Over the past few months I have been in conversation with a new Indian friend, Mr Nidhin Olikara. He has done some tremendous work with archaeological colleagues on some ancient rockets recently discovered from the time of Tipu Sultan, in the late 1700s in India. These metal cased rockets predate any European metal cased rockets, and were, I believe a source of technology for Congreve’s rockets, developed at Woolwich in England in the early 19th century. Congreve gave little or no credit to the Indian technology which he exploited, and no credit at all to the Dublin rebels’ rockets, which I believe were also inspired by the Indian rocket technology.

This is a complex story of industrial history, archaeology, munitions exploitation, technical intelligence, metallurgy and ordnance design. For context, I have written before about European rocket development here:

http://www.standingwellback.com/home/2018/5/2/the-history-of-metal-cased-military-rockets-an-investigation.html

and Robert Emmet’s rockets in Dublin in 1803 here:

http://www.standingwellback.com/home/2012/12/28/the-mystery-of-the-the-man-with-no-history-other-spies-and-e.html

Mr Olikara and his colleagues came across many rockets which appear to have been disposed of down a well. They have been able to recover these and examine them scientifically and the results are fascinating. They have written a paper recently published in the Journal of Arms and Armour Society, Volume 22, No 6, dated September 2018. It is not yet available on-line.

Rockets were developed in India by the forces of Haider Ali and then his son Tipu Sultan in the late 1700s. They were used extensively against their enemies, including the British. Amongst Tipu Sultan’s allies, were the French, which may be relevant for later parts of this story. It appears that the British recovered some of these metal cased rockets to Woolwich Arsenal.

Some of the 160 rockets that Mr Olikara recovered have now been analysed and the results are fascinating. A quick summary:

- a. The rockets are largely of a similar dimension to the (later) first of Congreve’s rockets, varying in diameter between about 35mm and 65mm

- b. They appear to be made of what we would call today “mild steel”. ie relatively low carbon content. This would make the metal relatively malleable.

- c. The assessment is that the cylinder components of the rocket were hot or cold forged on a cylindrical die or anvil, with two end caps (one with a vent) forged onto the ends. To be clear, the base material is a rectangle of sheet mild steel, hammered on a cylindrical anvil into a tube shape and two flat circles then attached to the ends, by hammering. One of these ends has a central vent acting as a venturi choke.

- d. Remarkably the contents of the rocket were still largely present and chemical analysis gives results consistent with gunpowder/blackpowder. In some rockets there is still a clear suggestion of a formed central combustion chamber formed in the propellant.

- e. Perhaps most interesting of all, from a munitions design perspective is that the rockets appear to have been lined with a refractory element such as clay, providing a layer between the explosive/propellant fill and the steel wall of the rocket. Most intriguing. I can find no reference of a similar fabrication in later Western rockets

What is still unclear is the filling process in relation to the fixing of the end caps. What came first? Fixing the end caps first makes sense from a safety perspective but makes the filling process tricky. I expect it will depend on the nature of the filling and how easy it was to load it in the cylinder. I suspect that the front end cap was fixed first, and the rear closing cap fitted “snugly” then removed, the rocket then lined with clay, dried, and the powder fill put into place. The combustion chamber would then be bored, the rear cap affixed in some manner (carefully) so as to not ignite the charge, and a fuse made of some sort of cloth inserted in the nozzle/venturi.

What is also is unclear is how the longitudinal seam of the rockets metal cylinder body was formed. I suspect it was “folded” in a “finger lock seam”. To do this, (and speaking as a very amateur blacksmith), the two sides of the rectangle to be joined would be first turned and folded back a few mm on the edge of an anvil into a lip. When the sheet is then formed into a cylinder these folded turns would interlock. I will experiment in my own forge in coming days and try to post pictures.

