I am fortunate to have “inherited” an archive of historical material from “IJ” which I am slowly cataloguing. I can’t help but to dive in on some of the historical documents which although perhaps not connected with IEDs and EOD have a broader historical interest in those interested in explosives. One particular set of documents relate to the latter part of the 1800s when the UK was undergoing a period of regulatory development of controls on the production and storage of explosives. Until then it appears that safety and good practice were unregulated and the industrial expansion of the explosives industry was little constrained, and as a result a number of accidents occurred. This led to investigations by military officers (first Lt Col Boxer RE in 1864, and later by 1874, Major (later Colonel) Majendie RA. I have often mentioned Colonel Majendie in earlier posts as he was really the first “formal” practitioner of both Improvised Explosive Device Disposal and what is now called Weapons Technical intelligence in relation to IEDs.

As I looked at the early reports by Col Boxer and Maj Majendie I was struck by some similarities in a major explosion that occurred in Erith and the recent explosion in Beirut. I propose no particular comment here on the Beirut explosion other to say that I was disappointed at the volume of technically illiterate comments in the news media. But it is interesting to see how two events in 1864 caused the establishment of suitable regulatory control. The two events, which I’ll discuss below, and a number of other explosions in the latter part of the 1800s heightened public and government awareness of the safety issues in the manufacture and storage of explosives, and the appointment of Majendie as the lead government authority on the matter of explosives also provided him, inadvertently but happily, with the powers to investigate IEDs.

