Sometimes doing historical research on IEDs, you get stuck finding out technical detail and the post dies. Just occasionally the subject matter is really interesting and deserves telling anyway – but with some caveats. This is one such incident but there’s a fair bit of speculation from me on some technical matters. I’m very happy (as always) to be corrected, and happy if more technical details surrounding this incident come out – and then I’ll update. I’m very grateful for Norman B and Ian J for their valuable inputs on technical matters – there’s no-one who knows more about explosive devices of this time than these two gentlemen.

I’ve written before about a fascinating historical trend of ship-borne IEDs used in ports on the Northern coast of Europe since the 1580’s – follow the link in the connections on the right hands side of the page to ship-borne IEDs. One I have mentioned, if only in passing, was the most recent – The St Nazaire Raid – Operation Chariot – that took place in 1942. This is an interesting story and if some of the details are a little grey, then that’s the way it is.

If you don’t know the story of “the greatest raid” you should google it and get your head around this audacious operation – designed to prevent the Tirpitz from using the Atlantic, by taking out the huge “Normandie” dry dock in the German-held port of St Nazaire. The characters involved all have individual tales that are quite remarkable, but this is a blog about explosive devices, so I’m going to concentrate on that. The crucial part of that raid was a large IED hidden deep within the hull of “HMS Campbeltown” which literally was rammed into the gates of the huge dry dock at the St Nazaire Naval Base.

Once the ship was lodged in the gates, the stern of the ship was flooded to prevent the Germans perhaps pulling the ship out from the gates, and so the stern was stuck and the ship, for the time being, was going nowhere. The occupants of the ship either died in the approach action or fought their way ashore, many of them with missions to blow-up the dry dock infrastructure. Unknown to the German forces though, the fuzes in the ship had been set, and in a few hours the explosive device would indeed detonate to destroy the dry dock gates. So let’s explore what that device consisted of, and here are the caveats:

- We can’t be sure exactly how the device was fuzed, because the man who perhaps designed it and who set the fuzes died. Or alternatively the secrecy procedures of the time simply kept it all under wraps and it wasn’t discussed and recorded as we’d hope.

- Most of my sources, at this stage are not primary sources, so I’m left scrabbling for odd unreferenced mentions relating to the device that I can’t fully confirm. These are open to interpretive filters by those “swinging the lamp”.

- Some of the limited technical details about the device and its components vary between sources.

- Even if I had all the facts of the device design some of the reasoning behind the design is going to be open to interpretation anyway.

So, despite all that, here’s what I think may have been the idea. I suspect the design of the device was a collaborative affair. Lt Nigel Tibbits DSC RN was the naval officer detailed by the captain to oversee it, and he probably had the key role in deciding where the main charge was placed, and the concept of its use. I’m unsure as to his level of expertise – some sources describe him as an explosives expert and others that he was the ship’s navigator. I think he was maybe unlikely to be both. I suspect he had some form of assistance from two Royal Engineer demolition officers who are vaguely referenced, and also I suspect, from the SOE, who provided, perhaps/maybe/probably, some of the fuzes and possibly some ideas regarding concealment of the components. The device itself seems to have some of the characteristic fingerprints of an SOE sabotage device in terms of its components and its concealment. I suspect Tibbits came up with the idea of placing the device in the fuel tank, and the demolitions officers placed the charges and initiation system, and the SOE may have provided advice on concealing the initiation system and provided some key components.

Lt Tibbits DSC RN

The main charge was to consist of 24 Mk VII depth charges, each containing 132Kg of Amatol, giving a total of over 3000 kg. Amatol was a commonly used explosive in the first part of WW2, and in crude terms was a mix of TNT and Ammonium Nitrate. It’s a reasonably stable, quite effective, explosive, better than straight TNT because the “oxygen deficiency” of TNT is made up with Oxygen ions in the Ammonium Nitrate.

