This is an interesting tale. Hold on as a guide you through it.

Admiral Thomas Cochrane, 10th Earl of Dundonald was a remarkable man. A naval hero, as a young captain he had marvelous adventures fighting the French on the high seas. The French nicknamed him “Le Loup des Mers” – the Wolf of the Seas. He is said to be, in part, an inspiration for Jack Aubrey, indeed many of the stories from Cochrane’s naval exploits are rehearsed in the novels of Patrick O’Brian.

As a young officer his career was not without aspects that cause, and caused, raised eyebrows – he was court martialled for showing disrespect to a senior lieutenant, and reprimanded. But his naval career was generally exceptional, showing daring and gallantry in action. During his time in command of HMS Speedy (with a mere 14 guns) he captured or destroyed 53 enemy ships. One of his exploits was his seizure and copying of French code books, leaving the originals behind so that the French would think they were uncompromised. When he captured the Spanish ship El Gamo, in 1801, he personally led the boarding party of 53 which consisted every man of his own ship, bar one, the surgeon, and took 319 Spaniards aboard the El Gamo prisoner. The El Gamo had seven times the firepower of the Speedy. As the hand to hand battle was being fought fiercely and in the balance, Cochrane called over to the surgeon (the sole man left behind) and called for him to send “the rest of the crew to join the fight”, so disheartening the Spanish.

After a short political career, he was convicted of stock fraud, dismissed from the Navy, lost his knighthood, humiliated in public and expelled from parliament (but then re-elected), standing on a ticket of parliamentary reform. He was eventually pardoned in 1832 after a change in government. He was restored to the Navy list in the rank of rear-admiral.

In the intervening period before he was pardoned, he continued an adventurous life. Leaving England in disgrace he became a Chilean citizen and became a Vice Admiral of the Chilean Navy, conducting spectacular naval operations from his frigate the “O’Higgins” against the Spanish.

He then left Chile in a fit of pique and enrolled in the Brazilian navy ( I said you had to hang on and I haven’t even got to the interesting bits yet!) . He took command of the Brazilian flagship and fought the Portuguese, and fought them hard. In one episode he chased the entire Portuguese fleet across the Atlantic with just one ship. He then fell out with the Brazilians and left with his pockets full….

He then joined the Greek Navy and fought the Ottoman empire, for once, with little positive effect. His wiki entry is worth a detailed read.

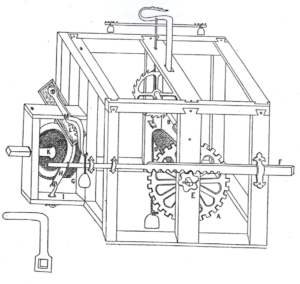

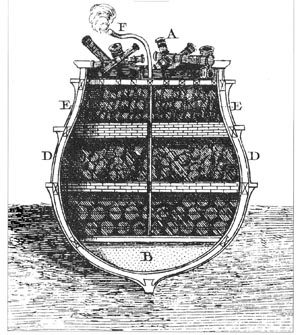

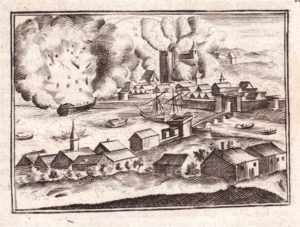

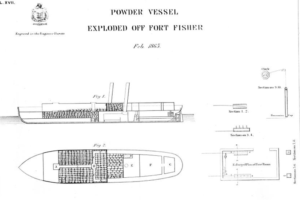

Now, my interest in Cochrane, beyond his adventures, was in the development of certain weapons technologies. He invented numerous devices and systems to aid naval warfare and in other areas too. He worked with Brunel on tunneling systems and with Stevenson on steam engines. One of his technologies was an “explosion ship” (see earlier posts). Explosion ships or “Infernals or “Machine ships” were not new but Cochrane made use of them to his own design in his attack on the French ships at Aix Roads in 1809

In 1811 he developed a mysterious weapon which became known as “Dundonald’s Destroyer”. He submitted a secret report detailing the technology in 1812 to the prince regent. This secret weapon system was demonstrated to the government on more than one occasion. On each occasion the reports are that the government reviews (whose panel included other weapons developers such as Congreve, the rocket developer) were horrified with its effectiveness but declined to acquire the weapon system, it being beyond the sensibility that any person could use it against another, or as they described it “too horrible for humanity”. They demanded that its mystery remained secret. Even 100 years later, in 1914, as Britain faced the German empire there were calls to unveil and field this mysterious system. There is a suggestion that a German butler stole the papers detailing the plans from the Cochrane family and passed them to the Germans in 1914. Cochrane described the system as follows:

“The infallible means of securing at one blow our maritime superiority and of thereafter maintaining it in perpetuity,” that “no power on earth could stand against it,” that it could be used by the weakest nation against the strongest, and that its construction was “so simple that the most ignorant minds could readily master its mechanism.”

Some historians suggested in the early 1900s that the device could have been some form of focused beam of sunlight using lenses and mirrors, which frankly I don’t find credible. Others point towards Cochrane’s experiments with “smoke ships”. Cochrane, as we know used fire ships to cause arson and panic in an opposition fleet, and machine ships to detonate amongst them. He also used smoke ships loaded with burning sulphur and charcoal which caused thick smoke that disguised the movements of his own ships. The suggestion is that he realised that the choking effect of the sulphur dioxide produced a chemical effect on those exposed to it that turned it into a chemical weapon. It seems the “Destroyer” was an improved version of the smoke ship, and perhaps associated with improved “machine ships” that exploded. There is some mention of machine ships being tilted at an angle to project massive explosive effect in a single direction being used in conjunction with hulks loaded with charcoal and sulphur.

In the Crimean War, Cochrane again proposed the use of explosion ships and ”stink vessels” against the Russians at Sebastopol and in the Baltic. The eminent scientist Michael Faraday was consulted with regard to the potential effects of the burning of 400 tons of sulphur (which gives us an indication of the scale of Cochrane’s plans), so it is clear the ideas were seriously considered some 40 years after Cochrane made the initial suggestion.

It’s apparent that “Dundonald’s Destroyer” was some form of Weapon of Mass Destruction. I note that Cochrane claims that it could be used on land or at sea…. Cochrane himself died, penniless in 1860.