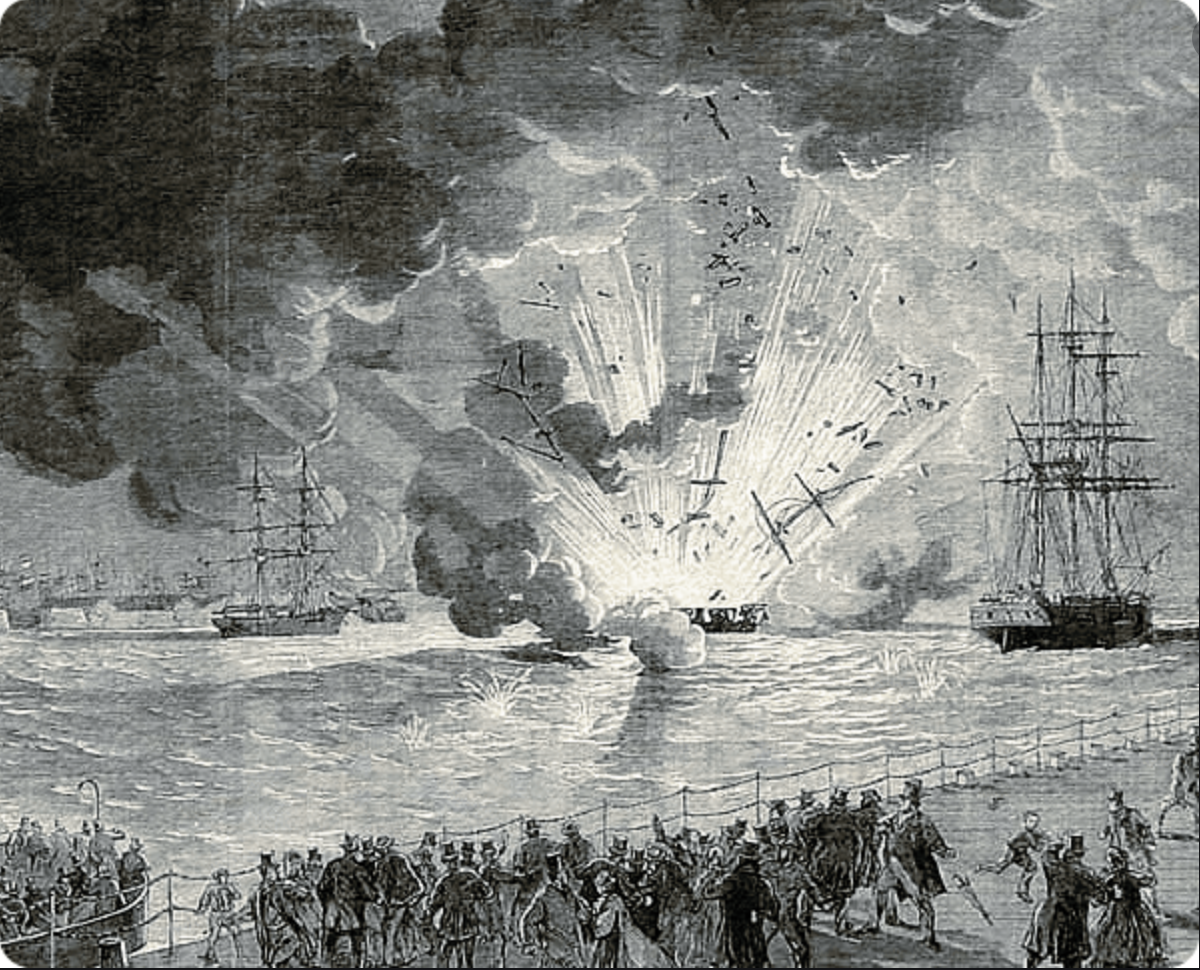

The first incident in 1864 was the explosion of the “Lottie Sleigh” a sailing barque carrying 11 tonnes of gunpowder on the River Mersey on 15 January 1864. A sailor aboard knocked over a lamp causing a fire. All the crew “baled out” and were picked up by a ferry. Shortly afterwards the unmanned vessel exploded. No-one was killed but the damage on both sides of the Mersey was significant. Thousands of windows were broken and doors were blown open in both Birkenhead and Liverpool and most of the gas lamps in the streets of Liverpool were “blown out”. The explosion was heard 40 miles away. Subsequently insurance companies were involved in complex process to assess liability. Here’s a pic of the vessel exploding:

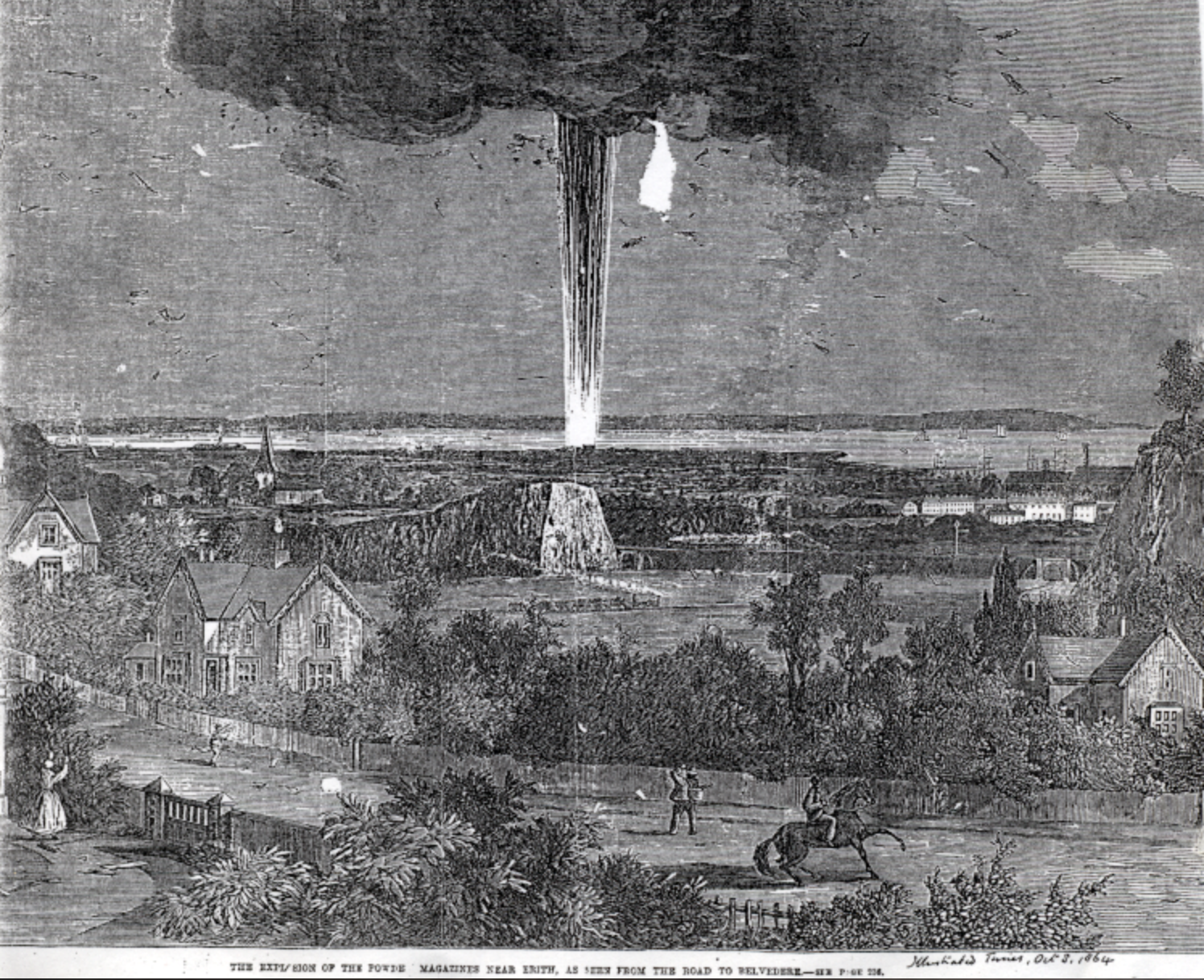

Later that year, on October 1st two storage warehouses containing a total of 50 tonnes of gunpowder exploded at Erith on the Southern Bank of the Thames, not far from Woolwich. No cause of the explosion has ever been established. The explosion was felt 50 miles away. The store was adjacent, like in Beirut, to some docks,

This quote helps us understand the significant devastation:

Everything within its reach was annihilated. Man and matter perished together, shivered into a thousand fragments and whirled into space. People know there used to be a magazine in the Erith marshes, but there is now only a yawning crater there. The very ruins are lost. A visitor to the spot went to look for a cottage which he

remembered ; it had been ” swept entirely away, as with a broom.” Every witness whose evidence could have thrown light on the catastrophe has been hurried out of the world by that tremendous thunder- clap. Those immediately concerned can hardly be returned as killed-they are “missing”-that is to say, their very bodies have disappeared.

Property was damaged 20 miles away but only 10 people died.

These two explosions caught the imagination of the public and communities adjunct to “powder stores” up and down the country. There seems to have been a campaign by many of them to write to the Home Secretary to request oversight of the storage of explosives, and so Lt Col Boxer RE was tasked with inspecting many of these sites up and down the country. In effect this became the first Report of the Chief Inspector of Explosives, a report which became annual under Major Majendie 10 years later and which provide today a treasure trove of historical research. I have copies now from 1864 and then from 1874 till recent reports.

The Erith explosion has a number parallels with the Beirut explosion. Lessons can still be learned 150 years later. Alas, this was not the last explosion in this vicinity. There was an explosion at Woolwich in 1883, and another in 1907. In World War One (1917) there was a massive explosion of 50 tons of TNT in Silvertown docks on the North bank of the Thames nearby. Weirdly there was another explosion at a factory in Erith 4 months ago.

I have somewhere a catalogue of such accidental explosions in history, a remarkable number, which perhaps I’ll pull together in blog post – going back hundreds of years. Bottom line – every explosive store should be sited and managed on the presumption that it will explode. Major Majendie’s report of 1874 is a fantastic “tour de force” of the explosives industry of the time and the needs of detailed explosive regulations – I’d recommend it to anyone with an interest in explosive storage.