Some more detail of an early IED attack attempt that I had heard about but which I didn’t have much detail of until now. I mentioned in my post a couple of years ago here (Bomb Alleys) about an assassination attempt on Oliver Cromwell, with a device designed to burn down Whitehall Palace and I’ve found a few more details in the transcripts of the trial in ” Cobbett’s Complete Collection of State Trials and Proceedings etc Volume 5, pages 842-872″. It seems this was a successful EOD operation as part of a complex counter-terrorism operation. What a curious world counter-terrorism was in those days – as it remains today.

Cromwell – the target of the assassination attempt

The counter-terrorism operation was run by Oliver Cromwell’s spymaster, John Thurloe. The protagonist in this was one Miles Sindercombe, whose pseudonym was “Mr Fish”. Sindercombe appears to have been funded by a rebel puritan officer, Colonel Sexby, from the Netherlands. After four plans to ambush Cromwell had failed, Sindercombe decided to burn down Whitehall Palace, where Cromwell was living, in the hope that it might kill him. The device he used was constructed “by a man sent from overseas”.

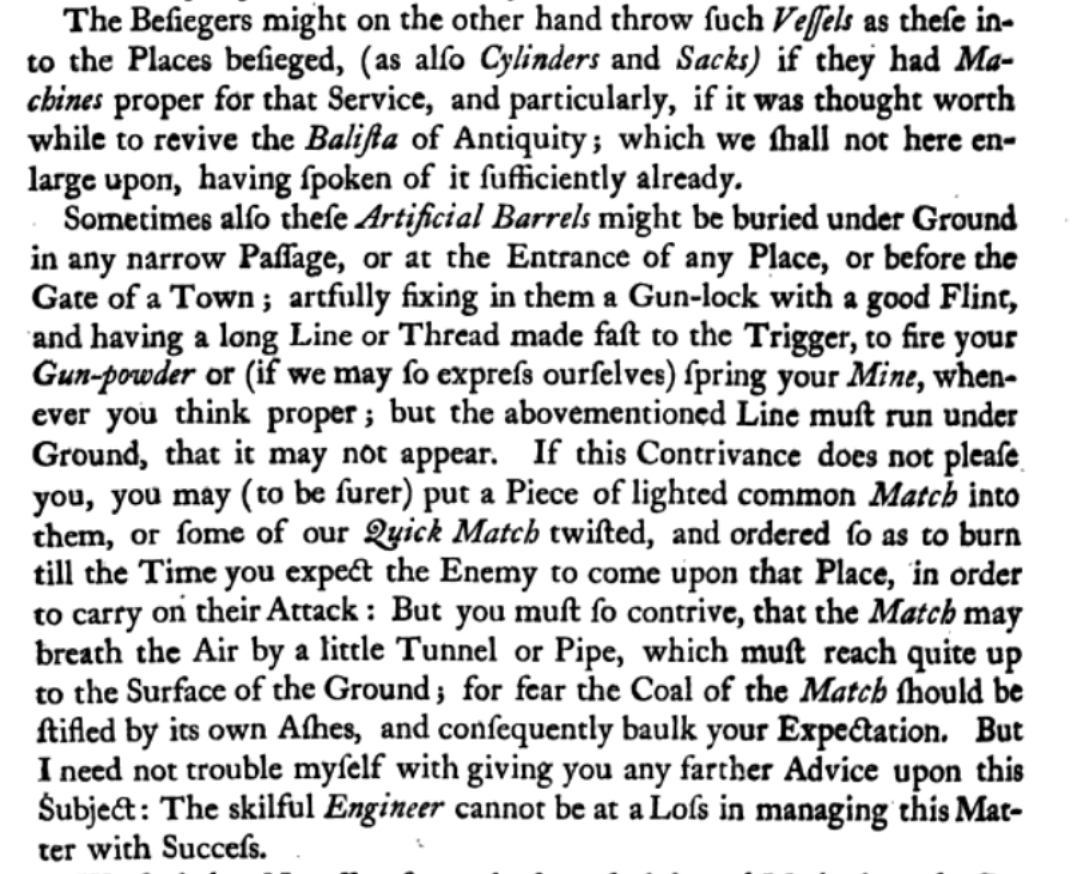

The device was in a wicker basket, and contained, a gunpowder charge, and “tar, pitch and tow” and “brimstone” to add an incendiary component. It had two “slow match” burning fuses in parallel with an expected delay of about 6 hours. That’s quite a delay for a burning fuse. The device was left in a chapel in the Palace (now the site of the UK Ministry of Defence, and buildings in that area), which Sindercombe had reconnoitered by attending a service earlier. On 8th January 1657, Sindercombe and his accomplices gained entry via a back door into the chapel, and hid the device under a seat. They lit the fuze and left the premises. However Sindercombe’s cell had been penetrated by government agents working for Thurloe and the authorities were alerted. The Palace Guard “found” the device and the Officer of the Guard rendered it safe by removing the burning fuzes.

