It’s been a while since my last post – other things have had my attention. A reader, John C, responded to a post I wrote last year with some thoughts and this encouraged me to look again at this fascinating and crucially important piece of (explosive) history.

This then is a follow up to this post which I suggest you read through to refresh your memory. In it I explore some interesting technological developments regarding the development of explosive initiators in the early 1500s. Why is this important?

-

- Until the early 1500s, explosives (gunpowder) could only be initiated by the physical application of fire. Gunpowder was initiated by applying a burning match to a small quantity of gunpowder which then ignited a larger charge, whether that be inside a gun or inside a larger container.

- Effectively this limited the use of explosives/gunpowder, because a prior step was needed to ignite a match and keep it burning until such time as it could be used. This limited how explosive devices or firearms could be used, slowing the process or making it more obvious. So the technology development described below allows for speed of action, timeliness and concealment – all important characteristics of explosive devices.

- The invention of a mechanical igniter gave much more flexibility and did away with the need for a burning match. Devices could be placed, concealed and left. Firearms could be concealed. Devices or firearms could also be initiated almost exactly when needed rather than after a delay.

- Mechanical igniters such as this enabled booby traps (Victim operated devices) (perhaps with a trip wire), enabled command operated explosive devices (via a pull string) and even enabled timed explosive devices (where a clock hand could pull a string). As far as firearms are concerned the jump from matchlock to wheel-lock is a very significant technological leap.

So in the history of firearms and in the linked history of explosives (as the site purports to be, in a sense) these mechanical devices described in my earlier post are quite significant.