To give you an idea of scale, here’s a single Mk VII depth charge being lifted:

The remainder of the explosive components used were from a stock probably delivered to the ship before the operation, I think from the SOE and detailed in one report as follows:

- 10 x 2.5-hour waterproof delays

- 20 x 2.5-hour pencil delays

- 10 x underwater initiators for Cordtex leads

- 20 x 8.5-hour AC delays

- 20 x Bickford fuses.

I believe that quite significant attempts were made to disguise and conceal the presence of this large device. On HMS Campbeltown a main fuel tank is located deep in the hull, behind the forward gun, just forward of the bridge super-structure and about 12 feet down under the main deck, under the Petty Officers’ Wardroom. The top part of this fuel tank was sectioned off to create a compartment. Into this the depth charges were placed in 4 columns, front to back, of six each. The spaces between were then filled with concrete, and a steel lid with (disguised?) access holes placed on top. I assume that the holes was accessed from the deck of the petty officers wardroom. I think any reasonable explosives specialist would fit a cordtex ring main around at least the central depth charges if that were possible.

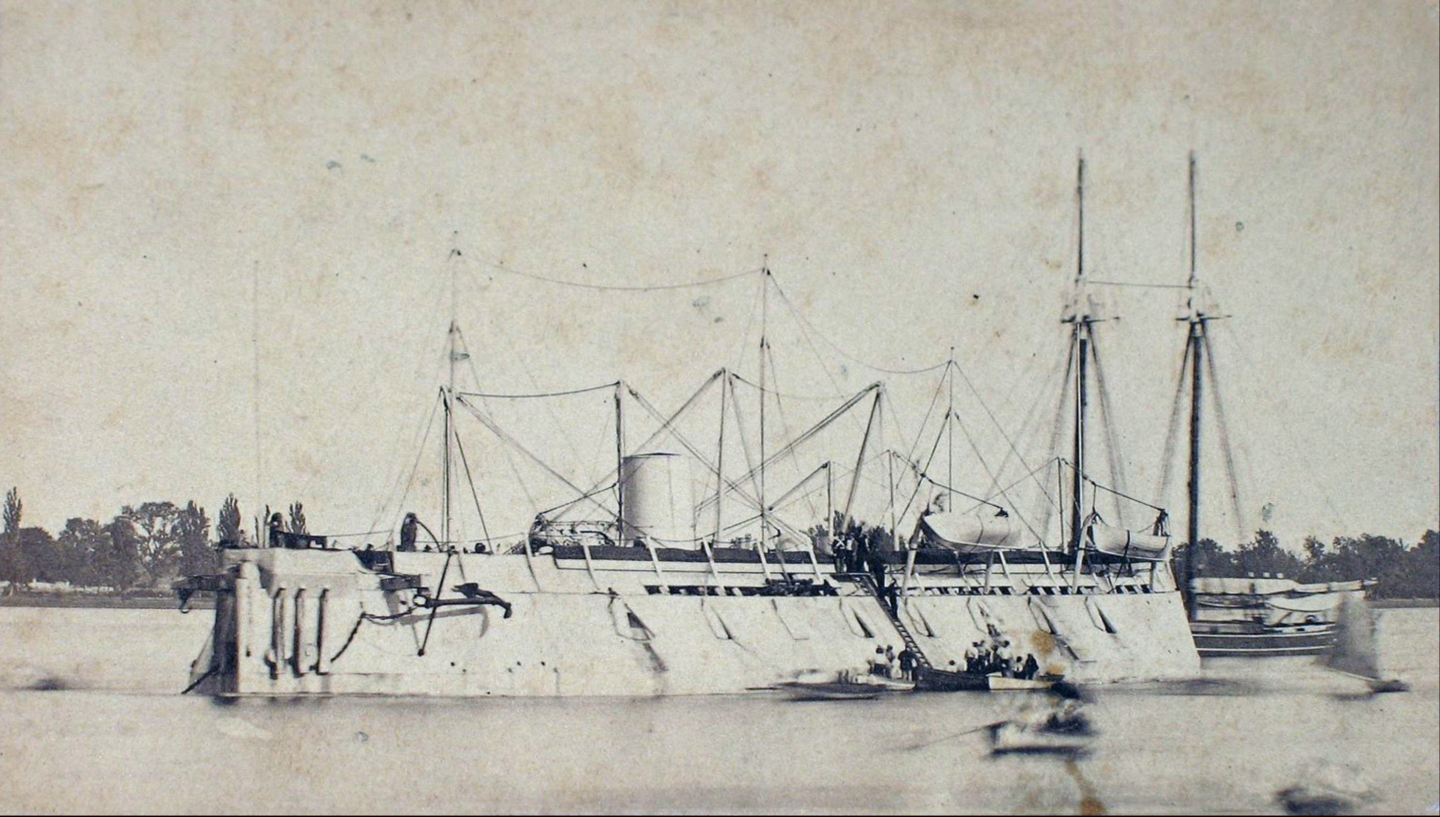

The device was carefully constructed before the operation and I have found the attached photograph of the ship at this time of preparation, in Devonport.

A few things strike me about this photo. This was taken during the preparation for the operation – additional bolt-on armoured shielding is being put in place. But there are several other interesting things in this picture which shows the key deck space above the charge (between the superstructure and the forward gun). Firstly, I think those cylinders at the feet of the seaman are Mk VII depth charges – just at the moment of being loaded aboard – I think I can see six. So that’s interesting. Secondly, so are two of the characters on the picture. Just behind the seaman and the officer are two men dressed in civilian clothes – trilbies and overcoats. They can’t be dockyard workers, as such clothing would be inappropriate. I wonder if they are SOE explosives specialists visiting the preparation to advise on device construction, which one assumes is going on below. Forgive me a little speculation on that! The SOE had a department, at the time called “ISRB” (Inter Services Research Bureau) who conducted research and development of some of the stranger weapons of war. ISRB supported SOE directly but also, and significantly, they supported “Combined Operations” the organisation, under