I’ve written over 30 posts in the last few years about explosive attacks on railways – you can see these from the categories link on the right hand column below. For this post, I’m returning again to Russian partisan sabotage attacks on the Germans. One of the reasons for my focus is the belief that the intensity of the attacks in Eastern Europe is largely underestimated. The more I look at these attacks the more intriguing it gets. I don’t claim to be anything other than a very amateur historian and I’ve learned a lot about the Eastern Front that I never knew, in general terms. Whereas I normally focus on tactical aspects of device design, this post is very much focused on the strategic. This post is less about the technicalities of the attack but more about the level of coordination and intensity of the attacks and comparing them to railway sabotage in Western Europe at a similar time.

I would suggest, if you haven’t already you read the earlier post on Ilya Starinov, one of the most important people in explosive sabotage history and probably THE most important individual. I see his fingerprints on much of what follows. I’d also recommend the post on Boer War railway attacks – which in WW2 terms are a most instructive historical campaign on a strategic level, with many similarities.

Now, as I have discussed before, railways make ideal targets for explosive sabotage. Here’s just some of the reasons why:

- Railways are an infrastructure target which can impact on a whole economy or military capability, in some cases with strategic effect.

- The scale of railways are too big for defensive forces to provide adequate security. Fundamentally a large railway system cannot be protected.

- The railways then provide high value targets (trains) at predictable times, (and no trains at predictable times too) making operations easier to plan.

- The kinetic energy of a train can be utilised by an attacker to increase attack effect. Remove just one rail or even the connection between two rails and a speeding train will do the rest of the damage for you.

- Railways offer either time and space for command initiated devices to be emplaced and initiated or known and repeatable mechanical opportunity to use a train-triggered switch.

- Responses post-attack are predictable and usually aligned geographically to the railway.

- Failed attacks can cause almost as much disruption as successful attacks, as devices need clearing.

I think the apogee of explosive attacks on railways came in three bursts on the eastern front of the Second World War, as the Soviets faced the Germans. The numbers of the attacks were quite remarkable, even if you view Russian claims very sceptically. The three key railway attack efforts were:

- Operation Rail War

- Operation Concert (sometimes referred to as Operation Concerto)

- Railway sabotage attacks as part of Operation Bagration.

I’m going to summarise these in turn. Each of these sabotage efforts were part of a strategy to disrupt German advances and also make the German defences much weaker. But first it’s important that we place the importance of the railway system in Eastern Europe in context. Railways in Eastern Europe were much more important than in Western Europe because there were few roads capable of taking significant traffic. If you wanted to do anything logistically “strategic” in Russia and Eastern Europe, you did it by rail. I’m going to give a link here to a fascinating article about how the Russians and Germans ran their railways in the war – you might think that would be dull dull dull, but by golly it’s an eye-opener. Of particular note are these things:

- There is a myth that the Nazis were the ones who got the railways running properly. This linked article demolishes that completely – it was the Russians who optimised the railways system so much better, and with a simple robust methodology.

- It is fascinating that when the Germans advanced into Russia they took over 40% of the Russian rail network – but only 15% of its trains. And that’s a big problem if you then have to find hundreds of trains and carriages (also with a different gauge).

- It’s important to understand the logistic manner of functioning with “depots” serving areas of track – the locomotives stay attached to the depot and shuttle backwards and forwards – the carriages are passed like a baton.

- Russians ran their trains slower, all at the same speed – conserving engines and carriages and train lines. This also allows for simpler control mechanisms (even if it’s a man with a flag). The Germans tried to run their trains at a variety of speeds, leading to more wear and tear and a much more complex control system to allow for “overtaking”.

- The numbers of people involved in railway logistics on both the Russian and German side is stunning.

Russian partisans were made up, in broad terms, from the following:

- Soviet soldiers who had been bypassed by the German advance. All soldiers were instructed to undertake sabotage operations in these circumstances.

- Captured Soviet soldiers who had escaped

- Civilians from the overrun population, usually communist party functionaries. Some of these formed more formal “Destruction Battalions” including retired soldiers and factory workers. Their prime mission was originally securing the Soviet rear area and destroying infrastructure as the Russians retreated, but once overrun they became partisans in effect, with at least some sort of command and control, and relevant training.

- NKVD or military personnel brought in by plane and parachute.

- Other partisans of all sorts of backgrounds.

The command and control system was flexible and changed as the war progressed – becoming more organised as time passed. So let’s look at the three key Russian rail sabotage efforts.