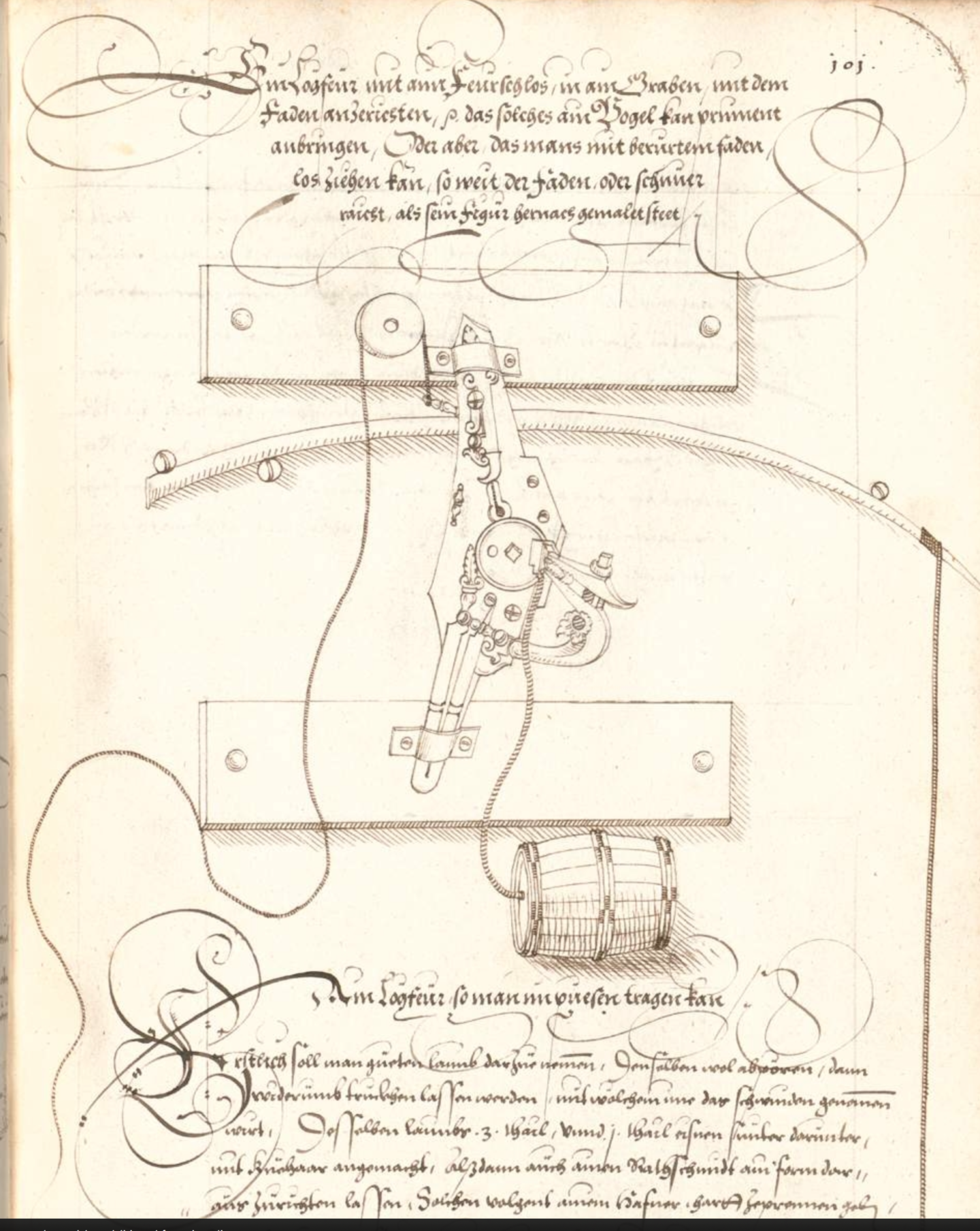

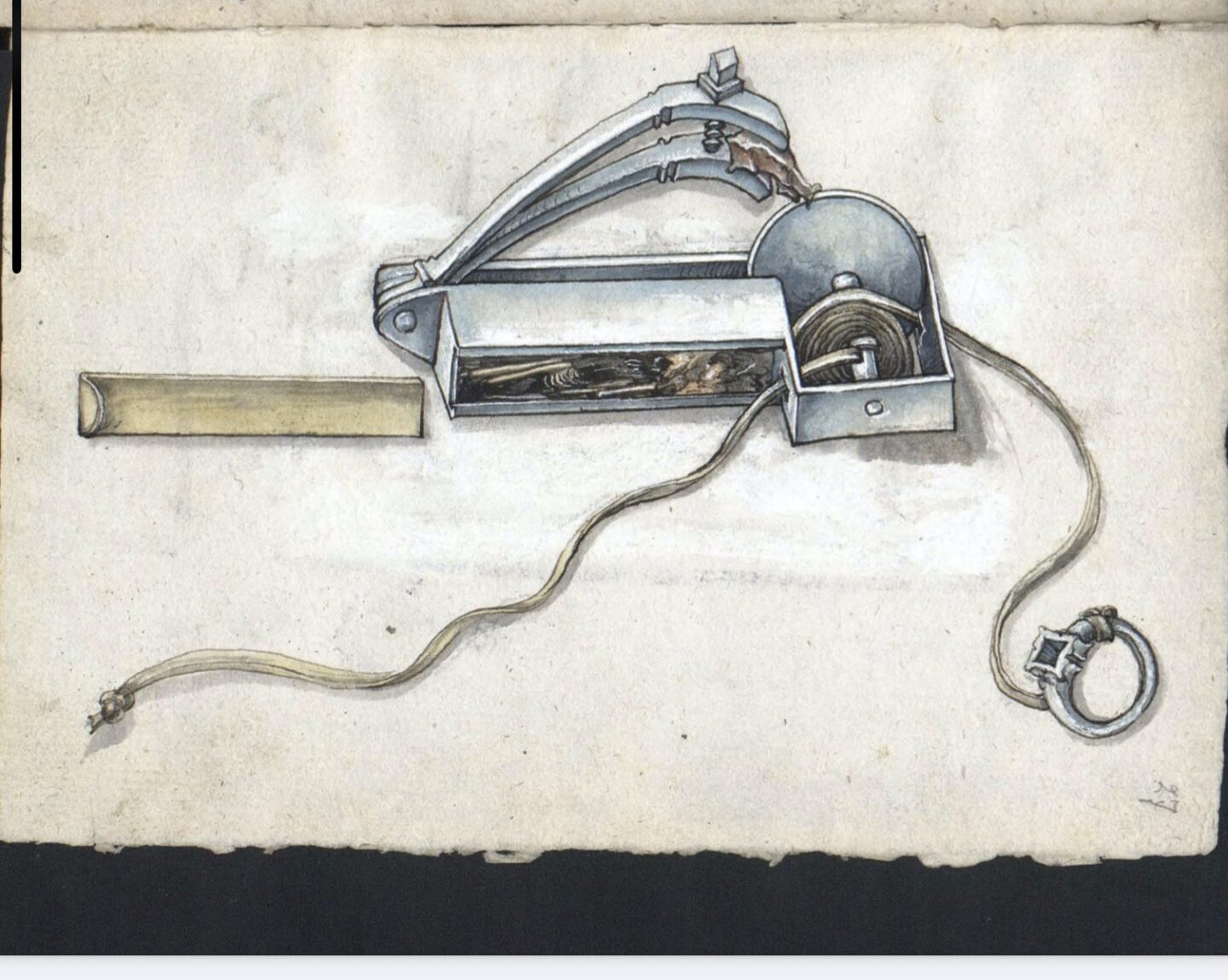

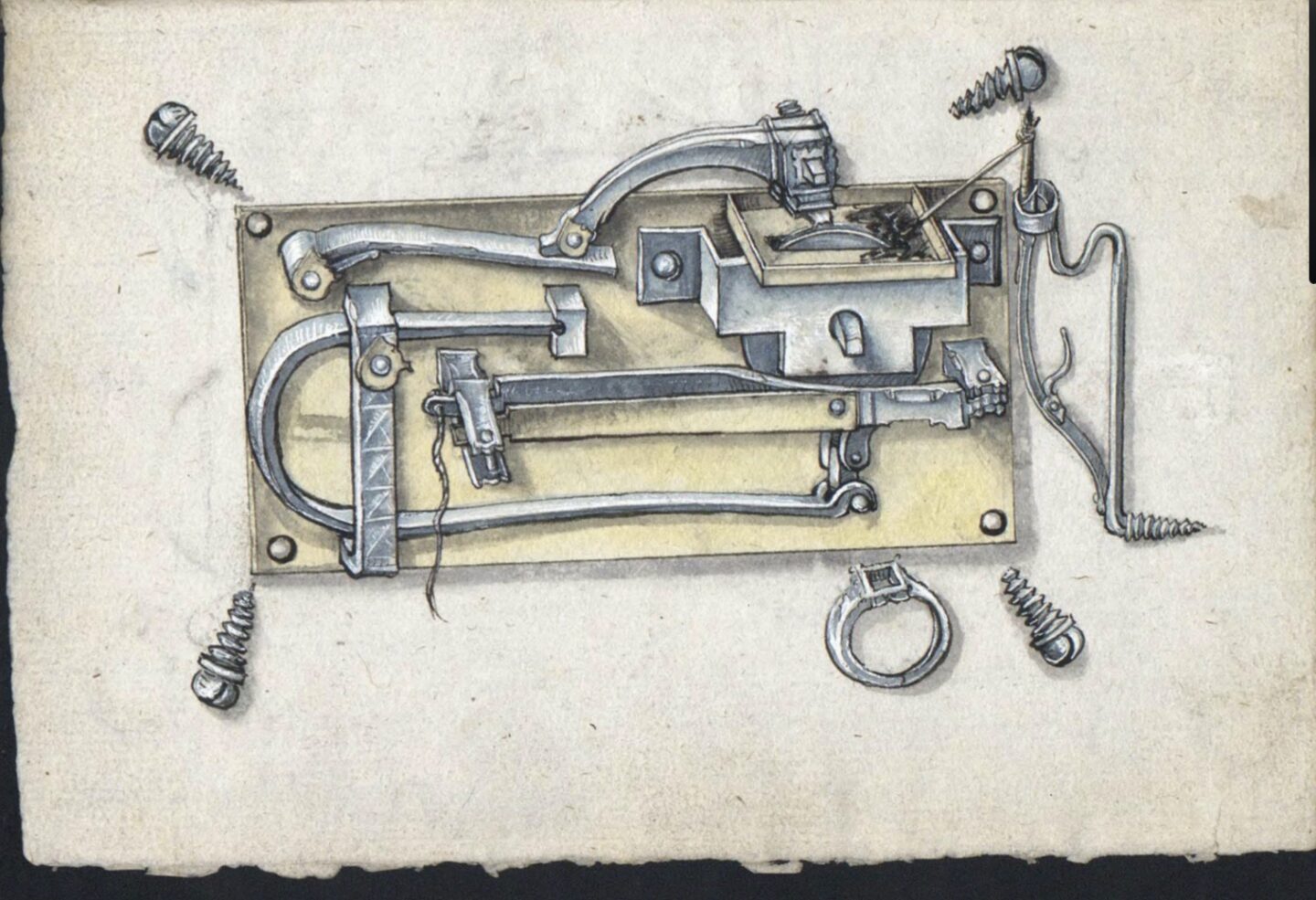

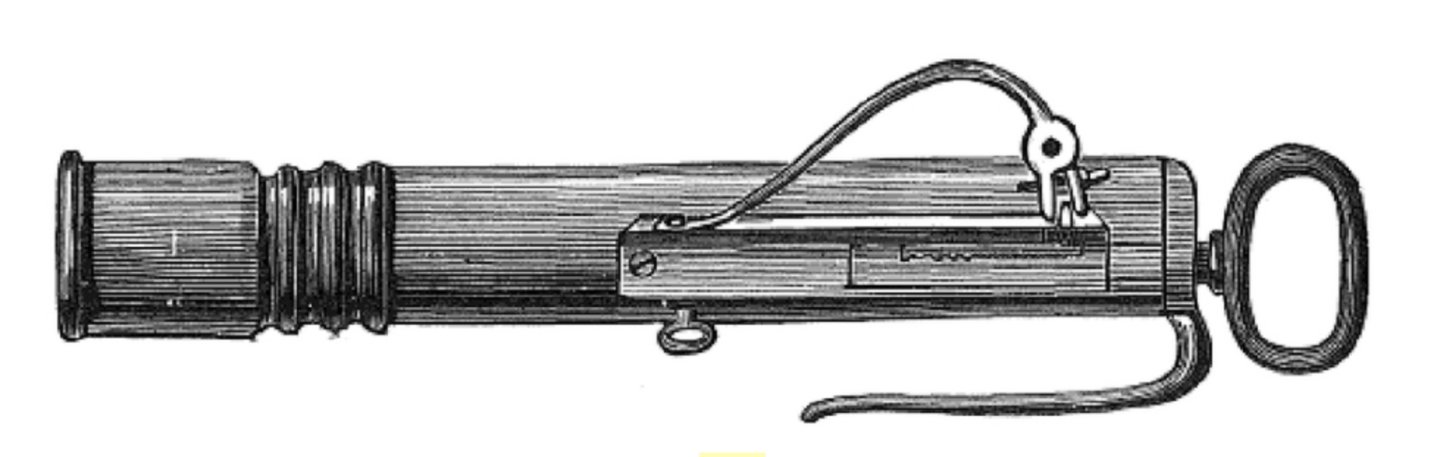

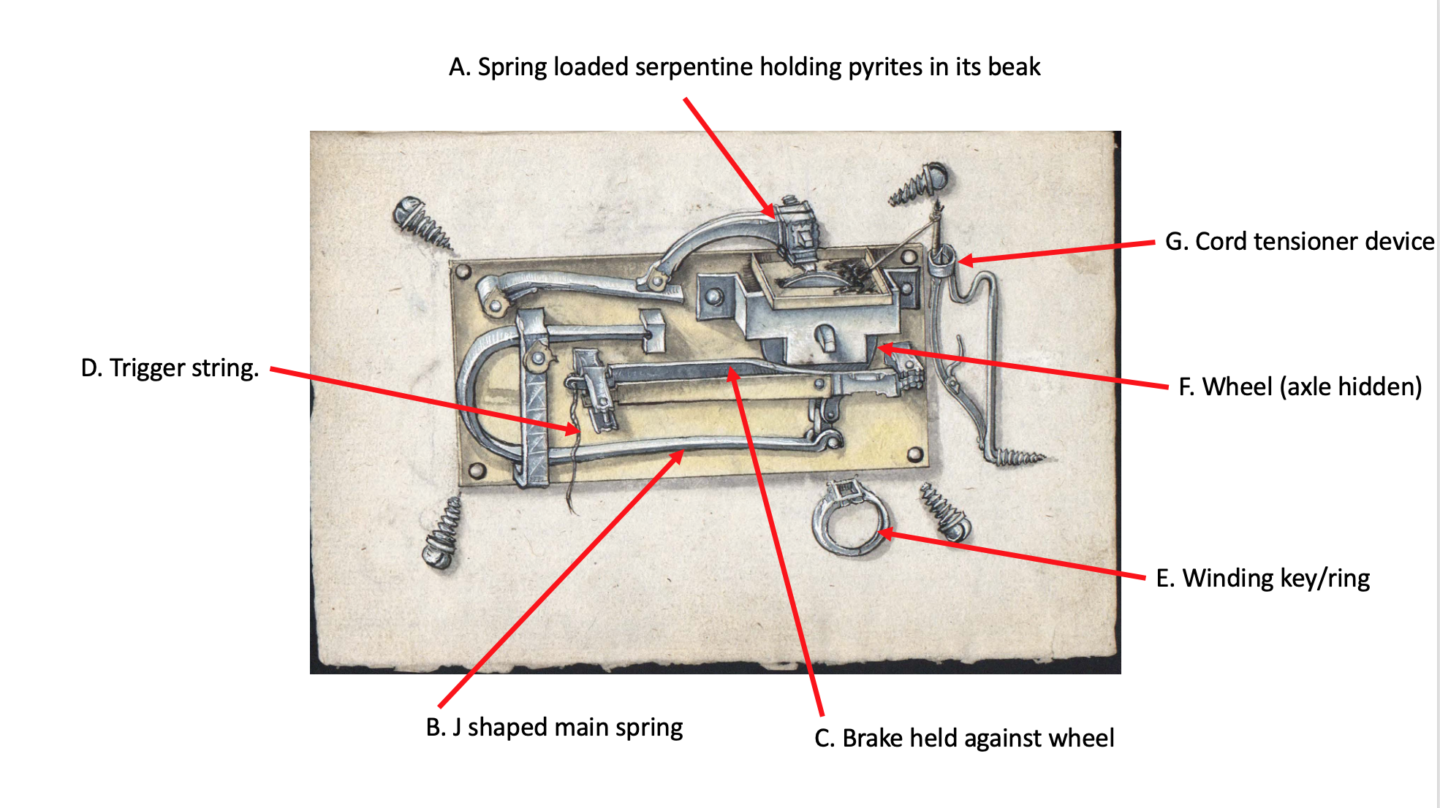

In the earlier post last year I included a copy of beautiful diagram of a mechanical igniter from a date of about 1505. Historically speaking this is technically a wheel lock but I think was invented before a similar device was fitted to a hand held firearm. It’s maybe the first wheel lock mechanism. This device and one or two others were carefully drawn and included in the“Loffelholz Kodex”. At the time I hadn’t worked out how this igniter had functioned. I’ve now spent some time scratching my head and doing a little research and I think I may have an answer. But I’m only about 60% certain, so if you think I’m wrong, please correct me. I’m very open to alternative interpretations of this intriguing machine. For ease of explanation I have included the diagram again here below but with some annotations.

