was constructed using an entire ship’s steam boiler as a container. It was packed with 5000 pounds of blackpowder (other reports suggest 3000 pounds) and sunk in 6 fathoms of water 1500 yards off Fort Sumter, just outside Charleston, South Carolina. Insulated electrical cables led from the boiler to an electrical charge generator in the Fort, defended by Confederate Forces. There had been a series of naval bombardments of the Fort over several months. On 8 September 1853 the Federal Navy approached the Fort again to bombard it. The flagship “New Ironsides” placed itself directly above the device and fired nearly 500 rounds at the Fort. Every attempt was made to initiate the device but it failed to function. After 90 minutes the Ironsides moved off. The device had been in place for 4 months before it was attempted to fire. The man responsible for testing the circuit daily was put in irons, although he claimed he had circuit tested it the previous day. Probably there had been an ingress of water or there was insufficient voltage. But 5000 pounds of powder exploding a few feet underneath a battleship would have been quite an attack.

Here’s a report on the laying of the device, which suggests that the resulting cable length was over a mile longer than expected – perhaps the power source was insufficient to cope with that:

The torpedo was successfully sunk on the spot located by General Ripley, but while running the cable the steamer (Chesterfield) ran out of steam, and, unable to hold against the tide and wind, went aground near Fort Sumter. On the increase of the flood we had to run back a long circuit reach Cummings Point and land the cable. It resulted from this accident that we played out 2 miles of cable, instead of 1, as expected.