Operation “Rail War”

This operation occurred during the Battle of Kursk as over 100,000 partisans tried to disrupt German rail activity, disrupting German reinforcements and logistic supplies. This was in July and August 1943. This operation built on the experience of an increasingly effective partisan campaign over the previous year – in the previous winter 225 German trains were derailed, and much other infrastructure attacked. Coordination was handed over from the NkVD to other Russian command structures and became much more coordinated. In Belorussia alone 123 partisan detachments were assigned to demolition activity – often, but not always, with explosives. Literally hundreds of thousands of pieces of track were either blown up or removed. As a cross reference, in July 1943 alone, the Germans reported at least 1,100 separate railway attacks. Then, during the nights of August 3rd and August 4th, the German Heeresgruppe Mitte reported 4,100 railway demolitions. A German source puts the figure even higher for the whole front suggesting 10,900 demolition charges were laid on the night of 2-3 August alone, with over 8000 functioning as intended and the remaining rendered safe by German EOD, many of them “daisy chains”. That’s an incredible number. It seems some attacks were carried out by Red Army demolition units of 30 men each (probably sent by Starinov) flown in to support Partisan activity during the Operation. Is this the first effective use of Starinov’s “Spetznats”? These latter groups seem to have focused on undertaking attacks with more complex devices.

Operation “Concert”

This was a strategic offensive to against German rail communications and logistics during the Battle of the Dnieper and Russian Operation Suvarov, an attack in the direction of Smolensk. It took place immediately after Operation Rail War, from 19 September – 1 November 1943. This was a wide ranging set of attacks from the Baltics to the Crimea. According to Russian sources it involved 193 partisan units, totalling more than 210,000 men. Railways were disrupted across a 560 mile front, to a depth of 250 miles. One source suggests that German logistic movements were restricted by 35 – 40% , In Belorussia alone, partisans claimed to have destroyed or damaged 90,000 individual tracks, 1,061 trains, and 72 railway bridges during this 6 week period. Two examples of the intensity of explosive sabotage operations during this time are as follows:

- On one 30 mile stretch of the railway to Minsk, there were 643 explosive demolition attacks on a single railway. On another 40 mile stretch there were 580 attacks.

- At one stage on this Minsk line the situation got so desperate that reinforcing troops were off loaded from trains and stationed at 20 ft intervals to guard against the attacks.

Sabotage in support of Operation “Bagration”

At least 150,000 partisans took part in sabotage operations in support of Operation Bagration, the major assault that occurred roughly the same time as the Allied attacks on Normandy. In many ways Bagration was much more successful than the Normandy attack in terms of the advances made, albeit at heavy cost. In the West we think of “Normandy” as the key battle in WW2 – but if you look at the number of troops and the distances involved, Bagration was a much bigger affair. Partisan disruption of German logistics, by explosive sabotage on railways, played a crucial role. On a single night the night of June 19th 1944, there was more than 9,500 explosive attacks on the German occupied railway infrastructure. The Soviet offensive with conventional forces started three days later, and they were able to overcome German defenders who had no supplies and no reinforcements. It is interesting to consider this three day gap, which perhaps allowed the Germans to catch their breath. I don’t quite understand this pause. One explanation might be that the partisans simply used up all their explosives on the first night. Another might be that the Russians expected the Germans to denude their front lines of infantry units to guard the railway lines. In any event, two and a half months later, the Soviets has advanced almost 600km and most of the German occupied Soviet Union was retaken. (By comparison by that time the allies had got to Paris, about 25okm.) It is clear too that the ability of the partisans, in terms of setting and emplacing explosive devices had improved, probably due to Starinov’s influence in training and device design. Similarly, coordination, control leadership and planning had improved too, making partisan operations more effective, but perhaps not fully optimised.

As the war progressed and particular after responsibility was passed from the NKVD to other military structures, Russian support and coordination to the partisans improved, in terms of direction and resources often airlifted in to the vast spaces of Eastern Europe.

Elsewhere in Europe

Partisan style attacks of course occurred in Western Europe and it is useful, where possible, to compare these against the scale of the Russian partisan efforts.

