I’ve been researching for this post for quite a while and of necessity it’s going to be my longest post. Ilya Starinov is arguably the most important person in the history of IEDs and in that sense he is worthy of our attention. It’s a remarkable story of a man fully across a series of technologies, skills and operational employments. Starinov was a railway engineer, a demolition sapper, a communications specialist, an EOD expert, a commando, a trainer, a weapons exploitation specialist and an extremely innovative thinker. He was also very lucky to avoid being purged by Stalin. His achievements include:

- He championed and developed the operational use of the first Radio-Controlled IEDs.

- He oversaw the most intense IED campaigns in history, and I think through those influenced the course of WW2 and revolutionary insurgencies around the world

- He developed the Soviet Spetsnaz concept

- He fought in at least three wars, developed modern partisan techniques and advised the Soviet Union and its allies – overtly and covertly – for decades.

- He carried out dozens of attacks personally, he personally built hundreds of IEDs and was responsible for the designs of tens of thousands of others.

- He trained thousands of people in the use of IEDs, developed technical capabilities that did not exist before and designed concepts of operations to make best use of the opportunities that IEDs provided to the user.

In this post I’m going to cover some of the factors in his life story that influenced him to become the person he was. His story should be more commonly known in the EOD and counter-IED community. The use of IEDs was extensive in WW2 and that’s not widely understood. Every time the modern world encounters the use of IEDs it surprises us, and it shouldn’t because IEDs are not new – this story once again reinforces that, but also perhaps shows how IEDs became embedded in modern insurgencies. When the US and its allies encountered an insurgent IED campaign in Iraq in 2003/4, the military world should have taken a sharp intake of breath and said “Ah, Starinov, what lessons from his story can we learn from to apply here?”. But no-one, not a soul, did. And that’s why this story is important.

Starinov had a very significant but broadly unrecognised influence on global IED tactics and strategies. He is not someone to ignore. As I run through his life history I’m going to highlight the key factors in bold which led to his eventual way of thinking about the use of IEDs.

Starinov was born in 1900 and died in 2000. The first thing to note, and it’s significant, is that his father was a railway worker, employed by the Russian state to maintain the railway tracks of that country. So, from his first boyhood experience he knew the importance of the railroad to a nation, its logistics and the vulnerabilities of that system. It was in his blood, and you can see that in his subsequent concepts. One of his earliest memories was of his father inspecting the railway track, finding an unattached rail and warning an approaching train by the use of “railway detonators” laid on the track to signal the driver of a fault ahead. His family were poor (like most Russians of the time) and he lived in a small village.

The next factor in his development was the Bolshevik revolution which, unsurprisingly, he participated in with enthusiasm as a youth. Although he wasn’t using explosives at this time he did participate actively at first, blocking railway lines to St Petersburg (Petrograd) with lumber to delay “counter-revolutionary” White Russian reinforcement. This experience of his youth in terms of blocking railway lines further developed his understanding of sabotage activity, and the specific places to have maximum effect. The other lessons he learned during this revolutionary period was that operating in areas controlled by the enemy was easy at night, and ambitious sabotage plans were often rewarded with dramatic results for minimal resources. He served as an infantry soldier in the Red Army and at one point in 1919 was badly injured by shrapnel. He nearly lost his leg, but recovered under treatment. During this recovery in hospital he was persuaded by fellow patients to join the “sappers”. It was as a sapper he received some on-the-job training followed by more formal education in technical matters.

For a period of time he worked with munitions, and became adept at the handling of explosives. He then attended a training course in military railroad matters, building on his expertise in this matter. The importance of the railroad in Russia should not be underestimated. In a country of the vast size of Russia and the Soviet Union, it was the only way of managing the logistics of war, and its vulnerabilities were obvious to the young Starinov. In 1922, with great pride, he became a formal member of the Communist Party and after his training became an officer in the Red Army.

By about 1923, Starinov was commanding a Unit repairing railway lines damaged in the revolutionary war. Part of his remit was dealing with unexploded ordnance adjacent to railway lines, removing them and detonating them safely. In effect, Starinov became an EOD expert. This comment from his diaries is very instructive:

I took full advantage of each piece of unexploded munitions to study the construction of the fuses. I conducted the first experiments in melting down the explosive material out of the bombs and shells, and managed to convince myself that this was a safe procedure. It was useful as well because of the great need for TNT, especially in the spring when it was necessary to break up the ice jams that threatened railway bridges.

The next paragraph in his diaries shows, I think, the direction of his thoughts perfectly

At that time (1923) I first thought about constructing a portable mine for destroying enemy trains. Our mines had to be simple, convenient, and safe; and the fuses had to work faultlessly. In the civil war we had already become acquainted with the construction of a cumbersome, complex delayed-action anti-train mine. We only ever set one of these off, but for the rest of the war we lugged around the remaining mines for no purpose. The Red Army didn’t need such awkward devices!

