In recent years various terrorist groups and others have used land, sea or air ROVs to deliver explosive payloads to targets. As usual, people view these things as new and innovative threats. But as readers of this blog site will know, that usually isn’t the case and I have more details here of some interesting early use of such devices from WW2, although they go much further back. Some of these may be classed as “improvised” but others are clearly formally developed systems – but let’s not get hung up on definitions, because the concept is what is interesting There are several aspects to this – one is the technology that is used, and another is the tactical employment. Many of the implementations of this concept were unsuccessful but the reasons for this are also interesting and indeed are being repeated in modern terrorist use of ROV technology. I won’t go into that aspect in too much detail for obvious reasons. So here goes with a few interesting German “land based” example ROVs from WW2.

I’ve written before about the WW2 German “Goliath” remote controlled mine, a small tracked vehicle not too different in scale from modern EOD ROVs. Following the fall of France in WW2, the Germans captured a prototype French ROVs used for explosive charge delivery which seemed to inspire the development of the Goliath. This vehicle had been “hidden” in the River Seine, but the Germans got to hear of it and salvaged it for technical exploitation and reverse engineering. (Readers may recall a similar reverse engineering operation from a “purchased” French speed boat just before WW1, that I discussed in an earlier post).

Captured German Goliath ROVs after D-Day

While there has been some attention on the Goliath tracked vehicle, used to deliver demolition charges to targets, perhaps just as significant for us looking at history was the German Borgward B remote tracked vehicle. A contract was let by the Wehrmacht to the Carl Borgward engineering company in Bremen for 50 tracked vehicles in 1939. It’s not quite clear if the Borgward B was developed originally to deliver demolition charges or for other purposes such as towing mine clearance tools or as an ammunition carriers. One suggestion is that during the German invasion of France, German engineers found an operational need and had been converting, in an improvised way, standard German tanks to operate remotely for certain tasks. The theory goes that as a result of after-action reports from this campaign the Borgward B was converted to fulfil this role. But it’s war and it’s a little confusing as to which came first, the chicken or the egg. In any event, Blaupunkt, the radio manufacturer developed a radio controlled system for the vehicle. These vehicles and their sub-systems were gradually improved in following years resulting in several “versions” as both their use and requirements changed. A variety of vehicles were used as “control” vehicles as the war progressed. The radio control unit was very “modern” in appearance, using a joystick control and shared many of the features of the Linsen boats control systems. The key features of the Borgward B was firstly that it could deliver a large charge, (typically 45o – 550kg), and secondly it could drop off the charge and retreat, thus in principle being a re-usable vehicle, unlike the smaller and disposable Goliath.

Here’s a pic of the Borgward B. The driver would drive the vehicle “normally” until it was a “tactical bound” away from the target, then he would get out and the vehicle would then be controlled by radio remotely. It looks like a fun drive, (unless you are told to drive it to the Eastern Front).

The Borgward B wasn’t a huge success. it was unreliable and quite vulnerable to enemy fire. Some reports suggest that some versions were equipped with smoke units to lay smoke screens or just to hide its own approach, but I’m not sure how it would then be controlled if surrounded by its own smoke screen. Perhaps this version was simply used to lay smoke screen and move laterally across the battlefield. I have found a report that a single Borgward B was fitted with a TV camera as an observation vehicle during the fall of Berlin, perhaps a prototype but in the main the later use of these vehicles, in theory was to deliver and drop demolition charges. The explosive charge, when dropped, had a timer initiation system that after a short period caused the charge to detonate. The charge was released with the help of gravity after explosive retaining bolts were fired by the operator. I’m cautious about this and think it could have been a lever actuator. It appears that there was an adjustable safety mechanism that armed the charge only after a certain distance (not time) had been covered, so for instance an operator would set the safety distance to 100m as he exited the vehicle, and the charge would only become “armed” after the vehicle had covered that distance. That’s logical, but I’m not sure how it was achieved. These vehicles were less suited, of course, to defensive operations than offensive, where their utilisation against defended structures was optimised. I’m led to believe that over a thousand Borgward Bs were produced (compared to many thousand Goliath vehicles).

Here’s a great pic of the explosive charge after being “dropped off” by the vehicle. You can see it slides off the front plate where it is held in a “shoe”.