During October and November 1943 (a comparable time period to the Russian Operation Concert above) the Vichy French police reported more than 3000 attempts made by the resistance to attack the railway system. The biggest comparable effort was “Plan Vert” by the French resistance movement, in support of the forthcoming Allied Normandy Landings and subsequent battles. Around the time of the landings in Normandy, 486 attacks were made on the French railway infrastructure by the Resistance preventing German reinforcement on a number of lines. This, while significant, appears to be an order of magnitude smaller than the Russian efforts. Of course, the two theatres are not directly comparable in terms of the importance of the railway infrastructure. In Northern France the optimum logistic infrastructure were the roads. Throughout the whole of the “OB West” administrative sector (which equate to the Western Front against the Allies,) 500 locomotives were destroyed by sabotage or air attack during March 1944, but there were 500 sabotage attacks on railways in France in April 1944, much of which had an impact on the supply of concrete and steel to build the Atlantic Wall. In the West, the Allies relied predominantly, but by no means exclusively, on air attack to disrupt the railways. From all sources, however rail traffic was reduced by 60% from 1 March to 6 June 1944. There were, according to some sources, 1,800 sabotage attacks on French railways between 1 March 1944 and 6 June, and 2,400 rail targets hit by Allied bombers. But compare that 1,800 figure over a 4 month prior to the 10,000 plus on one night in August 1944 on the Eastern front, (and that’s a German figure), and I’m not saying that the French railways were a similarly important target – but whatever the measure, the Russian partisan attacks in the East were remarkable in their number, and I suspect in their effectiveness.

Of course there were other successful rail attacks on the German forces elsewhere in Europe, but these are relatively few and far between and simply get reported better than the thousands of attacks on the Eastern Front. In particular there were quite a number of attacks by Polish resistance forces, who on one occasion cut all railway lines to Minsk, and who carried out “hundreds” of explosive sabotage operations on the railway during the war. Of course the Polish attitude towards the Russians was complicated which affected their operations.

It is also important to recognise that not all sabotage was by the use of explosives. Unbolting tracks, adding grit to lubricants, allowing boilers to overheat, allowing trains to travel too fast or too slow, or making deliberate mistakes with railway points all count towards a broader sabotage effort.

In general in the West we assume , wrongly, that the sabotage by the French resistance was a large scale operation, and we note other individual attacks across Europe or historical campaigns such as those of Lawrence and Garland in Arabia in the First World War. The truth is, though , that they are nothing, a pinprick compared to the huge efforts of the partisans in Eastern Europe between 1941 and 1944.

Assessment

So my assessment is that the sabotage attacks on German rail infrastructure was significantly greater than in the West and the impact of this is probably largely underestimated. The partisans showed that if necessary they could mount 10,000 explosive attacks in one night, and maintain many thousand attacks a month across most of the Eastern front. I can think of no other sabotage or explosive campaign in history with that level of intensity. It might have suited Russian propaganda to downplay the scale and proportional effort and effectiveness of rag-tag partisans rather than more formal Russian forces, just a much as they might exaggerate the effectiveness of individual local partisan detachments. Quite often though I have found German sources to present even higher numbers, which leads me to believe that this incredible level of operational activity was genuine. And, the Germans were better at record keeping than the Russians. But we should also remember that in the East the rail systems were much more crucial to military success, and circumstances allowed a much more “permissive environment” than in Western Europe. Other factors leading to this success include:

- Significant numbers of partisans available, often from overrun Soviet Army units, in the area behind German front lines.

- A huge geographic space where large numbers of partisans could “disappear” into, and regroup, resupply unhindered by occupying Germans who were focused on the front. The imperative driven by Hitler himself was to throw any and every German unit into the formal front rather than focus on securing rear areas. This gave the partisans a freedom of movement. The Germans simply didn’t have enough troops to secure their rear areas and supply routes and guard the railway system consistently. Furthermore, most of the troops securing rear areas did not have transport. Nor were there enough troops to guard prisoners or feed them. If you were one of a thousand Russian troops being guarded in dense woodland by three second-rate Germans with bolt action rifles and pocket full of ammunition and one horse between the three of them, and you weren’t being fed, would you sit tight in the snow or simply walk away and become a partisan? That’s the reality of the situation.

- Russian roads being so poor that it was impossible to move any amount of supplies by road, meaning the railways were even more important. The railway lines where everything – what else was there for the partisans to attack if it wasn’t actual military units? So the most efficient form of attack was an attack on the railway that risked less.

- The temperature – German locomotives converted to run on Russia gauge tracks, or tracks changed to suit them, were not designed to operate in the winter temperatures of Russia. Damage to German run trains was harder to fix.

- A Russian “tradition” of partisan warfare going back to Napoleonic times.

- Poor German logistic management of railways, in some respects.

- Ilya Starinov himself.