In 1926 Starinov was assigned a special task of advising a comprehensive defensive plan for the Ukraine. The plan was to counter any potential invasion from the west from Poland and Romania into the Soviet Union. As a railway expert to the military committee developing the defensive plan, Starinov examined the railway lines that led through the Ukraine from the Western borders, but also as a sapper he advised on a much wider range of defensive minefields and demolitions. It was at this point Starinov discovered the demolition charges in a bridge that I discussed in an earlier post. It was he who developed the render-safe technique on the spot and his EOD team that undertook the operation.

Starinov as a young man

More broadly, the defensive plan developed by the committee that Starinov worked on has modern echoes. Their plan was to fight a defensive partisan war after invasion of the Ukraine by a western aggressor. It involved preparing and maintaining explosive resources and for partisan groups to attack after the invading Western army had taken control of the country – very similar to Saddam Hussein’s strategy in Iraq in 2003 – it’s very hard not to see absolute parallels. For the Soviets, “partisan warfare” absolutely fitted their revolutionary communist idealism of a fight “of the people” against the enemy. So here we have Starinov in 1926 at the heart of planning partisan IED campaigns in the Ukraine, territories which would see that exact thing happening 15 years later in 1941. As a good communist, Starinov looked for political validation and context for his military strategies. By 1933 Starinov had a played a key role in training over 9000 people as partisans for the defensive plan for the Western Soviet Union. That’s quite a cadre. There was already, by then, a plan for hundreds and hundreds (no exaggeration) of secret explosive hides across the whole Ukraine. The entire western part of the Soviet Union was in theory ready for intense IED led partisan warfare as early as 1933. Starinov however noted that these plans were hampered severely by the the Stalinist collectivization of agriculture that occurred in parallel, and the consequent upheaval in society. But he had to hold his tongue. Furthemore when the Stalinist purges were started in about 1933/4, one of the first things they “purged” was the partisan infrastructure.

During the early 1930’s Starinov undertook more training in communications, so he became familiar with the use of radios in military environments. He was also tasked with training partisans as part of a Soviet program to sow partisan leaders both at home for defensive operations and abroad for other purposes. He trained them extensively in explosives, and associated techniques at a number of semi-secret schools. Included in his students were several Western European communists who rose to prominence later in their own countries. Starinov remained a vocal proponent of partisan warfare and the use of IEDs for the rest of his life.