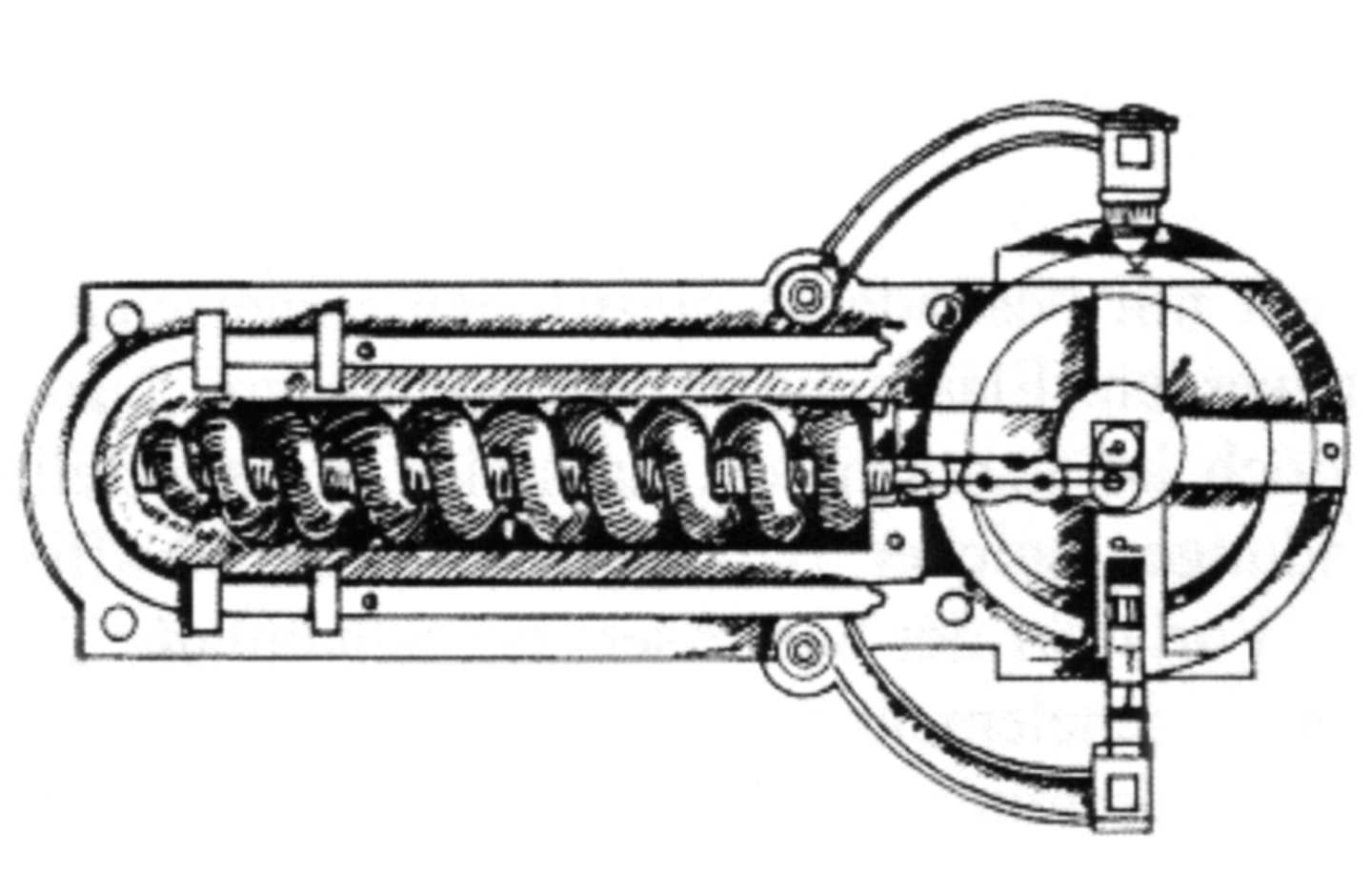

I originally thought the device had a coiled spring hidden behind the wheel (F) to cause it to turn, but I no longer think that is true. Importantly I don’t think coiled springs of the type I had envisioned had been invented at this time. Rather, like the simpler device seen in the last post, there is a cord wrapped around the wheel’s axle. The horizontal J shaped main spring (B) has its longest arm, along the bottom and this is the spring which pulls the cord down, causing the wheel to spin. The wheel is prevented from turning by the Brake (C) in the middle to which a pull string is attached. Pulling that away from the wheel is like releasing a parking brake. In normal conditions this Brake (C) is held in place by the brass bar running in parallel to it acting as a spring. The bit I’m slightly unsure of is the Cord tensioner (G). This holds the cord tight against the axle. You can see the finger holder that you pull when winding up the wheel(F) with the winding key (E).

So… let me describe the preparation and action…

1. The winding cord is tied to the end of the J shaped main spring and the other end to to the right hand contraption. The right hand contraption is tensioned using the finger guard to pull the cord.

2. The wheel is turned using the “ring key”. This causes the cord to wrap around the axle of the wheel. (Somehow!)

3. As this is done the J spring is flexed upwards, and held there by the cord.

4. The “brake” acting on the wheel prevents the tension of the cord to act on the wheel. .

5. After a few turns the brake is engaged, holding the wheel.

6. The tray is primed with gunpowder or tinder.

The action on firing is as follows:

1. At the chosen time the string is pulled.

2. This pulls the brake away from the wheel.

3. The J spring now acts pulling the cord down that is wrapped around the wheel’s axle.

4. The wheel rotates

5. The serpentine holds the pyrites against the rotating wheel

6. Sparks are generated and thrown into the gunpowder/tinder in the tray. The ignition of this gunpowder or tinder can then be used to ignite the main charge though some sort of channel.

I’m not quite sure about how the cord is wrapped on the axle – this important component is hidden from view.