I think the implications of these findings might be as follows:

- The Armies of Haider Ali and Tipu Sultan had an industrial level production firstly of mild steel in sheet form. I doubt this was “ rolled” steel but was probably very skillfully hammered. what is most significant, I think, is that the steel was being produced for a “ disposable”, one-time-use system. That indicates that sheet mild steel which heretofore was perhaps an expensive luxury for body armour of the rich and wealthy was available in such quantities in its sheet condition to be economic to make into one-time-use discardable munitions. I think that’s quite significant.

- This was proper industrial scale production of steel components, albeit the rocket diameters seem to vary. The skills in hot and cold forging mild steel are not dissimilar to the making of protective armour. The history of technology of India in a broader sense has often been ignored or discounted by the West. India’s metallurgical developments of such things as pure wrought iron, mild steel, carbon steel and Wootz steel is fascinating and the technological processes associated with manufacture of items from these materials seems to have been often ignored in history. This book https://www.amazon.co.uk/Indian-Oriental-Military-History-Weapons/dp/0486422291 published originally in the middle of the 19th century gives some insights into the broad range of military metallurgy in India over a number of centuries.

- The technology is well in advance of European rocketry which did not use metal cases (apart from the Emmet rebellion in Dublin in 1803), until 1805. Congreve, a man of his time, was disinclined to give credit to India, Emmet the Irish Rebel or indeed others (a Scotsman also claimed to have sent him the idea of metal cased rockets.) Congreve was driven of course by the opportunity to make a considerable fortune and reputation. Also, perhaps the role of technical intelligence from one’s enemies was, as it still is, always understated.

This development, like all good historical stories, prompts further questions:

- How did the French alliance with Tipu Sultan allow them to obtain metal cased rocket technology and pass such technology down to manufacturing instructions to Emmet in 1802/1803?

- Why did the French (at the time renowned for their scientific expertise in military matters) not develop rockets themselves until after Congreve had? French interest approved by Napoleon seems to have started in about 1809.

- What was the level of input into Congreve’s development from Irish rebel Pat Finnerty, Emmet’s rocket maker who ended up working for Congreve at Woolwich in 1804?

- What earlier (non-metal cased) rocket experiments at Woolwich by the British artillery general, General Desaguliers was Congreve able to draw on. He would have been aware of these experiments I’m sure, which had occurred some years earlier but were deemed a failure. But much would perhaps have been learned about propellant.

- Was there any technology transfer in the other direction? Mr Olikara and his team found what I am certain is a rocket boring tool in their investigation, used to bore a combustion chamber in the packed rocket body – it is remarkably similar to tools used in European rocket making in the 1600s…also, steel rolling mills were developed in Europe in the latter part of the 1700s… is it possible that this technology transferred to India, enabling the production of quantities of sheet steel for the rocket bodies? Or did Tipu Sultan simply reply on a large number of people involved in the manufacture, hammering out sheet steel with such skill?

Mr Olikara has also, interestingly and separately from the paper, found records of what I take to be a British military EOD operation in 1871. The operation involved the disposal (by an Ordnance officer) of cannon from the time of Tipu Sultan (70 years earlier) and mentions finding rockets that were still filled with propellant from this time. One of the cannon exploded (still loaded from 70 years earlier) while it was being prepared for destruction, killing one man. So in 1871, Ordnance EOD operations were dealing with dangerous munitions from earlier wars… Plus ca change!

The development of military rockets by Congreve and subsequently by quite a number of European and American nations continued throughout the 19th century, slowing when artillery systems improved, but there was certainly some sort of rocket arms race as Congreve, then Hale developed British rockets systems and the Europeans raced to get ahead. Even today it is possible to see in very real terms the evolution from Mysorean rockets to Congreve, to Hale and all the way through to say a modern Russian 107mm rocket system – and such systems are being adapted for improvised systems in Syria and Iraq today with much effect. Military metal-cased rockets are a staple of modern warfare, but now the nature of its origins in India is somewhat clearer. Those wishing more detail should obtain Mr Olikhara’s paper (I may be able to help), and also a book “The First Golden Age of Rocketry by F H Winter is a useful reference.