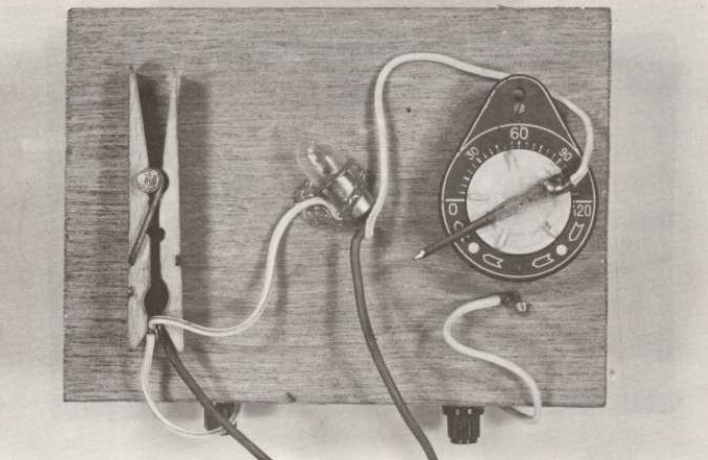

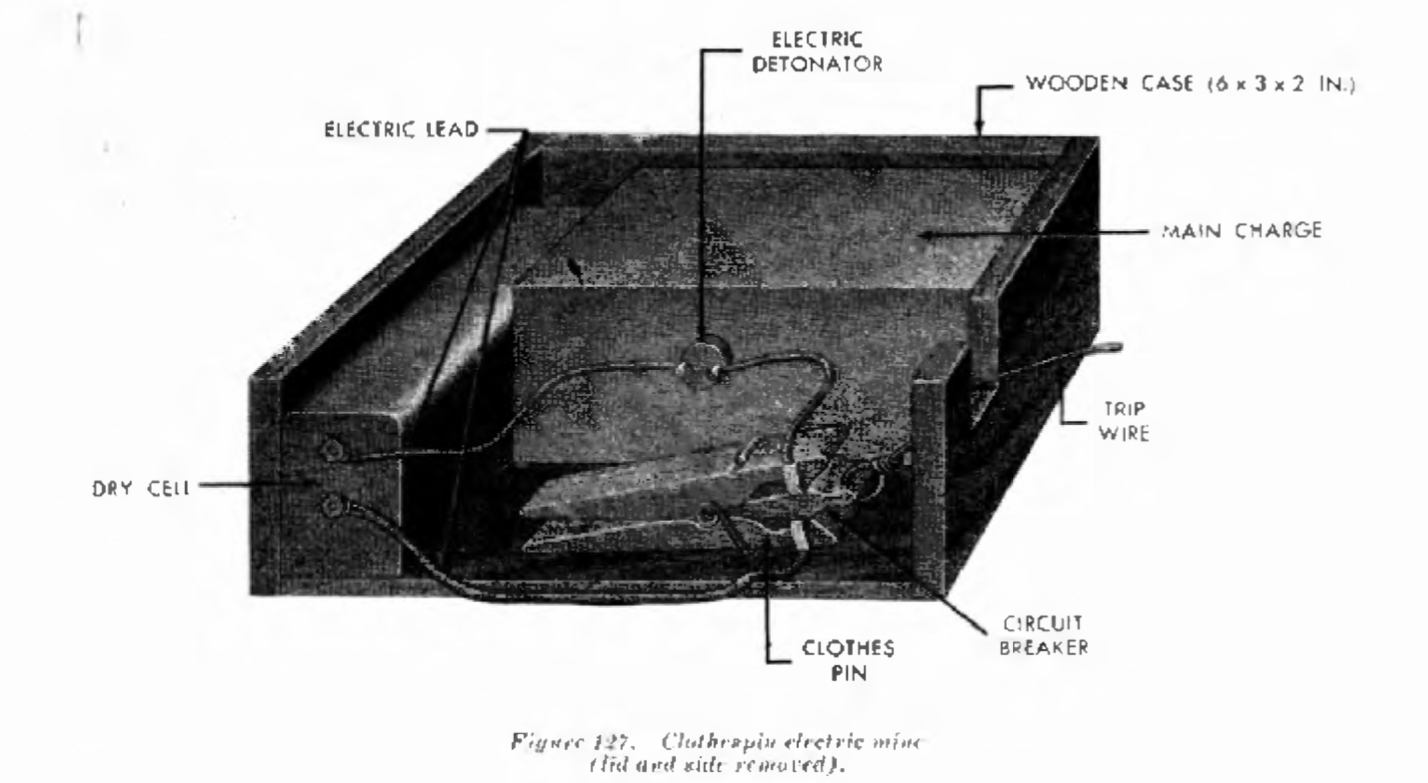

It was at this point in history that something strange but I think very significant happened which influenced Starinov to develop expertise in “improvised” explosives. We have already seen that he was not enamoured with the “production” demolition munitions used ineffectively to attack railway lines during the Russian revolution. However by the early 1930s several designs (some of them by Starinov and some be design bureaus) were ready for production. But the political landscape suddeenly changed as Stalin began his purges. It’s clear that Starinov believed that stockpiles of mass-produced, industrial-manufactured sabotage devices were not being produced because Stalin feared their misuse domestically to unseat him from power. As a result Starinov could not “teach” his classrooms full of future partisans in the use of standard manufactured Soviet sabotage munitons (which would have fitted political doctrine), so he had of necessity to teach them how to make improvised devices. One of the only exceptions appears to have been the F-10 device discussed in an earlier blog post.

It is clear that on several occasions Starinov himself was lucky to avoid Stalin’s purges. He was certainly investigated for counter-revolutionary thinking in 1935 and his party membership temporarily suspended. Some of his mentors were “purged” which usually meant arrested, tried and executed in short order.

In 1936 the Soviet Union decided to support the opponents of Franco in the Spanish Civil war – and Starinov volunteered for a secret mission to teach, and conduct, partisan activities using IEDs in Spain. Because the mission was secret, the explosive devices had to be largely improvised from locally available components and not shipped in from the Soviet Union, so Starinov’s skills were ideal for the task. Given that in 1936/37 Stalin’s purges were in full swing I sense that Starinov was glad to be out of the country, and able to employ his skills for the international cause.

At one point in Valencia, Spain, Starinov was making IEDs in his accommodation at night and he and his comrades were carrying them in disguised packages every morning to the facility where he was training Spanish communist revolutionaries. Starinov had strong reservations about the operational command and control skills of the Spanish communists, and gradually became more and more insistent that they listened to him. In his diaries he discusses some of his devices with frustratingly vague descriptions, probably for ingrained operational security reasons. Amongst his descriptions are “match box fuses” that I think were improvised initiation fuzes (pull/push and perhaps timed), and another is described as a “wheel switch” that perhaps was used in railway IEDs. I’m not quite sure what a wheel fuse was but they appear to have been smuggled in from Russia, and they were specifically manufactured as initiation switches- perhaps they were some form of microswitch. He describes some of them as being “nearly 20 years old” which is intriguing. Most importantly Starinov started to use a phrase to describe the Spanish revolutionary “commandos” who he trained and operated with, which he called the “brigade of special designation”. The phrase in Russian is “Brigad Spetsialnogo Naznacheniya” In typical Russian abbreviation this becomes “Spetsnaz”. So Starinov formed and ran the first Spetsnaz unit, conducting sabotage operations in a foreign country.

