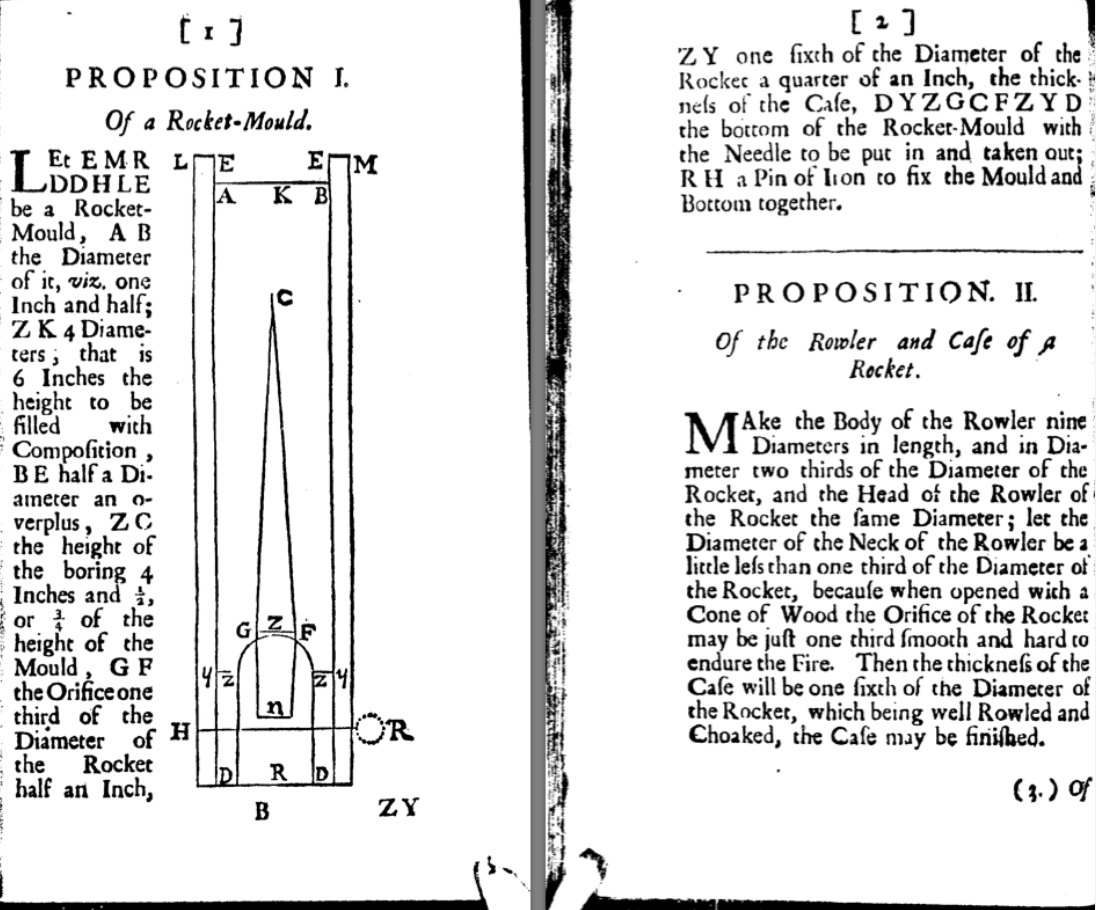

As promised, a quick “connections’ commentary on some pretty remarkable IEDs on ships and boats in history.

