I continue to uncover remarkable details of the Boer IED campaign against the British in South Africa. I have detailed some of these in previous posts and railway attacks here in particular. What I hadn’t quite realised was the scale of the campaign, which is huge, and indeed provides a template not only for the Russian partisan campaign against Nazi railways of WW2, but also in a sense the insurgent campaign in Iraq in 2003/2004. Also see my other posts on railway attacks by clicking on the link of subjects in the right hand column – quite a few over history, including Lawrence of Arabia, the German East African campaign of WW1 and others.

The details I’m going to show you highlight that this was very much a strategic campaign targeting the British Military’s ability to move around South Africa. It also goes to demonstrate a comprehensive range of operations by the British military to respond to these IED attacks, by repairing the railway system, maintaining it, and implementing a range of C-IED security measures, not least being the “blockhouse” concept where small detachments of soldiers established patrol bases at frequent intervals along the railway.

I think it’s important to mention that the Boers were particularly effective at targeting the railway in a number of ways:

- By taking out key bridges. The number of bridges destroyed and then either repaired or replaced by the British Army is staggering. The Boers had significant numbers of personnel familiar with using explosives, and no lack of explosives.

- By blowing numerous culverts were the railway line crossed them.

- By damaging rails.

- By attacking trains and rolling stock either moving on the line or in sidings. sometimes by explosives and sometimes by simple sabotage such as removing key components, or by fire.

- By attacking supporting infrastructure such as watering points and water supplies. Coal supplies were set alight in depots.

There were of course plenty of Boers from the mining community with the experience to set and lay simple charges, and the IED technology evolved over time. My guess is that with no great shortage of explosives, a knowledge of what explosive placement and quality to use evolved rapidly over time – certainly the images below suggest sufficient expertise (or sufficient quantities of explosive) to blow large structures.

A variety of devices initiation methods were used:

- Simple burning-fuze time detonation for bridges, and track where no enemy was present.

- Command wire attack in an ambush situation on a train coming down the line, so the Boer’s were in sight of, but a tactical bound away from the site of the explosion.