As an aside, at this point in his life, actively conducting sabotage operations using IEDs, Starinov had to square his violent activities with his politics. Here is is own justification, which is very interesting:

From the most remote times, saboteurs have been condemned as dark and violent men, with neither conscience or honor. There’s no argument that the dregs of humanity graduating from the intelligence schools of bourgeois nations are animals of this type. But in armies fighting for popular causes, demolition men become the best. most dedicated and most humane fighters.

Make of that what you will.

In Spain Starinov began to train small groups of men who would cross over secretly into enemy territory conduct sabotage operations using IEDs and operate in what today would be pretty close to Spetnaz operations. Starinov took part in several operations but also continued to develop the IEDs. He had particular challenges with dynamite which was too sensitive for convenient use, but he struggled with several attempts to de-sensitize it, usually making it too insensitive. But it demonstrates considerable innovative thought in his IED techniques and determination to operate in non-ideal conditions – key lessons were learned.

During one operation Strainov learned another key lesson. The concrete bridge they were attempting to destroy was simply too sturdily built, and Starinov realised, and was able to convince his Spanish colleagues, that using a smaller amount of explosives to attack train was likely to be a more effective operation. But of course this form of attacks requires, ideally, different initiation switches so the insurgents could depart before the train arrived.

I believe this attack was by Starinov’s unit in Spain but I cannot be certain

One device is described by Starinov (vaguely as usual) as an “ampule fused” explosive device. I believe this was a modern version of the Jacobi fuse which I have described in earlier posts. It consists of a glass ampule containing sulphuric acid which when broken reacts with potassium chlorate to detonate explosives. (I think it was used as a victim operated device, and it wasn’t like the British time delay pencils which could also be described as ampule devices but which would not have worked in this mode of employment). Starinov describes these as being laid in ruts in tracks to attack chasing enemy Spanish fascist forces.

Elsewhere he also describes electrical booby-trap switches using the action of pressure or with a tripwire. He worked extensively in a small garage workshop in the back streets of Valencia developing and making a wide range of IEDs. I doubt it would have looked very different to a modern backstreet IED workshop in Syria. Bizarrely he describes how he would rather work making IEDs rather than accompany his colleagues to watch the spectacle of the bullfight “where innocent animals were killed”.

He also learned much from failed devices, improving their design and hence consistency. In particular he found the “ampule” designs operated too slowly so he successfully redesigned “wheel switches” and “ampule fuses” to operate faster. Interestingly he also developed timed safe-to-arm circuits to make the positioning of the devices safer. The safe-to-arm timing was about ten minutes, but I have no detail on how this was achieved, but I think it was electrical. I think this was an important development and I can find no mention of a electrical safe-to-arm timing circuit in an IED in history before this. At one point Starinov complains that the macho Spanish emplacers were not bothering to use the safe-to-arm circuit, so he redesigned the whole system circuitry so they had no choice.