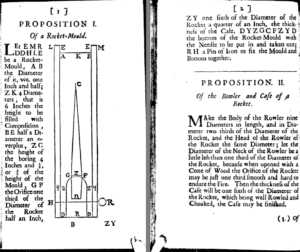

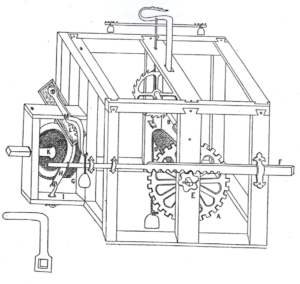

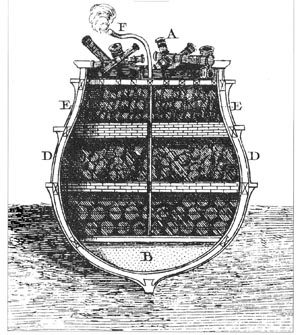

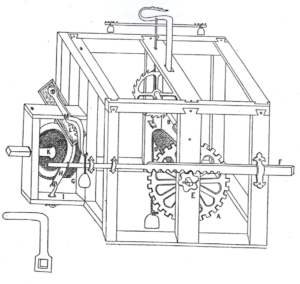

“Fireships” in terms of boats and ships loaded with incendiary material go back in history – I have found reference to them as far back as 413 BC. With the invention of gunpowder, fireships occasionally contained gunpowder. Sometimes in massive quantities. In an earlier blog here, I wrote about the “hellburners”, two explosively laden fireships used by the Dutch defenders of Antwerp in 1584 against the invading Spanish – one of these the “Hoop” (Hope) detonated against a temporary Spanish bridge, killing 800 – 1000 soldiers. If this is true, it is still probably the most lethal single IED in history. I have now found a diagram purporting to the the clockwork timing mechanisms of the device manufacturer by Bory. The Hellburner itself was designed by the Italian Giambelli, who possibly at the time (and certainly later) was an agent of the British.

References I have found recently suggest that Giambelli mounted a series of earlier attacks , floating explosive objects down the tidal river, with limited success. These IEDs were generally floating objects and rafts which carried barrels of gunpowder on a burning fuse.

After these earlier attacks failed Giambelli “thought big” and amidst a fleet of regular fire vessels sailed two explosive vessels (the “Hoop” and the “Fortune”) down the tide towards the target bridge. My earlier post has more details. The “Fortune” had a burning fuse (which I have also fund an description of, but it is too complex to post details here).

The Hellburner incident and the use of explosive ships (described by the Italians as “Maschina Infernale”, and by the British as “Machine Vessels” became well known among the navies of Europe for several hundred years.

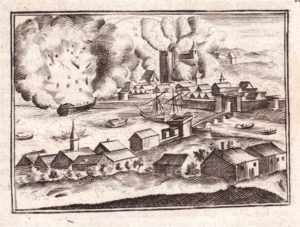

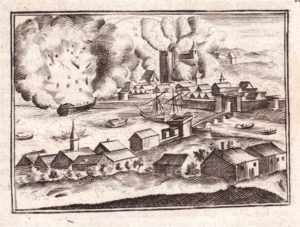

Just over a hundred years later in 1693 the British Navy led by Admiral Benbow used a ship, imaginatively named the Vesuvius, laden with 300 tons of explosives, (other sources say 20,000 pounds of gunpowder) during an attack on the French port of St Malo. The vessel was sailed in by a Captain Philips. The ship did not quite reach its target, became stuck on a rock and exploded “blowing the roofs of half the town”. But causing little loss of life. The capstan of the “machine vessel” was thrown several hundred yards and landed on an Inn destroying it.

Machine ship “Vesuvius”, 1693

The following year in a raid on Dieppe, again led by Benbow a machine vessel was sent in to the port to destroy it. The ship, skippered by a Capt Dunbar was placed again the quay – and the crew and Capt Dunbar left it quickly. Unfortunately the fuze went out – but Dunbar re-boarded the vessel, re–lit the fuze, and evacuated a second time.

The Dieppe Raid, 1694

Similar machine vessel attacks were mounted on Dunkirk in the same year.

(Note: There were a number of vessels developed in parallel at the time , known as “bomb vessels” but these should not be confused with machine vessels. Bomb vessels were essentially ships built to mount and fire mortars. To confuse matters the Vesuvius was a bomb vessel converted to a machine vessel)