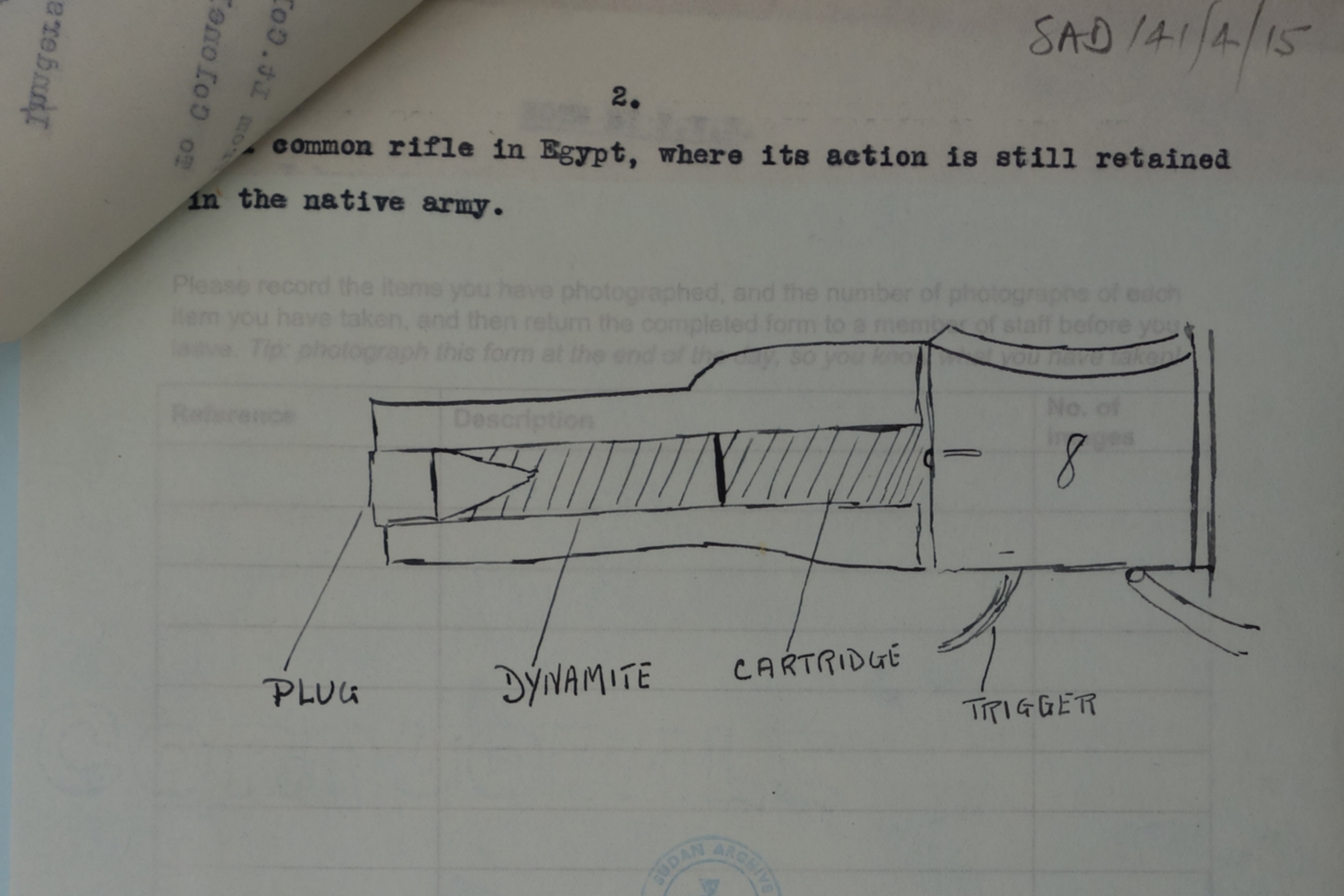

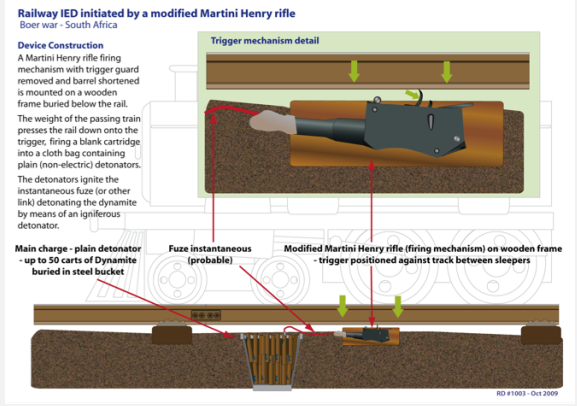

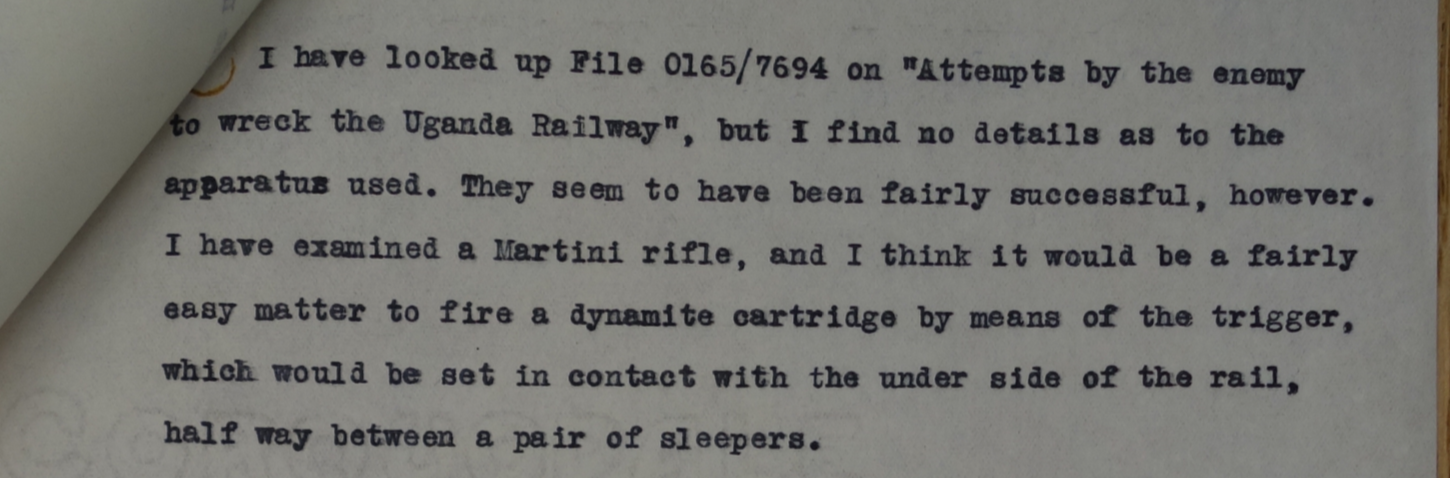

- Victim operated devices placed under rails which were initiated by the train (as discussed here)