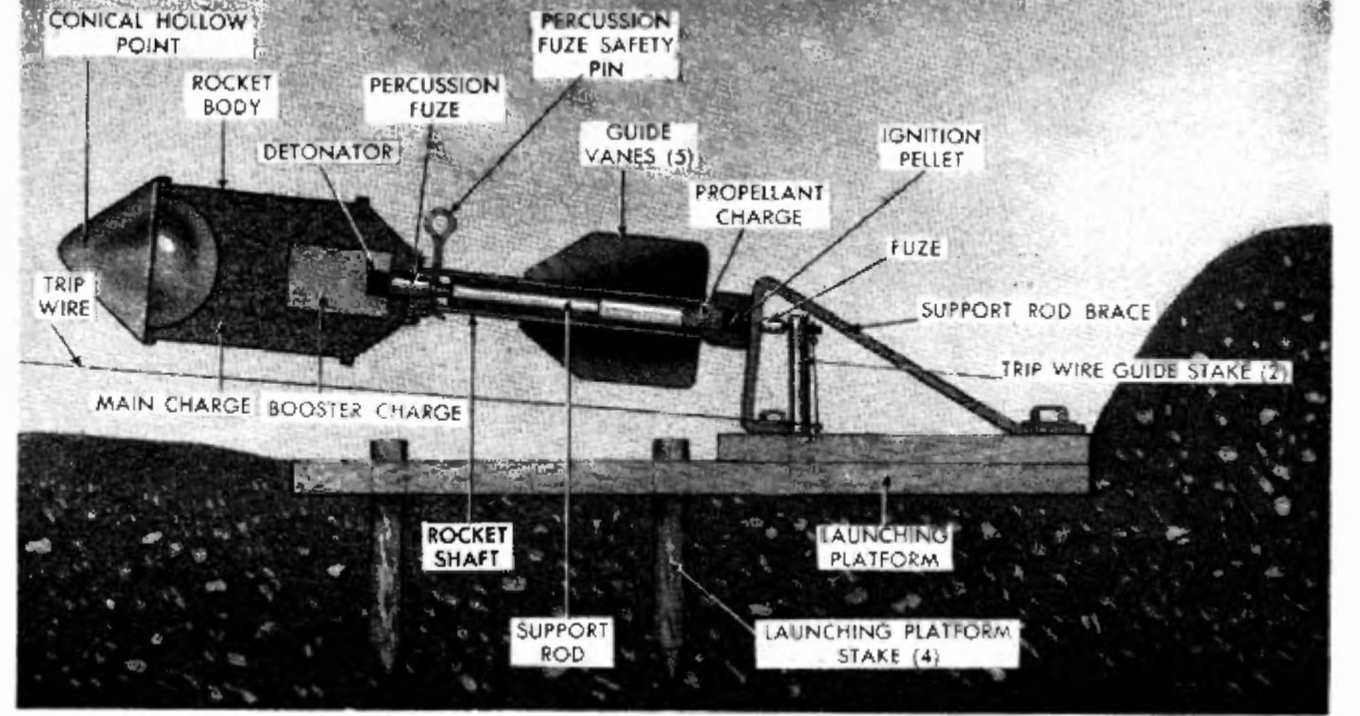

Starinov’s IED innovation seems to have been endless. He designed a special IED that could be emplaced between the rails at speed (less than a minute), designed to explode before the train wheels arrived at that point and so derail the train. They contained only 1.5kg of explosives so were more efficient in terms of explosive utilisation than a large charge set to explode under a train. These were called “rapidas” mines because they could be set so quickly.

At one point Sarinov was unhappy with the sensitivity of dynamite still. So he obtained a number of massive depth charges from the Navy and in the garage workshop in Valencia melted out two tons of TNT for his devices. He also adapted pocket watches as timing devices, and made improvised grenades. One particular attack is worthy of note. Starinov’s team had identified a munitions train and a tunnel, through which the train would pass. Starinov built what he called a “pick up” mine. As the train entered the tunnel a hidden hook system of some sort caused the train to “pick up” the explosive device which contained 50kg of explosives. Now attached to the train the device functioned a few seconds later in the centre of the tunnel, destroying the tunnel and all the munitions on the train at once. Interestingly Starinov describes this device as having been originally developed in Kiev in 1932.

In the spring of 1937, IED attacks on trains and vehicles became an almost daily occurrence. The counter-measures, patrols and search techniques used by the opposition encouraged Starinov to develop anti-handling devices for when the IEDs were discovered. They also developed anti-train IEDs with long delays that could be planted on moonless nights but would activate and detonate as a train passed over a couple of weeks later. Other magnetic IEDs were developed which could be slapped on a target. One particular attack is worthy of attention, although Starinov reports it, he may have not had any direct role. The monastery of La Virgen de la Cabeza was occupied by fascist forces in April 1937. One week a passing itinerant mule-rider came under fire from the monastery. He abandoned his mule which was then taken into the monastery. This was noticed and the event exploited by the besiegers, who caused it to happen again 10 days later. This time the “Trojan” mule was carrying a large IED containing 20kg of dynamite on a timer… and it detonated inside the gate as intended.

Starinov eventually left Spain in the autumn of 1937 – with a strong conviction that his explosive successes were built on the preparatory work done in the Soviet Union in the early 30’s. Little did he know that he would fold back his Spanish experiences into identical activity against the Germans some four years later. Take this important assessment that he made:

In Spain, the tactics and techniques of mining worked out by Soviet-led partisans were more sophisticated than those employed by the enemy for minesweeping. The enemy could not guarantee the security of their rear area. They never did learn how to find several types of our mines, and those they did find, they could not disarm except by exploding them. German and Italian sappers (operating to assist Franco’s forces) tried to learn about our equipment but we constantly gave them new puzzles to work on. Sometimes we set booby traps for them, or fitted mines with fuses that couldn’t be removed or used magnetic mines which were unfamiliar to the enemy.

In the ten month period he was in Spain, between December 1936 and September 1937, the unit which Starinov was attached to and for whom he made his IEDs carried out 239 sabotage operations, 17 ambushes, derailed 87 trains, destroyed 112 vehicles and killed 2,300 enemy. His unit lost 14 members. He also trained hundreds of Spanish and international partisans.