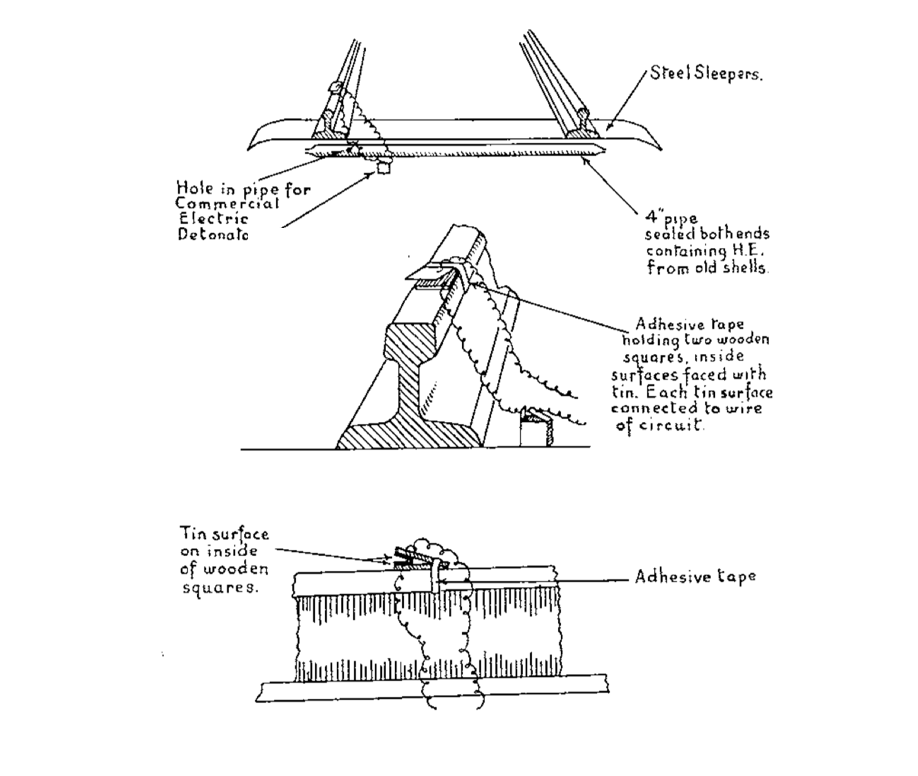

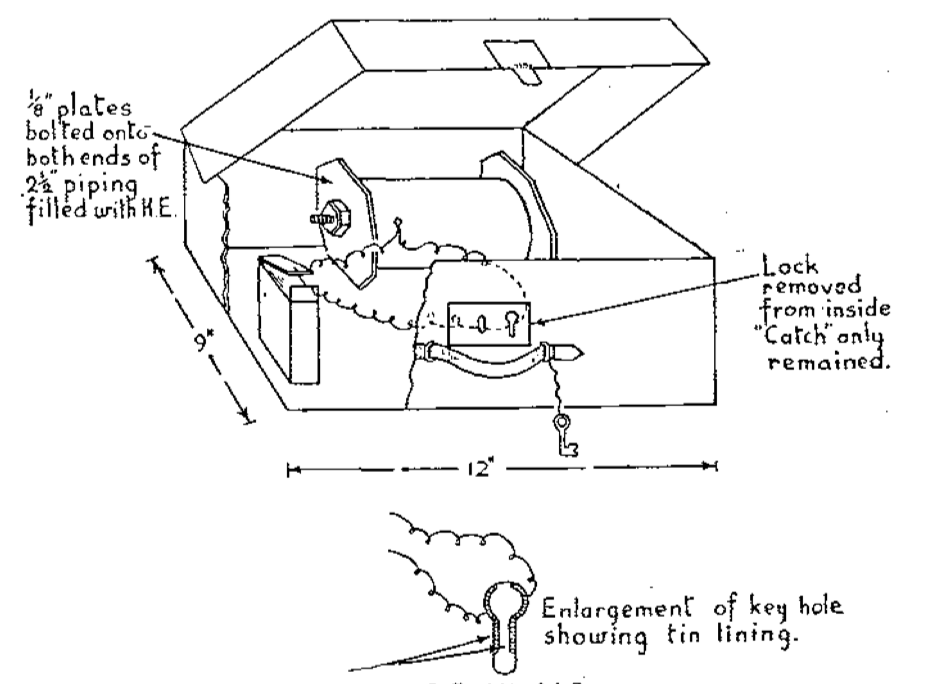

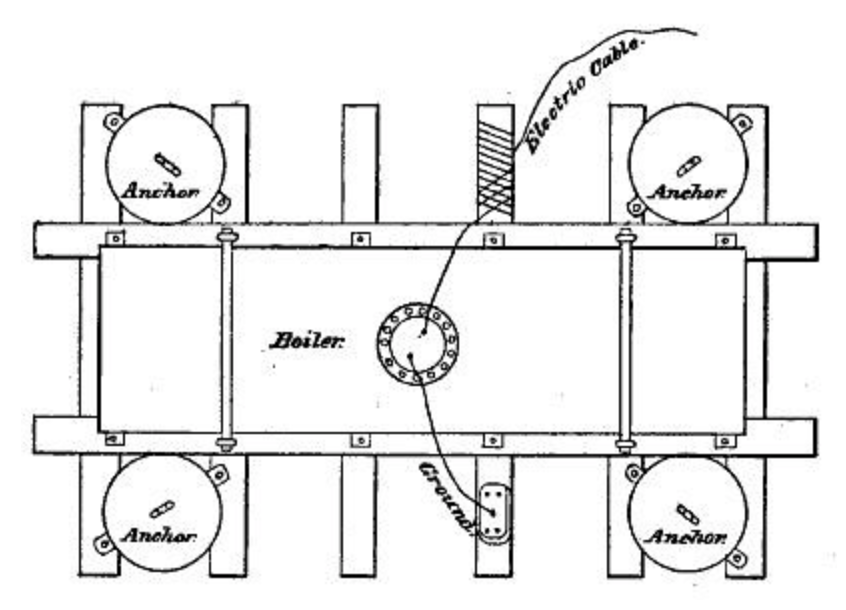

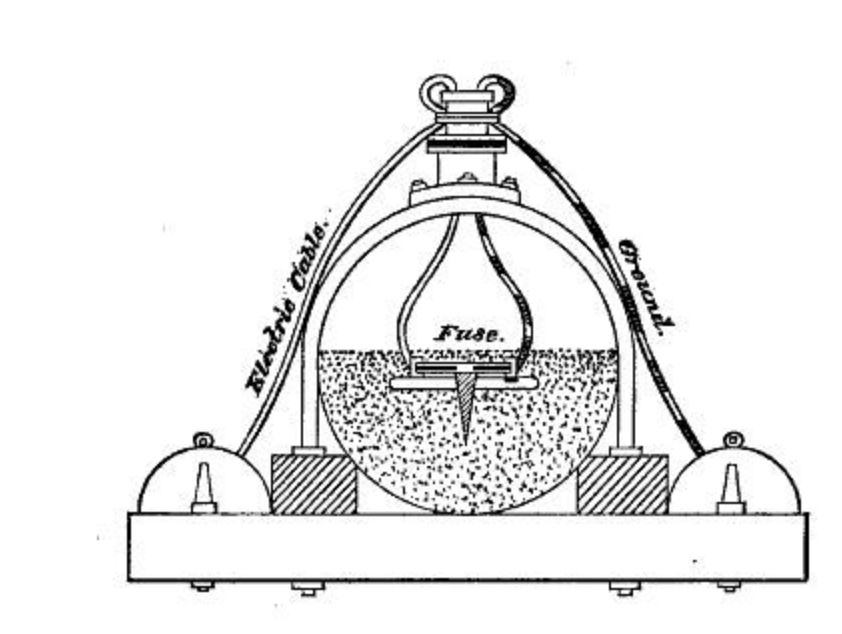

Here’s a couple of diagrams of the explosive device, which I think are contemporary:

The boiler, full of powder, is probably still there…

There is some mention of the use of powder filled boilers being used unsuccessfully on the James River by the Confederate explosive expert Captain Maury at an earlier time during the Civil War. Apparently the boilers were not anchored well and moved in the current, parting the electrical cables. Captain Maury’s electricity generator apparently “weighed nearly a ton” which also made the devices awkward to deploy. Maury was later sent on a mission to England to procure better electrical power sources (in modern parlance, “IED components”) from the scientist Sir Charles Wheatstone.