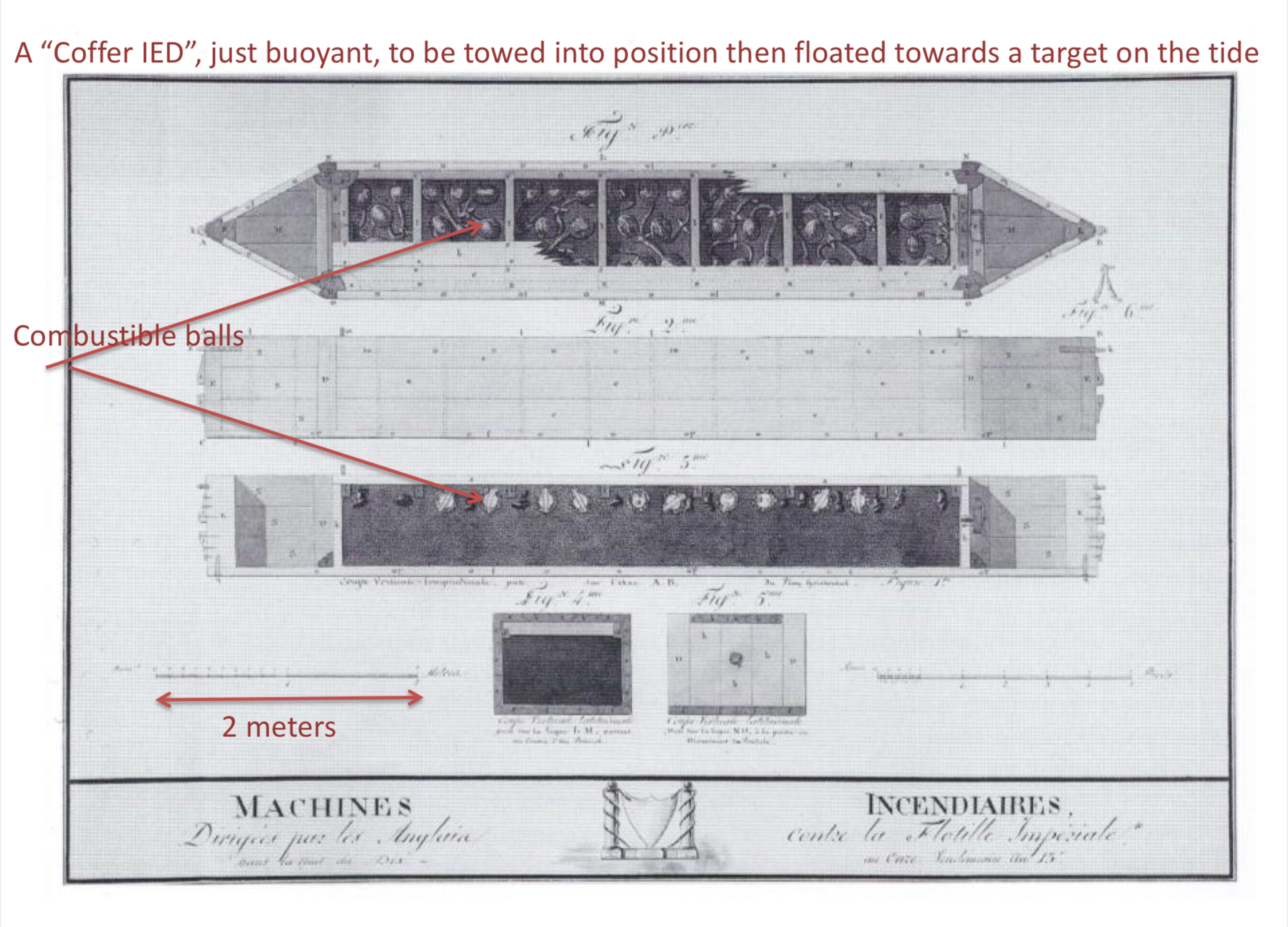

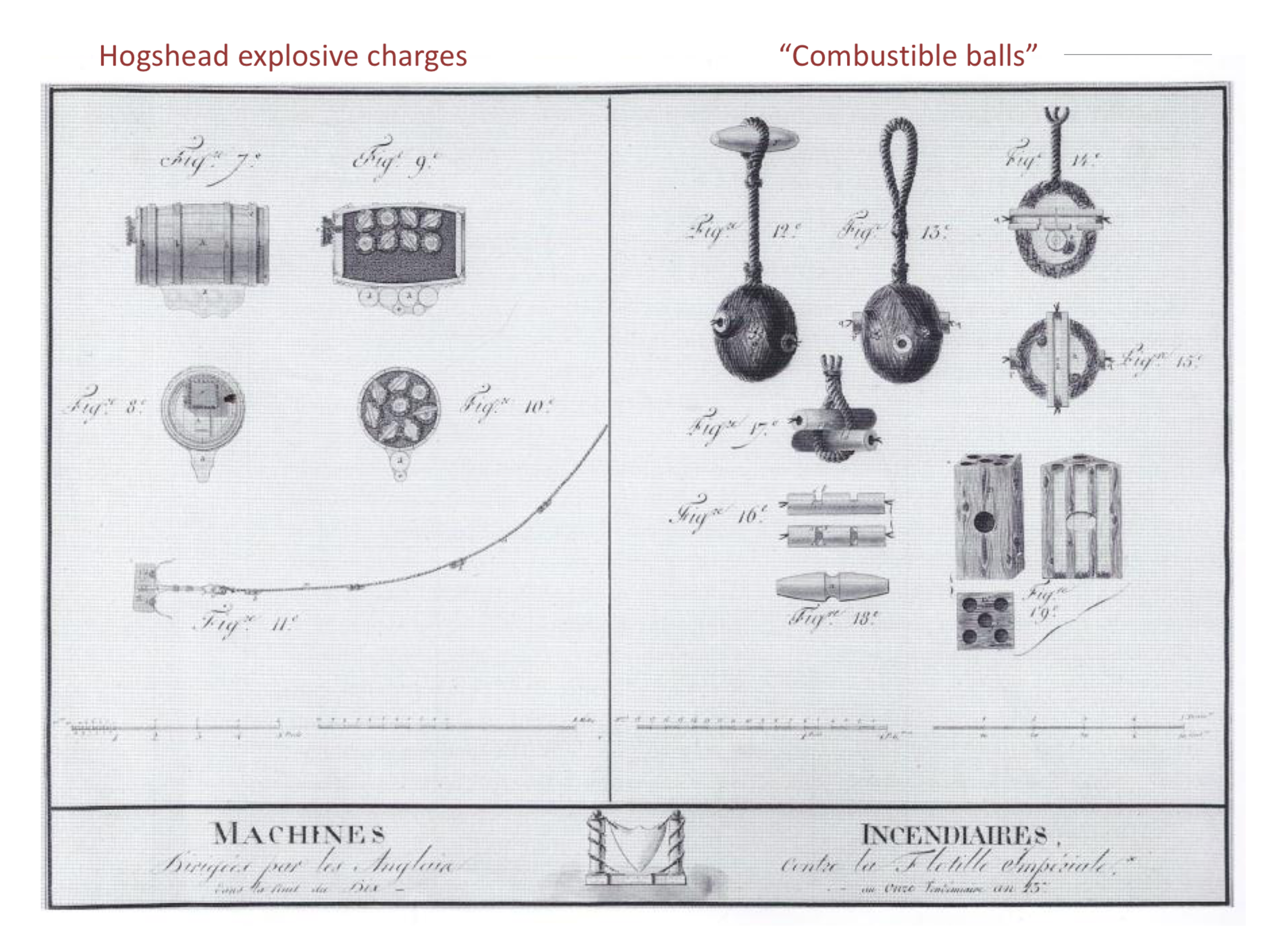

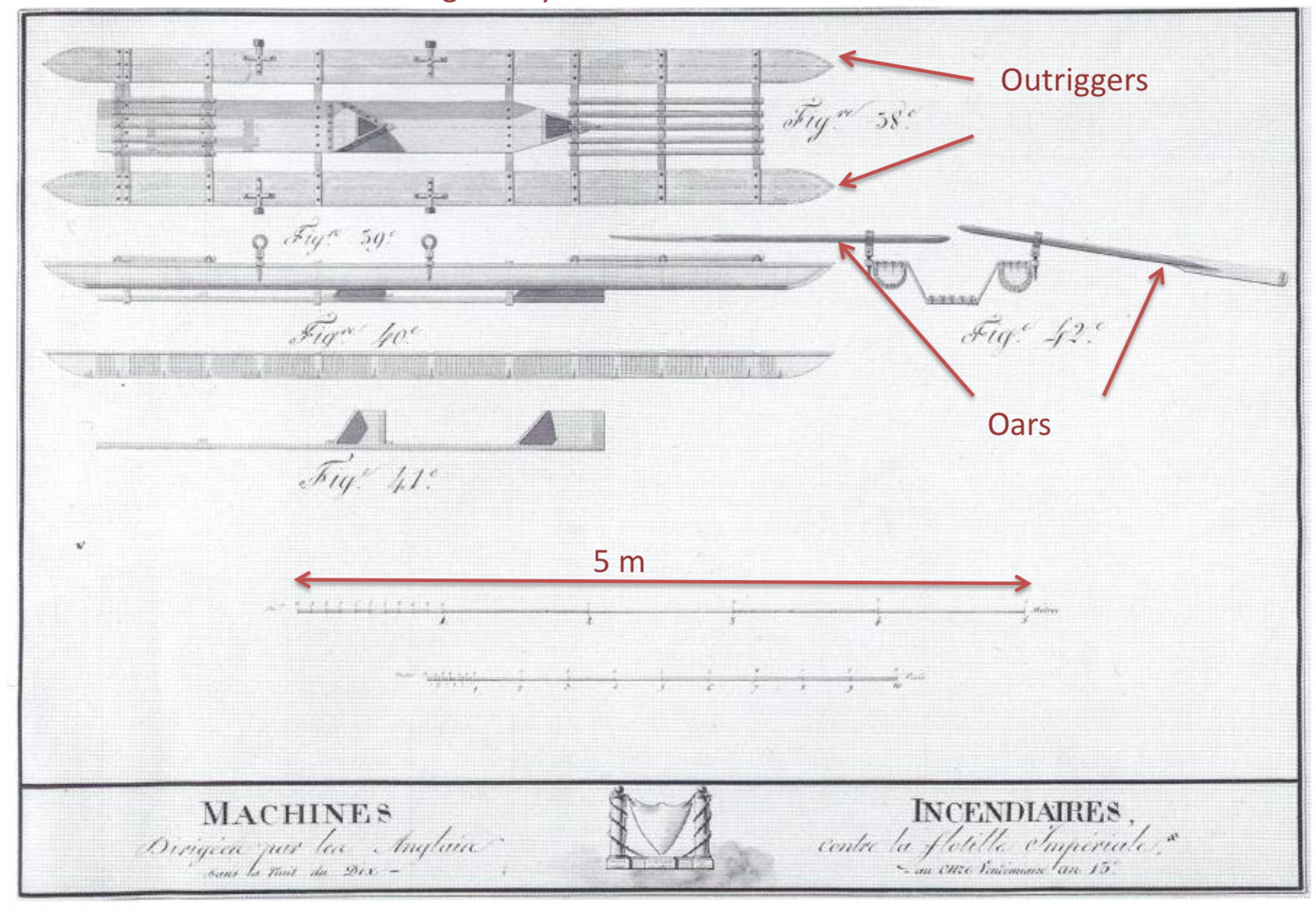

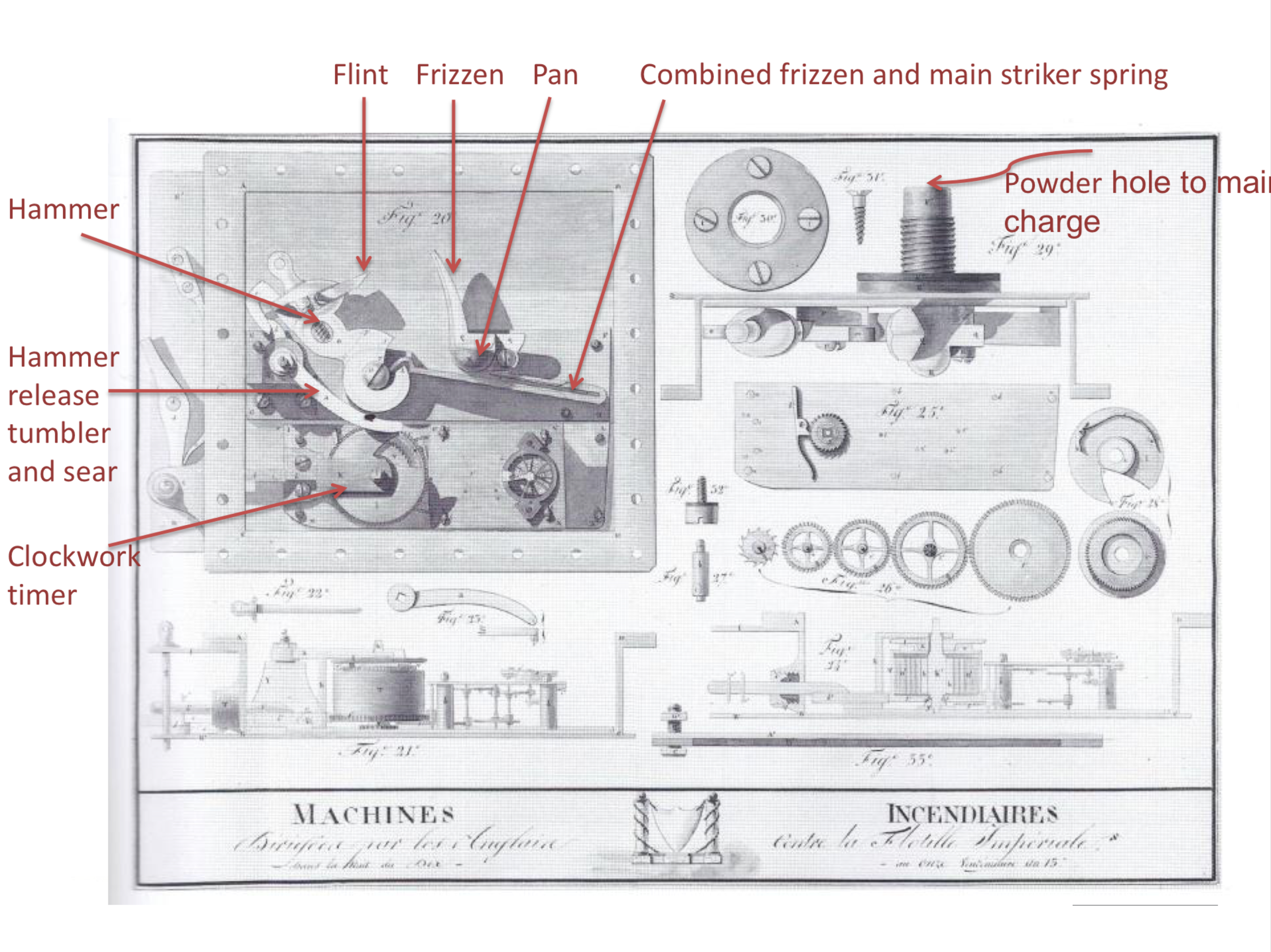

This clockwork initiation mechanism was attached to a main explosive charge. The main charge was a large sealed canoe shaped pontoon, described as a coffer. Two of these were attached to make a barely buoyant twin raft with a rowing position in the middle.

This clockwork initiation mechanism was attached to a main explosive charge. The main charge was a large sealed canoe shaped pontoon, described as a coffer. Two of these were attached to make a barely buoyant twin raft with a rowing position in the middle.