Starinov returned to Russia and found the place fearful of the purges – many of his former colleagues and commanders had been arrested and executed. Alongside them, many of the partisans he had trained were also purged. He was extremely uncomfortable, but there was nothing he could do other than hope he wouldn’t be purged himself. He was interrogated at the Lyubyanka and only then realised that all his efforts to set up a defensive partisan capability and weapons caches along the Soviet Union’s Western border had been liquidated and cancelled, out of the paranoid fear that drove the Great Terror – Stalin felt threatened by such an underground capability. Starinov was shocked.

Importantly though, Starinov was promoted to Colonel and given responsibility for managing a military test range. His resources included an experimental workshop, an 18km railway and a company of demolition troops. He set to work developing new methods of destroying and repairing railways lines and developing explosive devices for a variety of special purposes. Amidst the chaos of the Great Terror of Stalin’s purges this was the perfect employment for him. He also developed counter-counter-mine technology at increasingly high levels of sophistication. This included the development of special augers that would bury explosives deep, beyond detection or plough capabilities. He wrote a dissertation called “On Mining Railroads” on explosive methods of putting railroads “out of action” for at least six months but with specialised equipment could be repaired much more quickly if the territory was recaptured from an enemy.

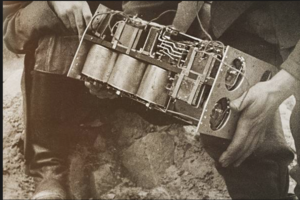

In November 1939 Starinov was posted to command an EOD unit supporting the Russian invasion of Finland. What is very significant here is the process of Weapons Technical Intelligence conducted by Starinov and his team on the Finnish mines, which he assessed as extremely complex. This technical exploitation was conducted rapidly in the field on recovered devices. The first step was to melt out the compressed TNT in the mine, in a variety of captured Finnish cooking pots and a captured bath tub – no kidding. Within 24 hours Starinov had written up his exploitation report on the “boiled” mines and instructions on disarming them for future EOD operations. During this period, on occasion Starinov ended up defusing mines, along with his professor from the test range. He wasn’t the sort of man to hang back… He was eventually shot in the arm by a Finnish sniper, and left the Front to recover. While recovering he was assigned to be Chief of Mine and Barrier training at Military Engineering Headquarters. Again a perfect posting for him. Starinov saw his role in the job as bringing up the Red Army’s mine clearance capability to international standards.

On 22nd June 1941, Operation Barbarossa started and the Germans turned on their allies, the Soviets, and invaded. Starinov was in Minsk to start with and quickly returned to Moscow. He was given the task of defensive demolition on the strategic route to Moscow, but frankly struggled due to a lack of appropriate munitions and materiel. All his efforts from 1926 to 1934 had been squandered. He was given command of a weakened brigade of sappers, and the only digging equipment they had was spades. There was one rifle for every 3 soldiers under his command.

Starinov headed for the front to begin preparing bridges for demolition – but he found the NKVD had been given responsibility for the bridges and had not been informed of his engineering mission – they arrested him for a few hours as a saboteur. Such were the challenges of a dysfunctional Russian military at this time. Afterwards he led his sappers in conducting a series of demolitions in support of the retreat, and he was able to begin to return to his instinctive choice of enabling partisan IED operations behind enemy lines. The shortage of military demolition explosives also meant that Starinov reverted again to his instincts of making IEDs, but there were other reasons behind this too. As an example, the standard Russian production anti-tank mine was simply not big enough – it might break a German tank track but little more – so Starinov’s sappers, under his guidance, improvised much larger charges to go alongside the mine, or replaced them completely with IEDs. More importantly, Starinov got momentum politically to start training partisans again, by setting up a training school in Belorussia – all using improvised explosives. He was frustrated about a lack of time and resources but in his mind it was a hugely positive step. At this point Starinov was using Ammonium Nitrate fertiliser mixed with Aluminium powder, as a main charge for his IEDs and personally teaching lessons on its manufacture and use to the partisans. He commandeered material from farms from factories and from pharmacies.

Soviet partisans laying explosive devices.

At this point the political pendulum swung. Since about 1934 the NKVD, Stalin’s Secret Police had been an obstacle for Starinov as they dismantled the partisan program he had worked so hard on, and they led the purges of Stalin’s Great Terror. Suddenly in 1941, with the Germans invading, Stalin himself called for partisan action, and the NKVD switched, of course instantly, in their attitude. Starinov was a pragmatist and saw an opportunity – and he simply co-opted the NKVD into his partisan program, demanding they assist and join his sappers and swing their considerable influence over resources to help him.

As the Germans advanced through the Ukraine, more and more partisans were trained, equipped with IEDs or with ability to manufacture their own, and they slipped behind enemy lines to begin classic partisan warfare. Meanwhile the Red Army, in increasingly frantic efforts, used explosives to attempt the slow the advance.