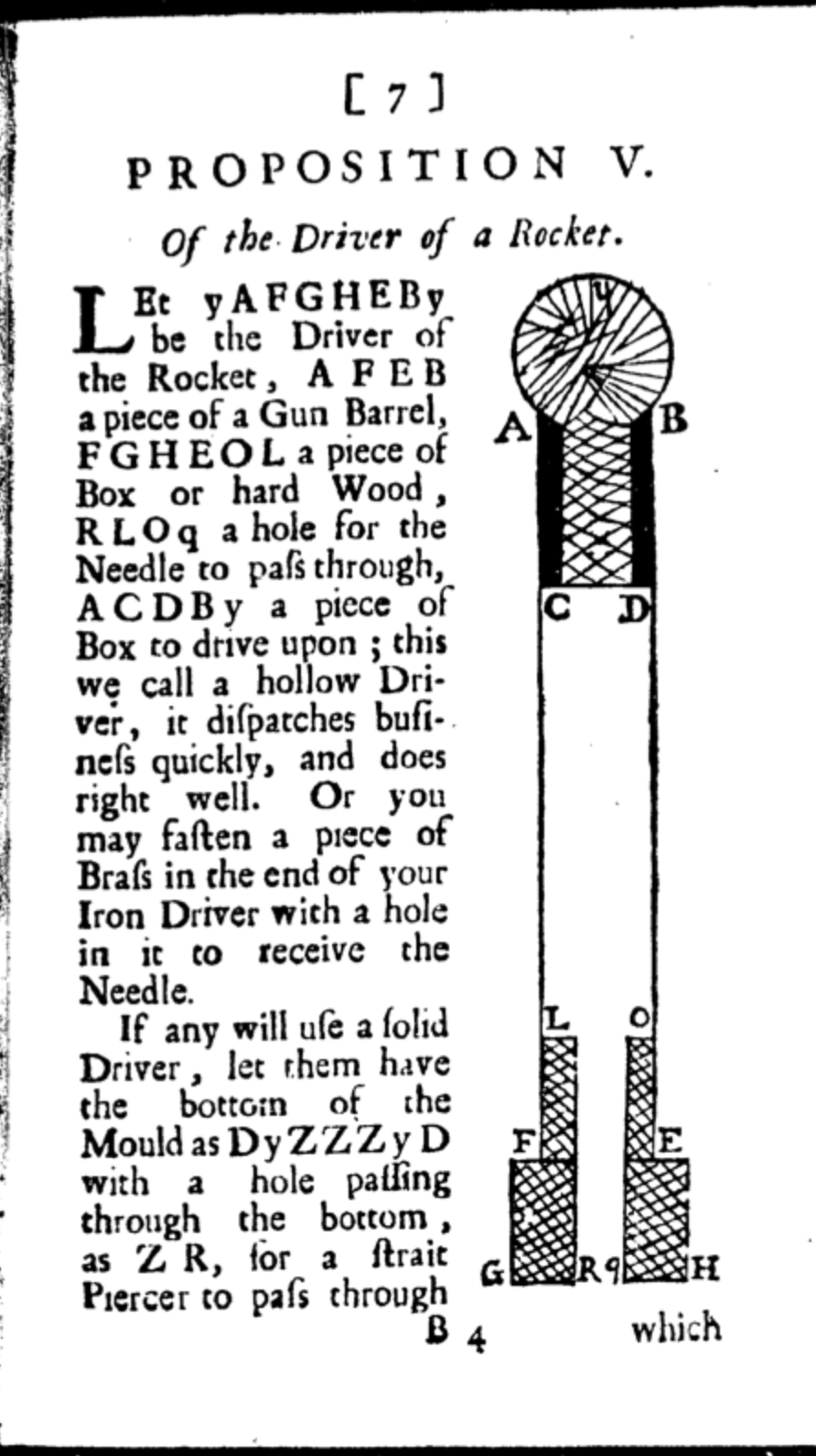

A little over 100 years later in 1809 Captain (later Admiral ) Cochrane used an explosively laden ship in the Battle of the Basque Roads on the Biscay Atlantic coast of France. Cochrane used two explosive ships and twenty-one fire ships to attack the French fleet moored off Ile d’Aix. Here’s Captain Cochrane’s description (who personally set the fuses on one explosion vessel himself)

“To our consternation, the fuses, which had been constructed to burn fifteen minutes, lasted little more than half that time, when the vessel blew up, filling the air with shells, grenades, and rockets; whilst the downward and lateral force of the explosion raised a solitary mountain of water, from the breaking of which in all directions our little boat narrowly escaped being swamped. The explosion-vessel did her work well, the effect constituting one of the grandest artificial spectacles imaginable. For a moment, the sky was red with the lurid glare arising from the simultaneous ignition of fifteen hundred barrels of powder. On this gigantic flash subsiding, the air seemed alive with shells, grenades, rockets, and masses of timber, the wreck of the shattered vessel. The sea was convulsed as by an earthquake, rising, as has been said, in a huge wave, on whose crest our boat was lifted like a cork, and as suddenly dropped into a vast trough, out of which as it closed upon us with the rush of a whirlpool, none expected to emerge. In a few minutes nothing but a heavy rolling sea had to be encountered, all having again become silence and darkness.”