I think it’s worth thinking about the relative strengths and weaknesses of the Borgward B and the Goliath. The Borgward B could be moved into its tactical launch position by one man, but the Goliath needed a small team of men. Perhaps that’s why the Goliath was used in defensive positions like the beaches of Normandy, where it was prepositioned in shrapnel proof hides, (but it wasn’t particularly effective). The Borgward B was larger and therefore more vulnerable, but delivered a much bigger charge than the Goliath more suitable to taking on defensive positions. The Borgward B was more expensive but in theory was reusable. In the main the Borgward B was radio controlled and this offered some flexibility but also posed some reliability problems with the technology of the day. The cable system principally used by the Goliath was more reliable but vulnerable to shrapnel damage.

There was an attempt at a “middle ground” the NSU “Springer” ROV developed in 1943/1944. This was smaller than the Borgward B, bigger than the Goliath, but was driven into launch position by a driver. About 50 were made, I think. Here’s a picture showing its scale and size. They seem to have limited operational use. I don’t have a handle on their control system.

I think it’s fascinating that the Germans also used vehicles captured from the British and French and convert to ROVs. It seems that the German engineers saw potential in particular from the British Bren Gun carrier and the Belgian “utility tractor” (a British built tracked vehicle made by Vickers, who also made a proportion of the British Bren carriers).

Here’s a pic of both in “normal use”

A Belgian Vickers Utility tractor

Bren Carrier

A number of both these vehicles were converted to be cable-controlled demolition vehicles, each with a 1.2 km cable. That’s quite a distance, and one imagines that control of vehicle at such range was tricky, based on distant observation. A total of 60 were sent to the Crimea in 1941. The German Crimean campaign of 1941 is interesting because I think it was used as a testing ground for range of innovative German technologies. I’m currently exploring the use of an advanced prototype German fuel air explosive weapon in this campaign, to clear bunkers and defence structures, and it appears that these converted Belgian and British ROVs were used against the same targets to deliver relatively large explosive charges. I have also seen reports of Borgward B vehicles used in the Crimea at this time. It appears that the majority of the 60 vehicles were deployed with mixed results – some destroyed by mines before they reached the targets, some destroyed by enemy fire, some failed and some functioned as intended destroying Russian defensive positions. I can find no specifics over the amount of explosives carried by either vehicle, nor any specifics on the control mechanisms fitted. It appears that the ROVs were “controlled” from a “mother” command tank. The Germans complained that there were no spare parts for the captured ROVs and recommended development of indigenous vehicles accordingly. Other feedback included the suggestion that they would be better employed in flatter, desert conditions, such as North Africa, rather than the complex urban defence environments of Sebastopol, and indeed at least one Bren carrier, captured at El Alamein was so converted. While this effort to convert enemy tracked vehicles to wire guided demolition use wasn’t really repeated , it’s clear it had some success and more importantly allowed the Germans to develop tactics and concepts of operation. . I think too, given the large amounts of “enemy” vehicles abandoned in Europe at Dunkirk and elsewhere, it made economic sense to utilise them, and the Germans had no qualms about recovering, and using, where possible, quite a range of enemy equipment.

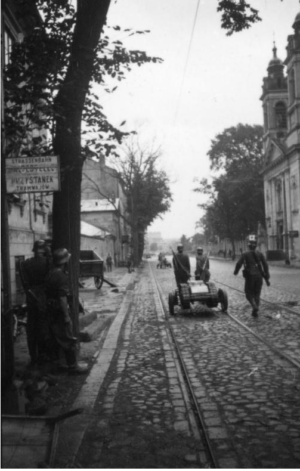

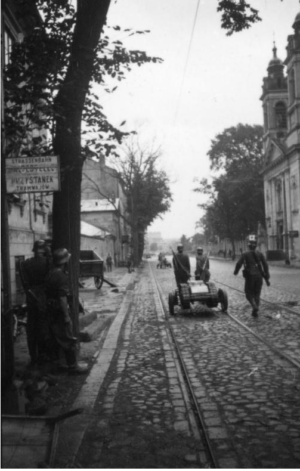

This picture is, it is claimed, a captured Bren carrier (complete with German Cross) fitted with explosives being deployed on the Eastern front. The vehicle in the distance is Borgward B, I think, so it seems very likely.