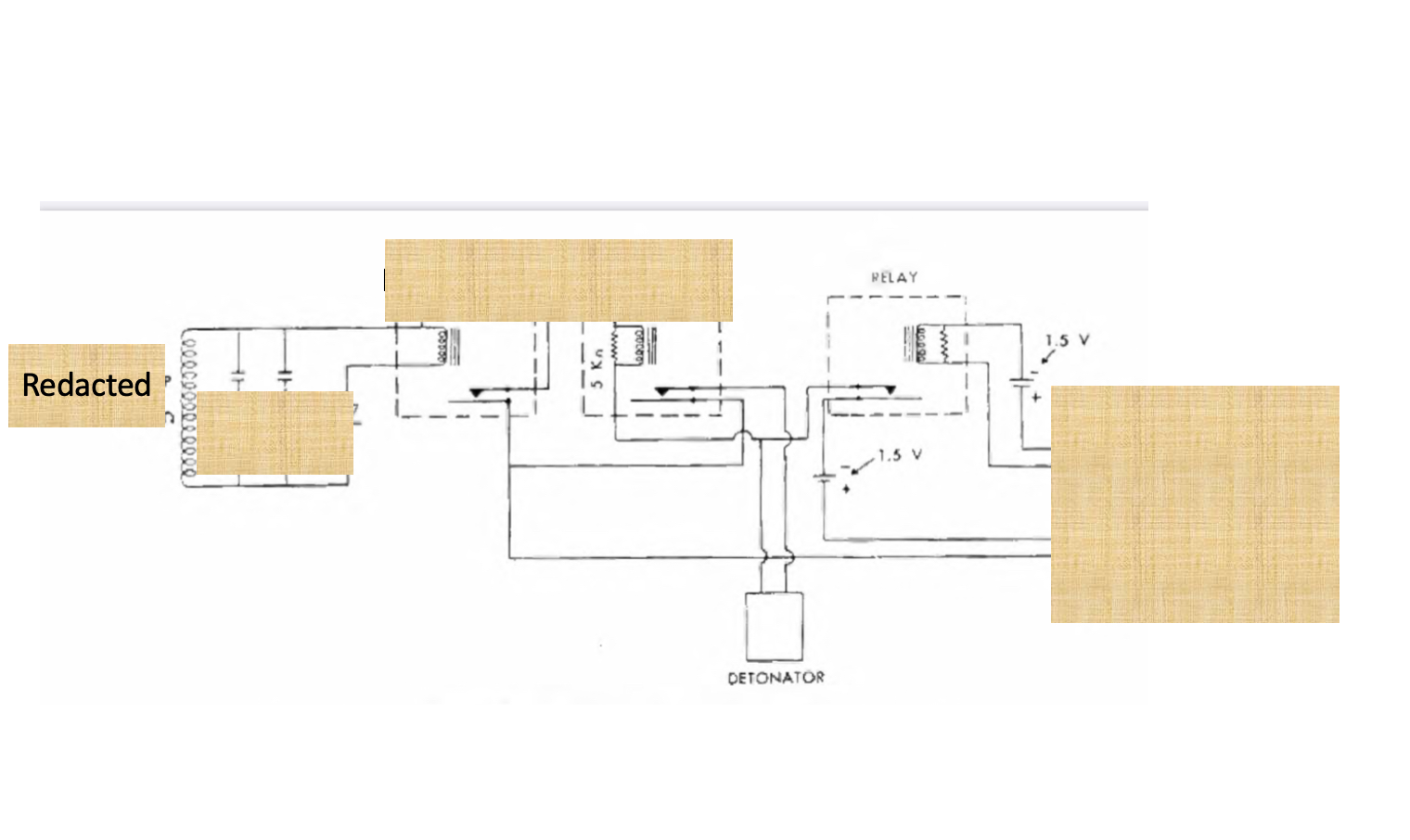

Here our story meets my earlier post about the F-10 radio controlled devices. In October 1941 the focus of the Germans was the capture of Kharkhov, Russia’s second city. Starinov led a truly massive effort to booby trap the entire city with literally hundreds of IEDs – booby traps, long time delayed devices of a month or so, dummy deception devices to slow the German advance through the city and a small number of very large F-10 radio controlled devices. Starinov himself led a six man engineer team to carefully emplace and disguise a 350kg F-10 device, dug in 2m below the cellar of the local Communist Party Headquarters at 17 Dzerzhinsky St in Kharkhov, a grand building which the Russians hoped would be requisitioned by the Germans for its military headquarters. With great care they disguised the F-10 device deep, hid its 30m long antenna, re-laid the basement floor, repainted the walls and laid another large device in the cellar in the full expectation that it would be spotted and disarmed, but act as a distraction.