Overall, it is clear to me that partisan explosive attacks on the railroads significantly enabled the defence of the Soviet forces in the summer of 1943 and their subsequent advances. Partisan attacks were intense in number, flexible and by the latter part of 1943 well controlled and supported from Russia. It seems to me that in general they often had an 80% successful rate in terms of devices that exploded versus rendered safe by EOD. That’s pretty high. This wasn’t always the case, and in some areas that ratio was reversed, probably due to poor training. I have no doubt they enabled the success of Soviet Forces in the East. German responses to the explosive threat to the railways was occasionally innovative but hampered at every turn by the fact they were deep in occupied territory, on an extended supply chain with locals who if they weren’t unsympathetic to start with became increasingly so as the war progressed and they suffered from the fundamental flaws inherent in a fascist invading army. The Germans were never able to find the military numbers to secure the railway. I have no doubt that the partisan sabotage efforts shortened the war in Europe and allowed the Russians to reach Berlin well before the Western Allies. But that’s not because the Western allies failed to attack the rail infrastructure on “their side of Europe”, it’s just because railways were much more important in the East and the Russians realised that and exploited it.

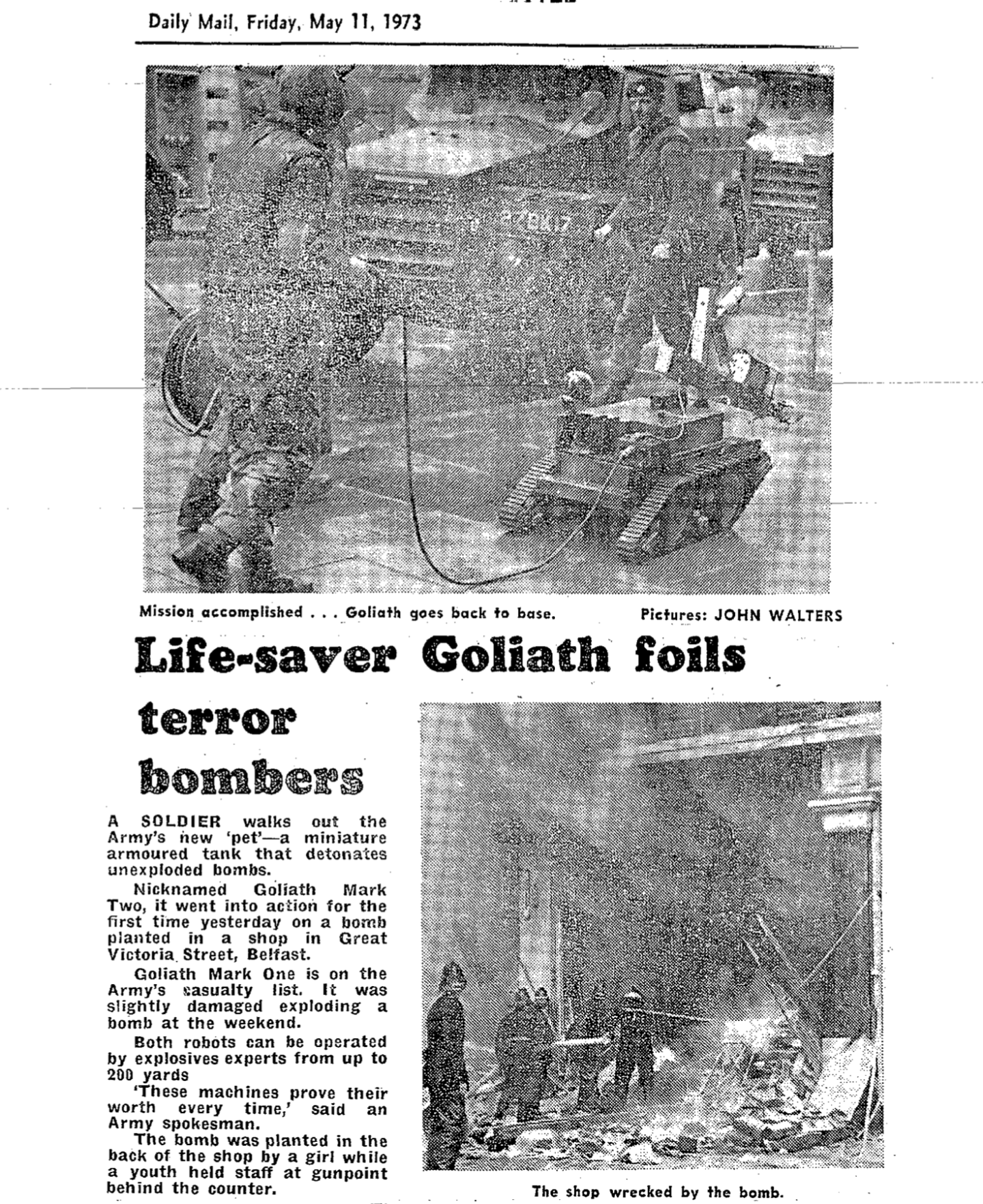

One of the sources I have used for this post also includes some very interesting assessments of German counter-sabotage efforts – well worth a read if you have the time, here. You should note it is drawn mainly from German sources. I’m also looking at similarities between WW2 sabotage operations and what the US/UK and UK faced on operations in Iraq and Afghanistan since 2003. If you read the lessons learned in the document linked above about the experiences of the Russian partisan efforts, while bearing in mid what occurred in Iraq in 2003/2004, it will make you wince, so clear are some parallels. The parallels between aspects of the counter-sabotage operations and engagement or otherwise with local forces is particularly pertinent. It’s not nice to see similarities between certain Nazi strategies and operations and your own, but there it is. Do you think what happened in the Anbar Awakening and the “Sons of Iraq ” was an innovative idea? Think again. The Germans used White Russian cossacks in attempts to secure certain areas, and there were a number of other strategies which seem only familiar for an invading Army. If I were to be really cynical, (and I can be) there’s also some similarities in Northern Ireland in the 1970s.