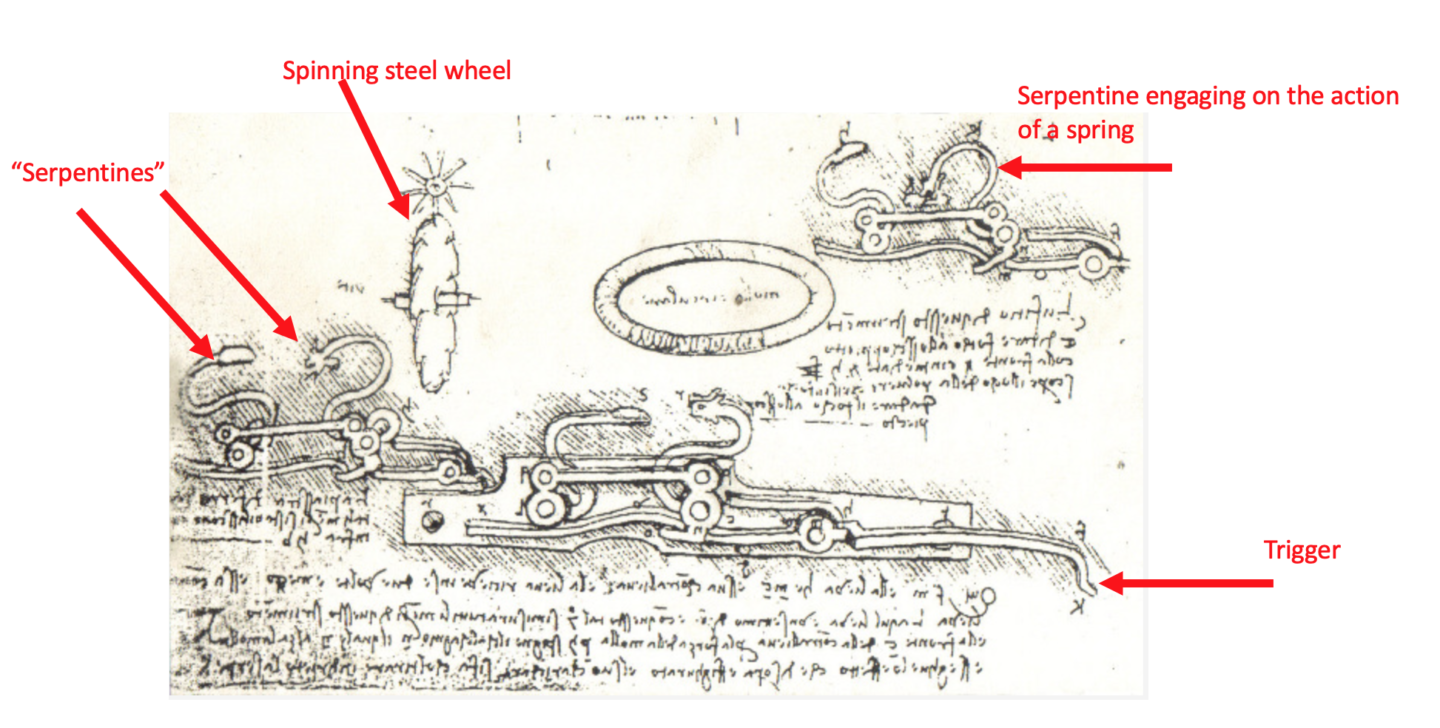

The Loffelholz Codex was produced at roughly the same time as Leonardo da Vinci was also developing spring powered wheel locks. Frankly his diagrams are much harder to interpret that these in the Loffelholz. I have no idea which came first, and it doesn’t really matter perhaps. Other technologies which enabled this design include:

-

- Metallurgy and the ability to produce, shape and utilise Spring steel, which seems to have occurred in the late 1400s.

- Clock technology, and associate manufacture of relatively carefully produced metal components.

The impact of this development was significant – in 1512 such mechanisms were banned in at least one European country because of the capabilities it provides to those with nefarious intent, and therefore a threat to society of the time. There are interesting parallels with trying to control and constrain explosive technology today. Wheel locks continued to evolve into neater, smaller designs designed to be mounted on or built in to firearms, usually with some clever spring design – but this early example is entirely separate from a firearm in this form.