Mountbatten, who coordinated and planned Operation Chariot. ISRB played a key role in developing the AC Time delays, time pencils, sand underwater initiators, so the “shopping list” of components listed earlier looks like they were from ISRB. So I think it’s reasonable for us to assess that the firing system had very significant input from ISRB, who also where masters at disguising and concealing devices. A number of the central depth charges were under the access holes, allowing the charge to be primed. There was a variant of the MkVII depth charge, that had a built in detonator adaptor to allow initiation from a detonator or cordtex , but it’s not clear if this was available to this mission, or indeed if it was developed as a result of this mission’s requirements.

The fuzing of the system is where we have to make a few speculative assumptions, and where there are only a few facts. What follows is a bit of a ramble through the technical aspects.

- The charge had at least two separate initiation systems, and it is very likely indeed that some of these were duplicated to ensure detonation.

- Both the primary and back-up initiation systems employed time delay switches. The challenge here is that many sources contradict each other on the lengths of time delays available, and then after that they are all dependent to a greater or lesser degree on the temperature. I’m conscious that in discussing some of the timings, there are queries over the “2.5” hour time pencil delays and “8.5” hour AC time delays that I have not resolved completely because of conflicting information.

- The primary initiation system was designed to function some time after the ship had been evacuated, probably 2.5 hours after the crew “disembarked”. It probably used at least one (and probably/almost certainly more than one) 2.5 hour pencil delays.

- The planned time between disembarkation and detonation was the reason that the device needed to be concealed.

- I have found one reference (not all that well sourced) that suggests that the primary ignition system (the 2.5 hour time pencils) were hidden, somehow, in the leg of a wardroom table. I’m going to assume that this is the wardroom above the main charge, and that from the time pencil (or much more likely, multiple time pencils) was a detonator(s) and then an explosive link of cordtex that went down the table leg, through the deck below, and into the main charge. But it is possible that the time pencil was connected to Bickford fuse and that the detonator was at the end of this, perhaps inside the false fuel tank attached to cordtex ring main.