I think it’s fair to say that the Goliath and the Borgward B ROVs were less effective than the Germans had hoped in normal operations on the Eastern and Western fronts. But it’s worth looking more closely at their deployment in the tight urban environments of cities. There are notable reports of Goliaths being deployed into the Warsaw Ghetto in responding to the Warsaw uprising in 1943. If ever there was a historic precedent to the urban destruction seen in modern day Syria, the destruction of the ghetto by the German in 1943 is it. Goliath were used to target buildings, and of course with only small arms the defenders had little defence against these ROVs, unlike formal military units. I also see parallels with modern anti-tank missiles being used against defensive positions in Syria, of which we are seeing many. Yes these aren’t as fast as those missiles but the targets and tactics are quite similar.

Here’s the remains of a burnt out Borgward B vehicle, I think destroyed by fire after it had dropped off its charge in Kilińskiego Street in Warsaw in August 1944. The explosion reportedly killed 200 residents. The story of this attack is dramatic and a desperately sad tragedy. Essentially the vehicle had been captured by Polish troops as the Germans attempted to deploy it towards a road block and was being paraded around Warsaw by cheering locals. Someone pulled a lever which caused the deployable explosive charge to slide off, and as we know there was a timer started by this activation which the crowds did not understand. The charge detonated shortly after. There is more detail here if you are interested. It is possible of course that this was a “Trojan horse” attack, and a number of sources claim this but I suspect that it was just accidental.

Here’s some pics of the Goliath systems being deployed in Warsaw.

This is the effect of a Goliath on a building in Warsaw

I think the German forces of WW2 had, in their ROVs, some interesting tools for offensive operations, and for the built up environments of Warsaw and heavily prepared defensive environments off Sebastopol they were of some use. But for German defensive operations, they were less suited. Fundamental unreliability was a major issue, it seems, with all the systems they used, and that’s both in terms of motive power and in terms of the control systems. Modern technology perhaps allows for more reliance on the systems used by terrorists and others. In a battle there is perhaps more of an issue of unit cost – whereas modern ROVs are cheaper, and not being deployed, in general, in battle conditions are doubly attractive. Modern ROVs have more precise controls including reliable and usable video components that makes control easier and more attractive. More accurate control also leads to the potential to reduce charge size and so allow the vehicle to be smaller. I think this aspect of modern ROV weapons is not yet widely understood. Improved batteries for electric vehicles also increases range. The issue of logistic support is somewhat useful in understanding use of ROVs for delivering explosives and again modern terrorist use changes the impact of that logistic support and is maybe less crucial in terms of systems. What is inescapable now and in the past is that ROVs offer an aggressor a safe way of delivering explosives, with the size of the explosive charge required having, of course, an impact on the vehicles that might be suitable. The key difference today is that technology has improved reliability of control systems, and also that technology is broadly available. However it is susceptible to technical counter-measures. In particular radio control systems are now consumer items and not limited to government enterprises. There are also some other parallels in terms of utilisation of captured weapons systems – and here I’m thinking of the way some Syrian jihadists have adapted captured armoured vehicles for suicide VBIEDS.

I recommend thinking in terms of tactical design – the systems outlined above all approached the target to a “control” point. From there the mode of control switches – and remote control takes over. It’s worth, as with any attack system, particularly terrorist attack using radio or other command systems, having a hard think about what defines that “control point”. What are the characteristics of that change over point that are needed, are chosen and utilised? Understanding those will help you develop some counter-measures. Modern day control points are perhaps less clearly defined than these WW2 examples, but the principle remains. Another thought that comes to mind is the importance of Technical Intelligence to the EOD operator. Put yourself on the shoes of an EOD tech 75 years ago – what would you want to know about the command and initiation system before you dealt with such an object? It may have no relevance today but as a “process” it’s useful to think through how you, a modern EOD operator, would deal with such things in a variety of situations – it’ll get your brain thinking, and that’s the best use for a brain.

Most of you will be aware of the command driven vehicles used by modern terrorist groups – various Jihadi ones, ETA, FARC and the IRA have all use such systems and others too are in the back pages of this blog site. But most importantly don’t be then thinking remotely driven vehicles delivering explosives are anything new – they are more than a century old and there are lessons to be learned still. From a historical perspective I’m intrigued by the German campaign in Crimea and the manner in which they used innovative weapons systems there – I’ll be digging further as it’s not a part of WW2 that I’m all that familiar with and instinct is telling there’s some interesting history. I have one wild reference to an ROV being used underground there which I’m trying to track down, and of course Russian defence of Sebastopol in the century before has been a subject of previous blogs. It’s strange how the patterns of explosive use over the centuries return to the same places. Sebastopol, Antwerp, London…