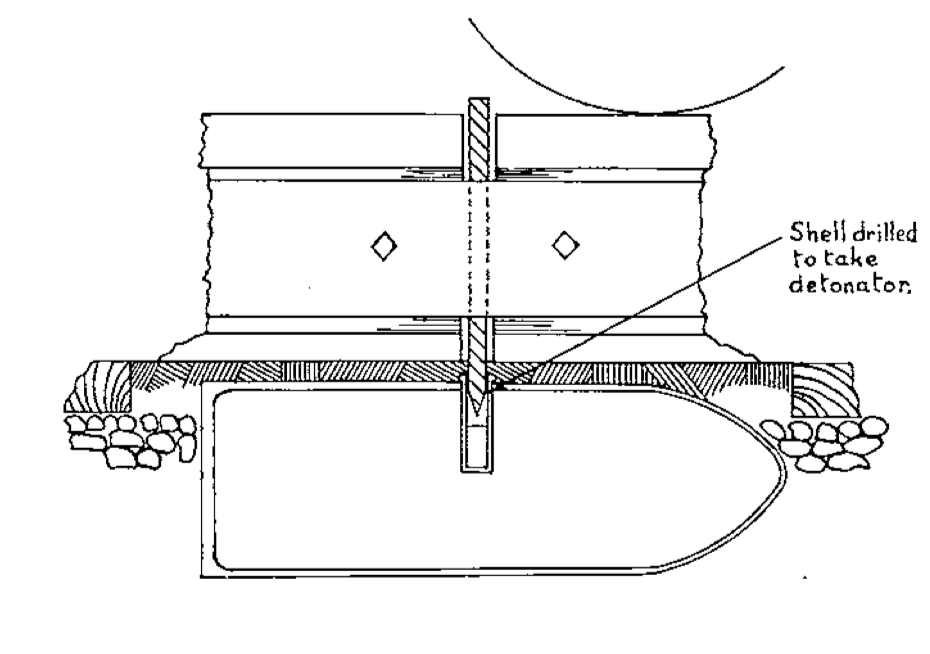

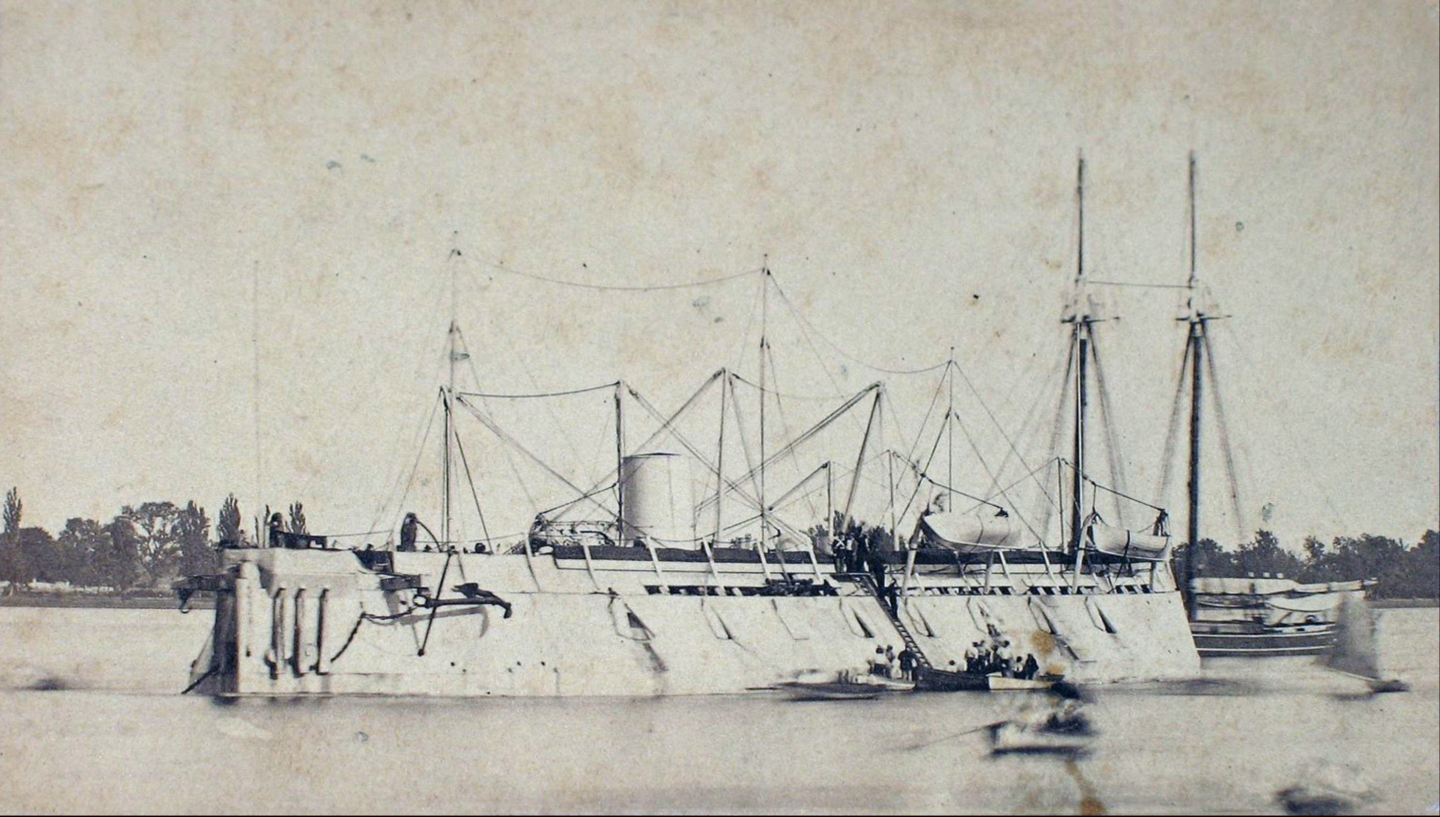

Fort Sumter in August 1863, a month before the incident:

Here’s the USS New Ironsides, the target of the IED:

I have found some new material on underwater Confederate devices used to prevent Federal ships moving up the James River subsequent to Captian Maury’s boilers, but I need time to check this new material against other records. I’ll put up a post at some time in the future when I have time.

In one of those strange “mirrorings” in history the following year it was Union forces who considered use of a massive IED against Fort Sumter. Union commander ,Major-General John Foster had in mind a plan to level Fort Sumter by way of a large explosive device. “As soon as a good cut is made through the wall,” Foster wrote to Washington on July 7, 1864, “I shall float down against it and explode large torpedoes until the wall is shaken down and the surrounding obstructions are entirely blown away.”