- The 2.5 hour time pencils had a white-coloured safety strip. Now 2.5 hours seems like a long time to me, but I think this was because of the other explosive demolition operations planned for the pumping house and other dock facilities – these would explode first, the commandos clear the area, and then the main charge in the Campbeltown would destroy the gates. Exploding the Campbeltown first may have compromised the ability to destroy all the supporting mechanisms. So the concept of operation assumed that the device would be undiscovered for 2.5 hours – (in the middle of the night, during a battle, with raiding parties all around so not unreasonable). The main part of the raid was expected to take no more than 2 hours.

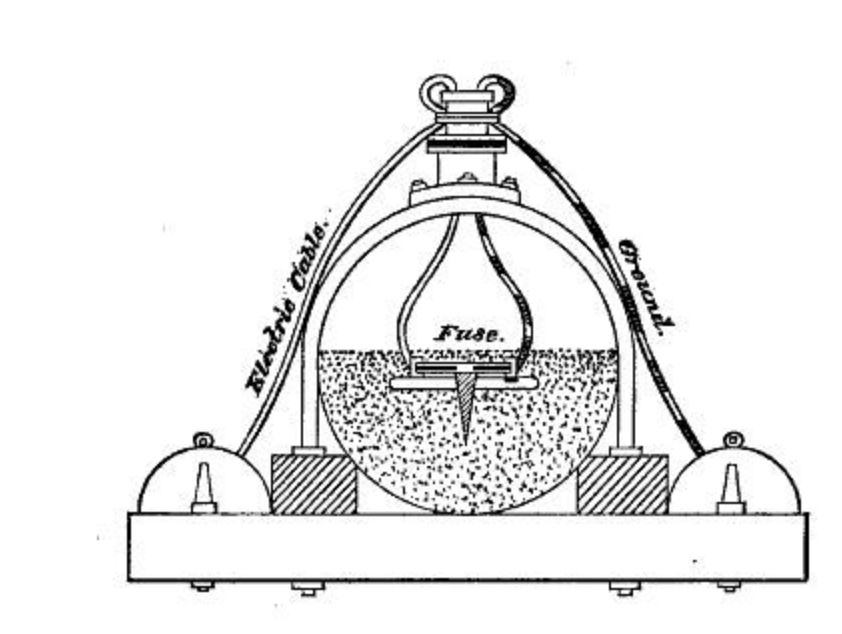

- Now, time pencils are a bit fiddly. They need some inspection during the process of initiating them, involving checking in sight holes, crushing a copper vial, crimping on safety fuze or detonator, inspecting again, and then removing the safety pin. So the hidden compartment would need to allow fairly easy access. We know nothing more of this concealment. I sense the hand of ISRB in this concealment design. It is also possible that they fitted some sort of mechanism to aid the ease of initiation of the time pencils to reduce the fiddly process at the height of battle. here’s a pic of the the pencil:

- I suspect that the plan was for Tibbitts or one of the Royal Engineers to set these immediately after ramming the dock gates. It would have been sensible to assign back up personnel to this task given the expected battle.