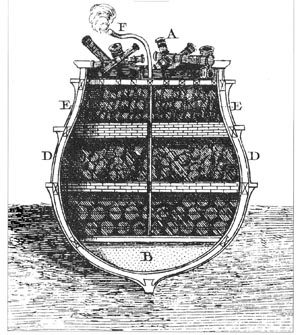

Cochrane went on , in 1812, to design even bigger machine vessels, but never got the political support needed to build or employ them. His 1812 designs used a hulk, rather than a rigged vessel.

“The decks would be removed, and an inner shell would be constructed of heavy timbers and braced strongly to the hull. In the bottom of the shell would be laid a layer of clay, into which obsolete ordnance and metal scrap were embedded. The “charge,” in the form of a thick layer of powder, would next be placed, and above that would be laid rows and rows of shells and animal carcasses. The explosion ship would then be towed into place at an appropriate distance from anchored enemy ships, heeled to a correct angle by means of an adjustment in the ballast loaded in the spaces running along each side of the hulk between the inner and outer hulls, and anchored securely. When detonated, the immense mortar would blast its lethal load in a lofty arc, causing it to spread out over a wide area and to fall on the enemy in a deadly torrent. Experiments conducted with models in the Mediterranean, during his layoff, convinced Cochrane that three explosion ships, properly handled, could saturate a half-mile-square area with 6,000 missiles–enough destructive force to cripple any French squadron even if it lay within an enclosed anchorage.”

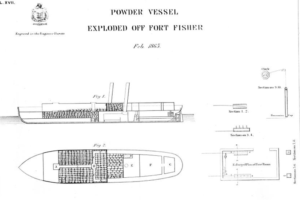

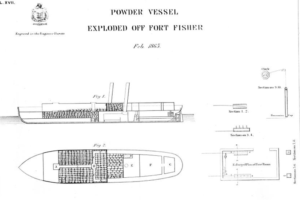

In 1864, during the American Civil war an explosively laden ship, the USS Louisiana was used to attack a Confederate fort, Fort Fisher, guarding Wilmington, North Carolina. The ship was meant to be run aground adjacent to the fort walls and then detonated. The ship was carrying “215 tons of explosives”. The attack failed as the Louisiana detonated too far away from the fort walls to cause damage.

Here’s a diagam of the ship. Note the huge amount of explosives. I have obtained a detailed description of the numerous initiation systems and fuzes but it is too complex to post here easily. Suffice to say there were 5 independent firing systems.

USS Louisiana, 1864

Just over a fifty years later the Zeebrugge raid of 1918 saw the British Royal Navy again use an explosive vessel, this time the submarine C-3, under Lt Cdr Sandford. Sandford was subsequently awarded the Victoria Cross.

“This officer was in command of submarine C3, and most skillfully placed that vessel in between the piles of the viaduct before lighting his fuse and abandoning her. He eagerly undertook this hazardous enterprise, although well aware (as were all his crew) that if the means of rescue failed and he or any of his crew were in the water at the moment of the explosion, they would be killed outright by the force of such explosion. Yet Lieutenant Sandford disdained to use the gyro steering which would have enabled him and his crew to abandon the submarine at a safe distance, and preferred to make sure, as far as was humanly possible, of the accomplishment of his duty.” After pushing the submarine under the piles of the viaduct and setting the fuse, he and his companions** found that the propeller of their launch was broken, and they had to resort to oars and to row desperately hard against the strong current to get a hundred yards away before the charge exploded. They had a wonderful escape from being killed by the falling debris.

Damage caused by the detonation of the C-3 – Zeebrugge 1918

The final one from this series is Operation Chariot, aka “the Greatest Raid”, the British Navy and commando raid on St Nazaire in 1942. I won’t repeat the story, other than provide this link to the Wikipedia article – not many Wikipedia articles make the hairs of my neck stand up, but this one does. In this raid, HMS Cambeltown was converted into a massive IED and rammed into the docks in St Nazaire to prevent their use by the German Battleship Tirpitz.

HMS Campbeltown rammed onto the dock gates in St Nazaire, before she exploded. 1942.

One big concept – massive IEDs in ships, woven through history.

I have much more to post on historical naval IEDs. Be patient!