I’ve obtained a copy of the report written by the British Army Royal Engineer responsible for running and repairing the railway, where he details a lot of the repair work undertaken – from these I can derive details of the successful IED attacks over quite a period. To be clear, this account doesn’t focus on the IED attacks themselves in particular but the running of the railway as a system, and with the repair process as a part of that but we can draw useful analysis of the IED campaign against the railways from it. So here’s some summaries and exemplar detail. I should mention that the name of this Engineer officer is Édouard Percy Cranvill Girouard. (!) Or rather Lieutenant Colonel EPV Girouard KCMG, DSO, RE, to give him his full title.

- Largely because of the distances involved, the British Army, relied extensively on the railway system for strategic movement and routine logistics. There were 4600 miles of track in the system in a series of interconnected networks.

- The British Military took over the operation of the railways completely in 1899, retaining local staff were possible. There were, of course, challenges were railway works were Boer sympathisers. This was a managerial challenge. A huge “lesson-learned” for the Royal Engineers was the need to develop competency in complex railway systems management.

- Repairs to the railways were often carried out under fire, or at least in the presence of the enemy

- Water is a crucial component of running a steam railway and the Boers realised this and disrupted water supplies too. The British on occasions resorted to running “water trains” to supply water for other trains. At one point the entire water supply for the railways around Bloemfontein was cut by the Boers from April 1900.

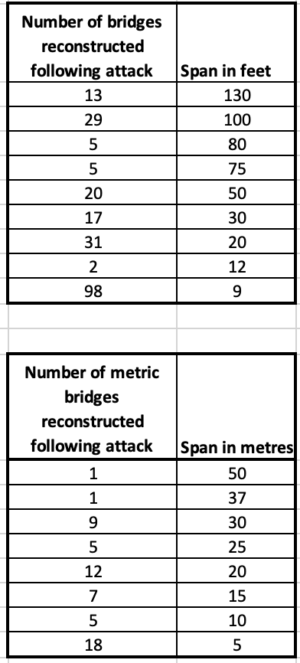

- The number of bridges damaged by explosions is significant. here’s a summary of bridges reconstructed following an attack – divided into two lists depending on whether they were built originally in imperial dimensions or metric:

So that’s a total of 278 railway bridges requiring reconstruction following attack by the Boers with explosives. After these were repaired, military posts were set up to guard every span over 30ft – leaving only smaller bridges, culverts and regular track as the target for Boer IEDs. As you can see, that’s quite a manpower bill in itself in terms of a counter-IED strategy. Later, blockhouses were set up providing a blockhouse protected against rifle fire and surrounded by barbed wire every 2000 yards along the railway lines, each manned by a small number of troops (about ten each) – quite an investment in resources, but crucial to keep logistics functioning.