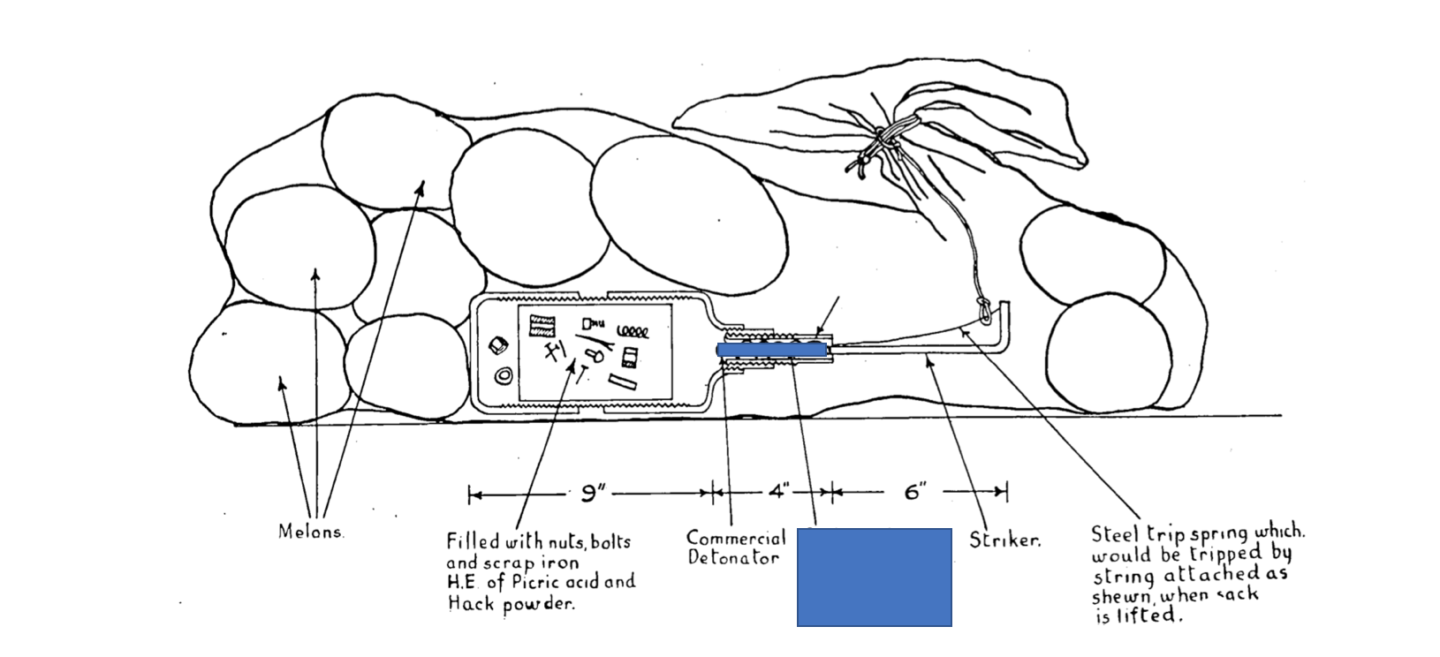

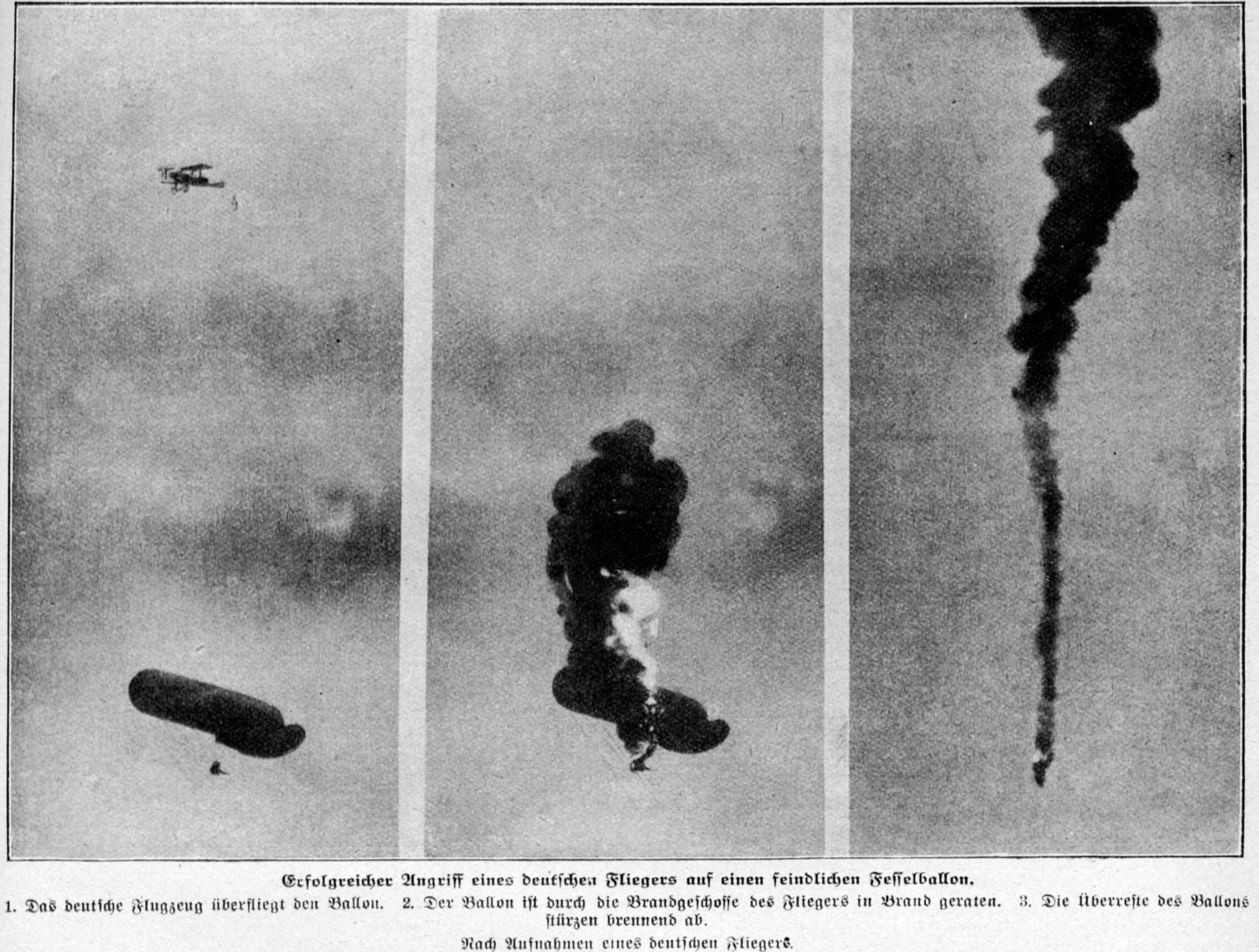

Later that month Union naval forces had made a “cut” in a protective wall and pushed an explosively-laden barge towards Fort Sumter. But due to miscommunication and bad weather the attack was abandoned. Other attempts were then made in August 1864 by land forces using improvised rafts, laden with explosives and initiated with timing devices. These were to be pushed into place by boat. Here’s one contemporary report:

On the night of the 28th ultimo, a pontoon-boat, fitted up for the purpose and containing about twenty hundredweight of powder, was taken out by Lieut. G.F. Eaton, One hundred and twenty-seventh New York Volunteers, boat infantry, and floated down into the left flank of Fort Sumter. The garrison of Sumter was alarmed before the mine reached them, and opened upon our boats with musketry, without, however, doing them any injury.

The device exploded, but in the wrong place and too far away to cause significant damage. Then:

On the night of the 31st ultimo six torpedoes, made of barrels set in frames, each containing 100 pounds of powder, were set afloat with the flood-tide from the southeast of Sumter with the view of destroying the boom. They probably exploded too early and only injured perhaps two lengths of the links of the boom, which are now not visible.

Another attempt was made the following night on 1 September 1864, the device exploded but again causing no significant damage.