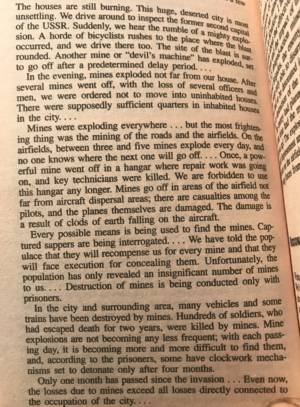

On the night of 13 November some three weeks later, the transmitter was set up 300km away in Voronezh to send the activation signal. As we know, the explosion was a success and the German General Braun was killed along with many members of his staff – but the Russians didn’t find this out for certain until 1943. However the broader activity of explosive devices laid across the City was remarkably successful and stunned the Germans. Here’s an excerpt from the diary of a German officer, describing the impact of Starinov’s IEDs in and around this large city:

It reminds me of much more recent reports about towns filled with ISIS IEDs in Iraq and Syria….

Of the 315 delayed action mines laid by Starinov’s sappers in Kharkhov, the German engineers were only able to find 37. Of these, a mere 14 were defused, the rest were blown in place.

Starinov’s next mission was to defend Moscow, and he was actively involved in that planning and encouraging the laying of tens of thousands of mines and other explosive devices. A single Russian engineer group, just one of a number, laid 52,000 anti tank mines in the ground around Moscow, and then when it snowed to several feet in depth, they laid more mines in the snow. It was a remarkable effort.

Starinov continued to push for greater use of partisan IED attacks in December 1941, getting inevitably bogged down in Communist Party machinations and policy development by people (including Stalin) who did not understand his concepts. Even making suggestions that wouldn’t go down well with Stalin or one of his immediate supporters was a life risking effort. This quote stands out from one of his submissions:

“A tank battalion is a terrible force on the battlefield, but when it is on a troop train it is completely defenseless and can be destoyed by two or three partisan saboteurs”

Starinov was then posted to develop the anti-tank defences around Rostov on Don. Finding the Red Army there very short indeed of manufactured anti-tank mines, he did what we now expect of Starinov. He designed and had built in local workshops tens of thousands of his own anti-tank mines.

In the summer of 1942, Starinov’s constant imploring to resource partisan sabotage operations finally got traction and furthermore he was appointed to the staff of the Partisan Movement, allowing him to directly influence and develop his pet strategic projects. He became responsible for a new partisan training school and also for developing appropriate technology. In this latter role, Starinov continued to innovate, including, for example the development of cone shaped charges for anti-train operations, although I’m not entirely clear how this was used. His staff also experimented with detonation systems and experimented with anti-materiel rifles against trains. In particular they experimented to develop the most efficient use of explosives to damage trains with the smallest quantity of explosives. They also further developed the “rapida” mines first used in Spain, and more importantly came up with concepts of operation for using multiple IEDs of various sorts and delays, in a mix to further hamper enemy rail activity. Starinov also thought deeply about the operational level plans and the structure , communications and strategies to be used by partisan groups.

In March 1943, Starinov was posted again, this time directly to the Ukrainian Partisan command of the Southern Front. His mission was to cut the German supply lines that crossed the Ukraine. He established a sabotage department in the Staff Headquarters. In April 1943, Starinov was directly involved a a massive coordinated sabotage operation – code named “RAIL WAR” intended to overwhelm the Ukrianinain railway system in a tremendous number of simultaneous attacks on rails using explosive devices. Starinov was unhappy with this as he would have preferred to attack the trains themselves and felt he had the technology to do that which was going to be wasted. But orders were orders. The intent was for partisans to destroy a huge number of individual rails – 85,000 in one month long period. In the end Krushchev quietly gave alternate instructions after it was pointed out that 85,000 rails was only 2% of the Ukrainian national infrastructure. In the last 6 months of 1943, Ukrainian partisans destroyed a very remarkable 3,143 trains. Let that sink in. In a six month period, Starinov’s devices destroyed well over 3000 trains in the Ukraine. Amazing.

In September 1943 another massive series of attacks on Railway lines was planned, – this one called operation CONCERTO. Many of the Ukrainian partisans utilised Starinov’s occnept of a complex explosive attack using a number of IEDs and mines of different types. By this time the partisans where well equipped and manned with about 200,000 personnel. Starinov’s pet project was finally working.

Strarinov later assisted in the training of Polish partisans and after the war was involved in EOD duties. Allegedly he taught the KGB and GRU about explosive devices for many years later, and was often an adviser to the Russian government regarding the IED threat from Chechnya. He died at the age of 100 in 2000.

So, Starinov’s importance in the history of IEDs is clear. He probably designed more IEDs, made more IEDs, and trained more IED makers than any other person in history. The lessons he learned in his remarkable life, and how he then deployed his expertise are very instructive. He wasn’t the first to combine partisan style operations with IED usage, but he certainly had the most impact.

Starinov in Retirement