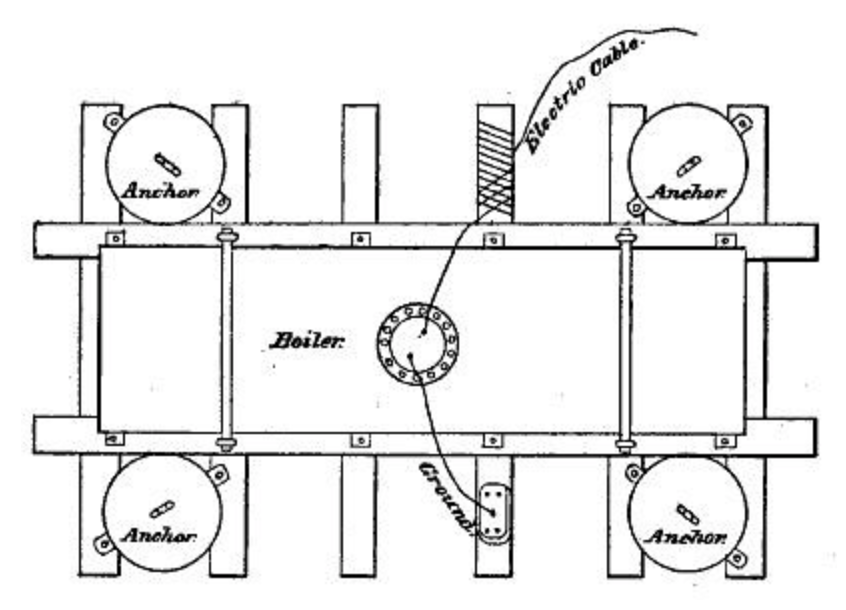

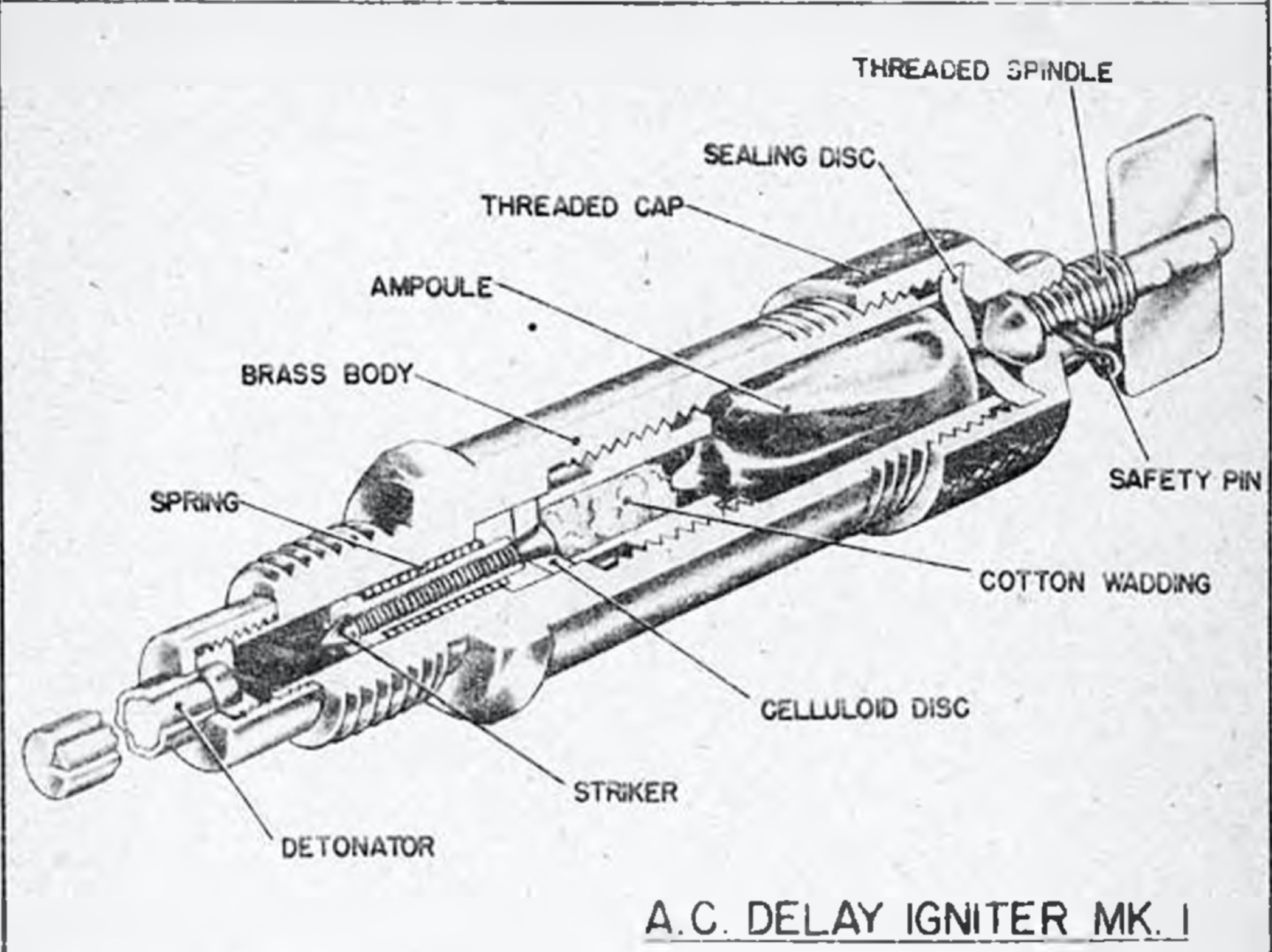

- The “back up” initiation system seems to have involved the use of “AC” delay devices. These involved acetone dissolving a celluloid barrier, and different concentrations of acetone varied the timing. Here’s a picture:

And a photo of one:

9. The delay is varied in these igniters by inserting different coloured ampoules of acetone. They are set by removing the safety pins then screwing the top in to break the ampoules The ones supplied to the Campbeltown were supposedly “8.5 hour” delays, but other convincing sources don’t offer that as an available time delay. So that’s an anomaly I haven’t resolved. These, attached to a detonator, were embedded in the main charge or a ring main (I suspect there may have been a booster of some sort or some cordtex in the mix there to ensure the explosive train). This 8.5 hour timer (if that is what it was) then has the consequence that the charges needed to be set several hours before the final stages of the operation commenced. But there’s some interesting maths here and some challenges.

10. The operation planned for the Campbeltown to ram the dock gates at 0130 hrs. (it did so 4 minutes late, at 0134 hrs.) . The plan must(?) have been for the main delay mechanism. in the wardroom table leg, to be set at that point – with a 2.5 hour delay then the explosion was to have been at 0400. The back up initiation system, to coincide with that, should therefore have been set, theoretically, at 1930hrs the previous evening. Given that that was long before the approach to St Nazaire, and these fuses were known to have reliability issues, I think they would have been set later – hence the delay in initiation until next morning. Added into all of this the AC fuses were known to have quite a range of variation in timing – by as much as 20% due to variables such as the temperature, and also variables in the concentration of the acetone due to poor quality control during manufacture. So some leeway would be given, as well as a fudge factor. As it was , I understand from one source that the AC delays were “set” at 2330 hrs – but I can’t be sure what time zone that’s in – “British” or “local”. Either way, at some point in the night, during passage towards St Nazaire, Lt Tibbits (if it was him) set the AC time delays, I think by reaching somehow through the wardroom floor/deck, setting the devices, (remove the pin, screw the head in) then concealing the access hole with a wooden bung.