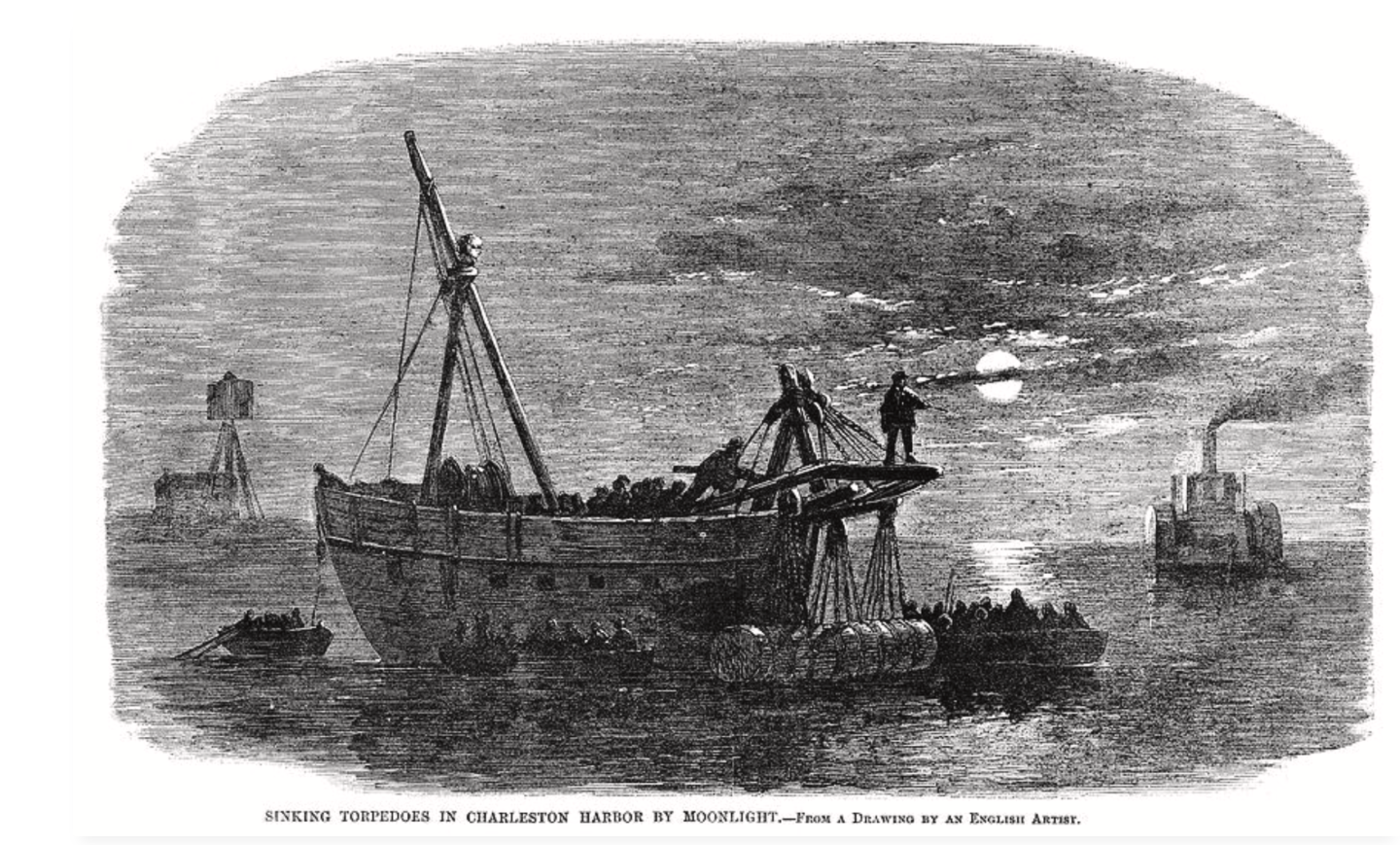

Here’s a drawing of the devices being launched:

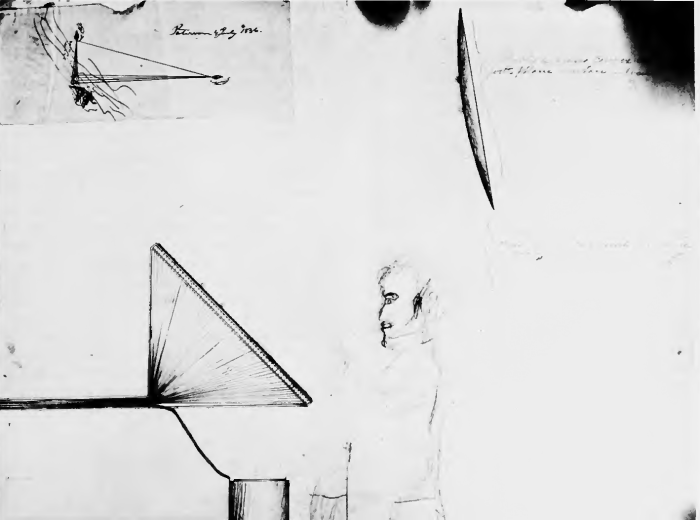

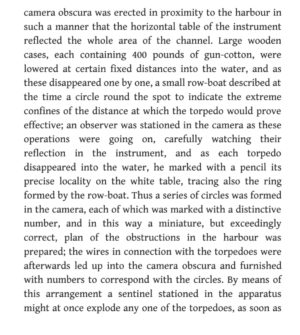

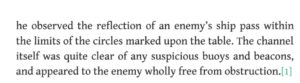

I also have found some new interesting technical material about very large submerged electrically initiated devices used in the defence of Venice, in 1859, that appear also to have used Samuel Colt’s “Camera Obscura” command post technique – again to follow when time permits. I continue to view Samuel Colt’s amazing explosive device initiation command post of 1836 as one of the most remarkable things I have ever come across in all my research.