Although this post is all about strategy and not my usual focus on technical matters, I found a few intriguing technical references that I intend to follow up on.

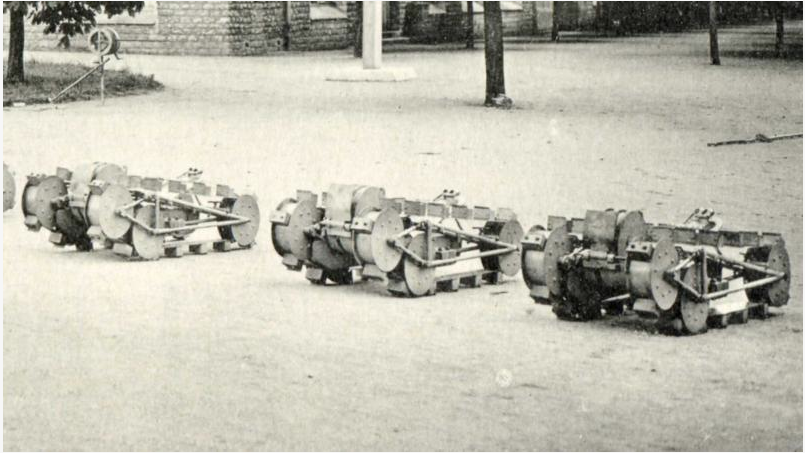

- The first is from the period of the summer of 1943, about the period of Operation Rail War. There is talk of the Germans encountering a new “small” explosive charge provided from Russia to the partisans, which is “daisy-chained” along a length of railway in a series of charges – one report suggests as many as 500 charges in a single daisy chain…. very intriguing and I’ll hunt out details in coming weeks if I can.

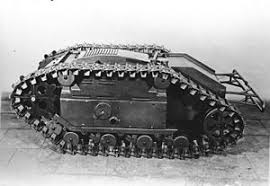

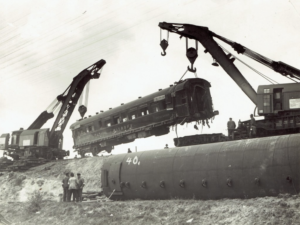

- The second is reference to a specific counter measure – the Germans apparently in response to pressure sensitive explosive devices on the tracks filled a couple of spare carriages with rocks and placed them at the front of their trains, as sacrificial carriages.

- Some other countermeasures. During Operation Concert one countermeasure used by the Germans was the use of searchlight units set up at intervals along vulnerable tracks – the exact technique had been used by the British Army to counter Boer IEDs on railways in South Africa 40 years earlier. In other areas some sort of “alarm” system was set up but as yet I have no details, but the impression I have was this was electrical, I think utilising microphones because the oblique report I have seen suggests they were linked to “listening posts”. Anti-personnel mines were laid by the Germans in places alongside railways where they expected attacks. It would appear that the Germans booby trapped some telephone line poles, that they expected partisans to fell, but the technique is not clear. In another similar approach to the British countermeasures in South Africa 40 years earlier, the Germans manufactured “bicycle trolleys” for troops to patrol tracks.

- A reader of this blog has also flagged to me that Starinov co-authored another book, in 1961, about the campaigns above called “Mines against the German rear area”. I don’t think it has been translated but I suspect it’ll contain more interesting detail. I’m searching for a translation.