11. Then of course battle ensued and things went wrong, as they always do in battle. At some point during the attack, the wardroom was struck by a German shell. Fire ensued, and brave attempts were made to extinguish it. In this picture, taken after the ramming but just before the ship exploded, I think you can see the resultant fire damage to the hull on the outside of the wardroom, just under the forward gun. If you look carefully perhaps you can see a hole where the shell hit.

12. It was probably due to this shell that the primary initiation system was damaged and un-usable. It must also be luck that the device wasn’t initiated at this time, early. So then the attack was relying on the back up AC delays deep in the hidden compartment. The hit on the wardroom also probably made a compete mess of the interior of the wardroom and perhaps added to the reasons why the charge was not found in the ensuing hours. But imagine crewing this ship, sat above (literally) a 3 ton explosive charge, knowing that there’s been a hit and a consequent fire around the initiating systems. Wow. Encouragement to get off as soon as possible I think. Here’s another picture showing how the sea cocks had been opened at the stern to prevent a rapid tow away by German forces.

13. The AC delays finally caused initiation, the main charge having been undetected, at about 10.30 am, perhaps 10 or 11 hours after the 8.5 hour delay (if that’s what they were) had been set. 40 senior German officers and civilians who were on a tour of what they supposed was the captured Campbeltown were killed. Hundreds of others in the dock nearby were also killed or injured. The charge, as you can see from the photo above, was probably 12 – 15ft behind the dock gates, which were blown apart by the explosion. The dock remained unusable until 1947. What remained of the Campbeltown came to rest in the dry dock itself.