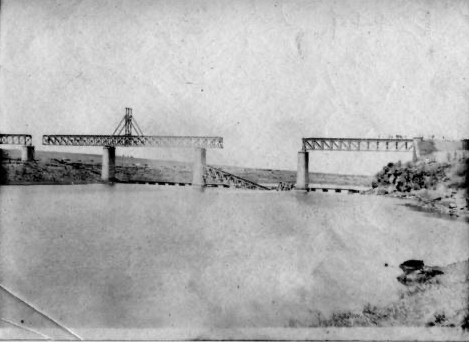

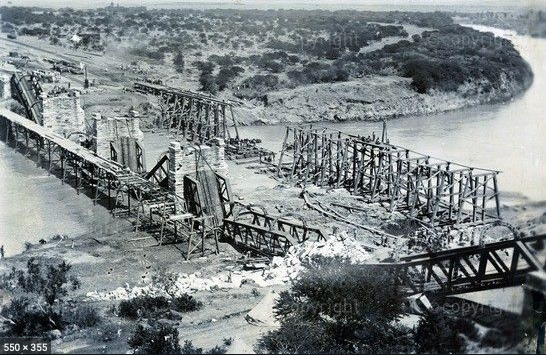

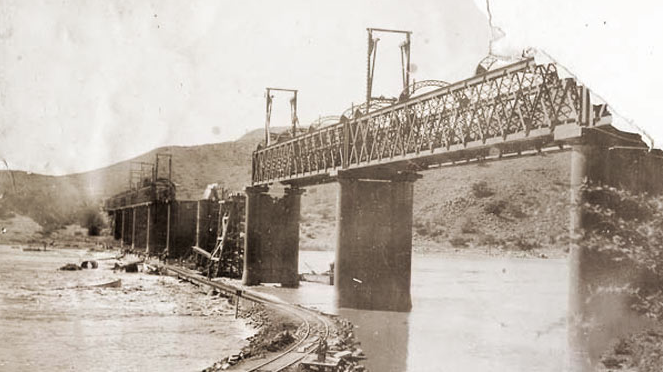

Here’s just a few of the bridges damaged by Boer IEDs, and subsequently repaired:

The Modder River Bridge:

The Vaal River Bridge:

The Colenso Bridge over the Thukela river with two parallel Royal Engineer replacement bridges being built (often under enemy fire)

The Orange River bridge, with replacement bridge alongside

The Norvalspont Bridge: This bridge was repaired in 14 days, or at least a secondary Laine installed (see the rails at the base)..