Sindercombe was injured resisting arrest the following morning, and refused to co-operate. However all his co-conspirators did cooperate, gave testimony and Sindercombe was found guilty and sentenced to death a month later. He escaped the gallows by committing suicide by poisoning but suspicion remains he was killed to prevent a riotous public assembly at the execution. There are details of a rather bizarre post-mortem conducted some time after he had been buried beneath the gallows with a stake through his heart.

The details of his earlier assassination attempts on Cromwell are also intriguing. In one he hid an arquebus and pistols “in a viol case” (very 1920s…). In another, a purpose built firearm was to be used, described as a “strange device” that fires 12 bullets and a slug at the same time. Peculiar.

It’s surprising to me that this assassination attempt of the de facto head of state is little known about. Whitehall Palace – a mish-mash or architecture and complex passages , built mainly from wood did eventually burn down fifty years later. During the attempt to put out that fire in 1698 gunpowder charges were used to try to create firebreaks.

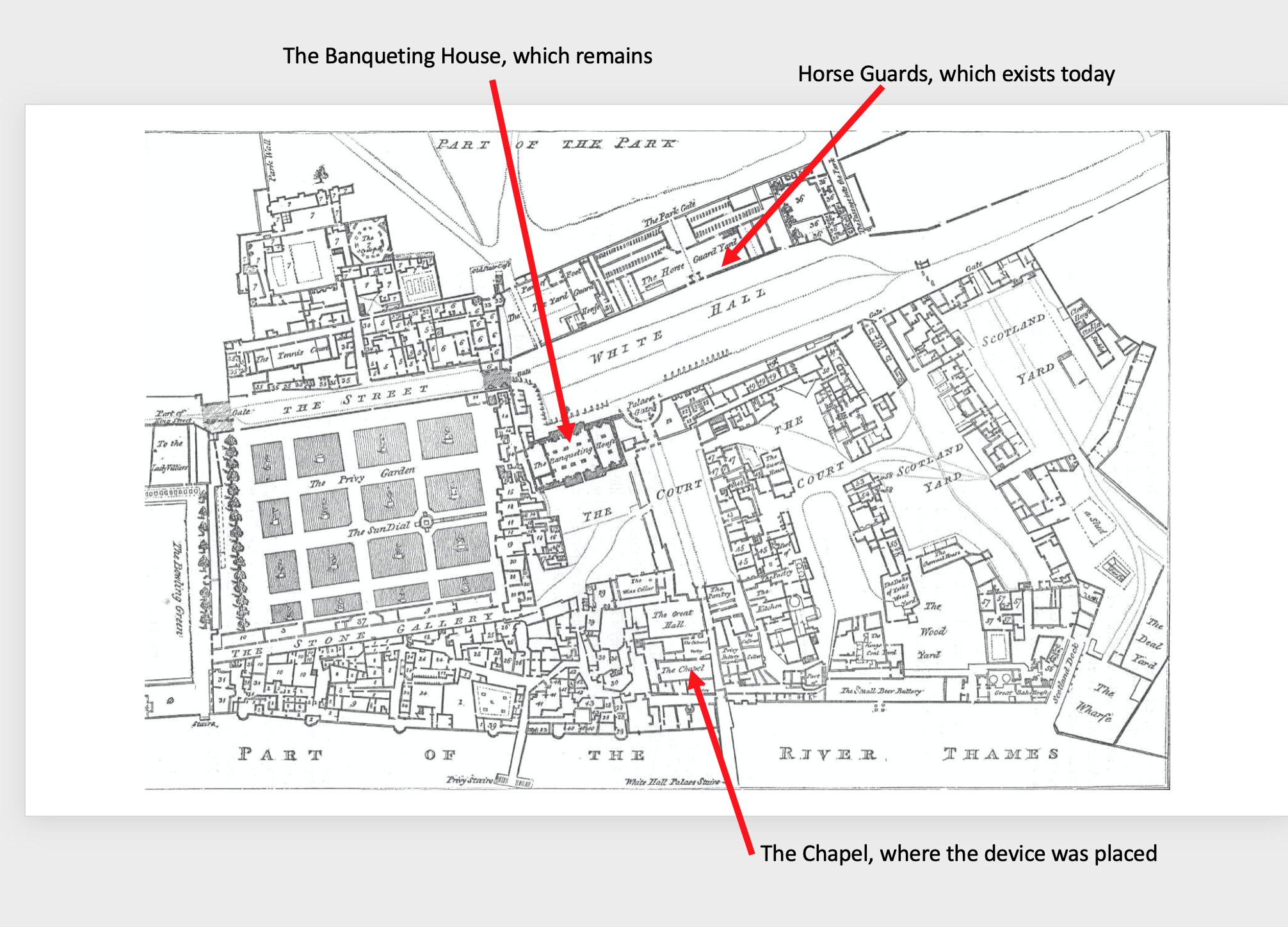

Here’s a useful pic of the Palace in 1680 – I’ve highlighted the chapel. It does indeed look like a warren of buildings. Those of you familiar with the area in modern day can orientate yourself with the Banqueting House and Horseguards