I think this photo (taken after the war, I think when the dock was being repaired) shows the immense scale of the Normandie Dry dock, with the little Campbeltown‘s remains occupying the space that would otherwise have held the mighty Tirpitz.

I have taken some liberties here with my sourcing and interpretation of the device design, and I’m very happy to be corrected. some of my assessments contradict some sources. (for instance one source suggests that the device was to be initiated at 4.30 am, others after 0500 am). I put some of this down to the confusion of battle and also confusion over time zones. I think I’d make the following points in summary:

- This attack has so much in common with a number of earlier ship-borne IEDs that occurred on the Channel or Atlantic coasts in the previous 400 years.

- It was fortunate it succeeded, particularly in terms of the enemy fire hitting the place where the primary initiation system was hidden.

- Disguise of the device was clearly a major factor in its construction. The disguise and concealment worked. If one regards this “ship IED” as essentially a large vehicle-borne IED, the key features of a VBIED are all here – mobility, disguise, speed, size of container. As others in history worked out for themselves, (and as you can read on other pages of this blog), as vehicle-borne IEDs go, there are none bigger than ships.

- Exploring the “tactical design” of any IED attack is always fascinating, and the same is true here in spades. Too little time is spent understanding this process (both by perpetrators and by investigators). That complex interrelationship of the mission, and the way that technical resources can be moulded to fit the mission, or the mission tweaked to take account of the technicalities of device design and construction is fascinating. If you were in Tibbits’s shoes, how many back-ups would you have? How would you protect them, from enemy fire and from discovery? What alternatives can you envisage? What other resources did he have available? Complex attacks sometimes require complex devices. Simplicity usually works. For simple, routine sabotage type operations the availability of explosive components leads to the design of the mission. But for complex operations such as this, the components have to be adapted to suit the required characteristics, and that can pose challenges. For those developing components for use by saboteurs, such as ISRB, they have to cover all angles they have to allow as much flexibility as possible and you can see that in the range of timers and initiation types available. There are some interesting parallels, as ever, with modern terrorism.

- The reliance on somewhat unreliable time delay devices is perhaps surprising in modern terms. The whole concept of operation screams for a mechanical rather than chemical timer, or in modern terms an electronic timer.

- We’ll probably never know the actual design, or if there were additional fallback initiation systems.

- IEDs are not always the sole provenance of the enemy. Often viewed with disdain, sometimes depending on your perspective, their use can be heroic. What a strange phenomena they are. Of course you may not regard this as an IED at all, but I do.

- Checking out a large vehicle or ship for hidden explosives is damned difficult if the device is well hidden.

- Bloody hell, it was a close run thing.

I think most of all about the challenge faced by Lt Tibbits. As the Campbeltown approached St Nazaire docks, its guns blazing , under heavy fire from everything the Germans could muster, he replaced two helmsmen, both killed by incoming enemy fire, and he was at the wheel, the skipper by his side, as it rammed the dock gates at full speed trailing the royal ensign that had replaced the ruse de guerre of a German flag minutes before. He knew his primary initiation was gone – so he may have felt significant pressure to somehow ensure detonation. Dare he rely on the back up charges? Given the decks were strewn with injured, that would have restricted his options. Would the device be discovered? What choices were open to him? In any event he was cut down by machine gun fire a few seconds after disembarking and he died there on the dockside and that, I’m afraid, was that for Lt Tibbits.

In future, I may do a similar piece on the WW1 Zeebrugge raid which has a lot of similarities, including another big IED. If I can get enough facts together. One wonders too, that if earlier in the war Operation Lucid had succeeded, would the Germans have paid more attention to the likelihood of explosive charges. Or if they had access to the history of explosive ships along this European coast would they have dug a little deeper into the hull of HMS Campbeltown.