The Bridge at Fourteen Streams

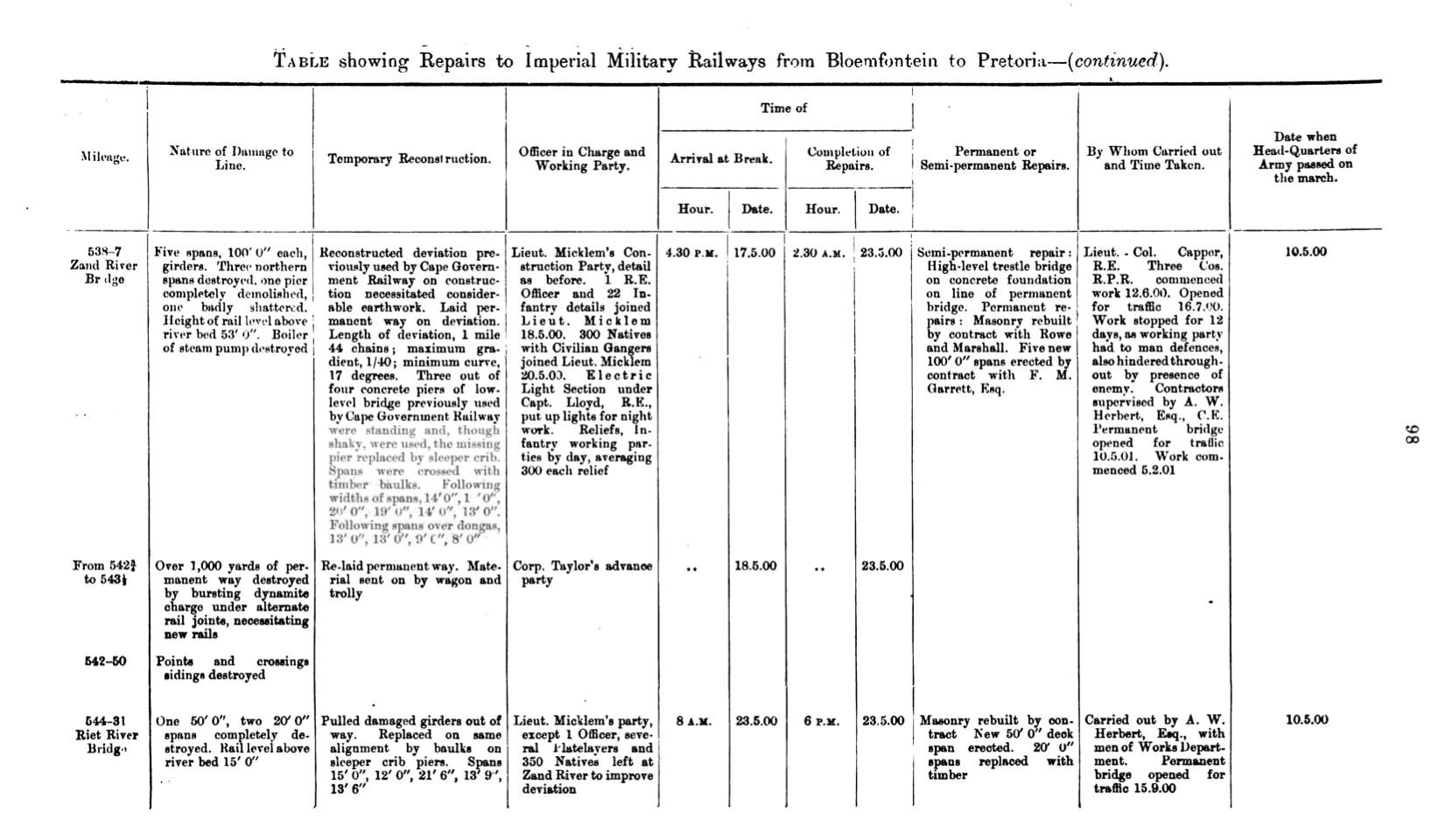

I could post many more pictures of IED damaged bridges, but I hope I’ve got my point over that this was a strategic IED campaign, and required a strategic repose from he British Army. The files I have obtained detail the amazingly short periods of time it took the Sappers to temporarily rebuild many of these significant bridges. Here’s an excerpt of just one page of dozens more, note the speed of the engineer operation:

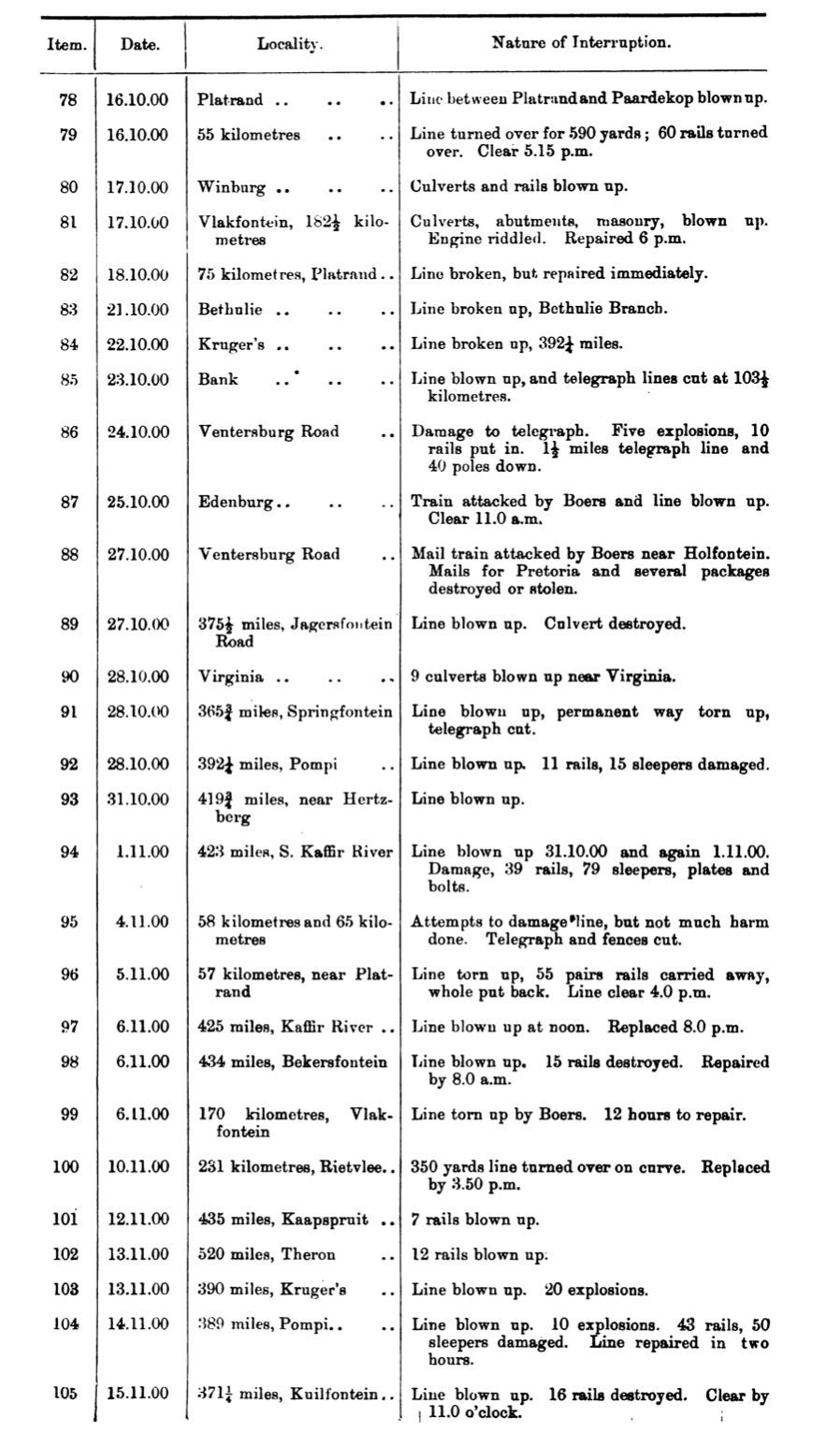

As well as these major bridges, many smaller bridges were also blown along with probably hundreds of culverts. Lines and points were damaged either by pulling them up or damaging them too with explosives. To give an idea of intensity of IED attacks, this is an excerpt listing just one month of attacks on just one part of the network:

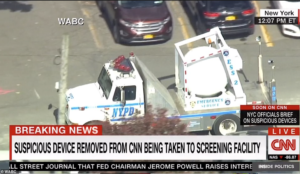

With the adoption of the pressure sensitive IEDs used by the Boers, train engines were armoured to protect the crew and then trucks were pushed ahead of the engine on every “first train of the day” as sacrificial elements to initiate any IEDs ahead of the train.

One particular counter-measure against IEDs that I have discovered fascinates me and returns to the theme of Remotely Operated Vehicles. An “inventor” in England suggested deploying a carriage powered by a heavy electric motor some distance ahead of the engine, to which it was connected by long electric leads. So a wire controlled ROV on rails, in effect. This was trialed in theatre (like sometimes such ideas still are!) but found to be impractical, for the following reasons:

- It was sacrificial and was expensive in itself to be replaced.

- It was difficult to control, keeping the wires sufficiently taut so the train didn’t run over them or have the leads pulled from the controller.

- The wires caught in any trackside object (including trees, blockhouses, telegraph poles etc.

- It couldn’t cope with curves without causing more problems.

- The Boers had already started using electrically initiated command wire IEDs anyway, so could ignore the ROV.

Nonetheless this demonstrates, that even in 1901 that innovative ideas were being sought to deal with IED threats. And .. it’s another early ROV.

With regards to other innovations, this next one is a bit peculiar too. Over time the “blockhouses” placed 200 yards apart were added to so there was even less distance between them. The gaps between were under observation (in some cases at night with the use of searchlights) to prevent insurgents placing IEDs on the rails and patrolled frequently. Do this was a strategic effort to observe all of the communication routes used by there British. Another innovative concept implemented, I kid you not, was the use of specialised bicycles. These “war cycles” consisted, at first, of two bicycles, fastened on a common frame with wheels adapted so that the cycles ran on opposite rails. two sliders would pedal between blockhouses providing route coverage. The adapted wheels enabled the cyclists to use both hands to fire weapons , and progress was relatively stealthy. Later, a larger “8 man” war-cycle was built proving more firepower. a lot of these machines were made in Cape Town and used by the Royal Australian Cycle Corps.

Other innovative responses to attacks included this fabulous add-on armour to a train (admittedly not necessary against IEDs). British soldiers, almost inevitably, came up with the nickname:

The conflict also prompted innovative use of other battlefield technologies such as armoured vehicles, and use (by both sides) of wireless radio communications – perhaps a first in a conflict.

To summarise, I think we can see in this conflict:

- A strategic and extensive IED campaign by the Boers as a part of an insurgency campaign. The patterns of similar strategies with later campaigns up to the modern day are clear, and in particular the Russian inspired partisan campaign against the Nazi rail system in WW2.

- A coherent response of sorts from the British Army, in terms of resourcing appropriate management control of the crucial national rail network

- A component of that response included resourcing repair teams and military engineering capabilities of sufficient size and flexibility to respond to the intensity of IED attacks

- A manpower intensive (but ultimately successful) security operation to protect the exposed logistic capability

- A search for innovative counter IED methodologies and ideas, some of them implemented successfully but time wasted on others. Sounds familiar.