In May 1992 I was just starting my second tour in the EOD world. One of my jobs was to disseminate to my colleagues information on technically significant IED incidents, and the following was one of those incidents, and seemed very innovative. Given the ongoing discussion about “Backstop Borders”, or not, with the Irish Republic, it’s also quite pertinent.

In 1 May 1992, the British Army manned and ran a checkpoint ay Cloghoge on the Northern Ireland/Irish Republic border adjacent to the main road between Dublin and Belfast. This is about as far South as South Armagh goes, and in those days there was a very high level of threat from the Provisional IRA. The main railway line also sat right there, and the small post, quite heavily protected, was right next to the road and the railway. It was normally manned, if I recall correctly, by about a dozen soldiers, providing “cover” and assistance for the police stopping the cross-border traffic at the check point. In Army terms the checkpoint was called “Romeo 1-5” (R15).

The Provisional IRA mounted a clever attack on the checkpoint. They stole a mechanical digger, and separately, a van. They loaded approximately 1000kg of home-made explosives in the van. Using the digger they made a makeshift ramp from the road, up to the railway lines, manoeuvred the van up the ramp then fitted the van with railway wheels. The digger was then used to lift the van, with its railways wheels, onto the the railway line (it wasn’t that busy a line and it was the middle of the night). All this happened out of sight of the checkpoint, at about 800m south of the border.

The van was fitted with a spool of cable, to initiate the device, and the cable fed to a terrorist who could see the checkpoint or someone who was in radio contact of someone who could see the target. At about 2 o’clock in the morning the van was set off in first gear, with no driver, towards the checkpoint paying out the spool of cable.

The Army sentry on the checkpoint, Fusilier Grundy, heard and then saw the approaching vehicle bomb and raised the alarm. Most of the occupants of the checkpoint took cover. Fusilier Grundy, correctly assuming this was a threat to his life and those of his team, opened fire in an attempt to disable the vehicle bomb. at 0205hrs the device was exploded next to the concrete sanger containing Grundy, killing him and throwing the ten ton protective sanger into the air. The remaining soldiers survived in a shelter, built to protect them if a vehicle bomb was delivered by road. The replacement to this checkpoint was removed when the Good Friday Agreement came into effect.

I duly wrote up a technical report to the teams I supported (I was on mainland UK at the time), and highlighted that this innovative technique had never been used before.

Or so I thought… But this is “Standingwellback” ain’t it, where I delve back in history. So check this out:

On 31 October 1943 the Germans were holding and guarding a railway bridge on the Ubort River in the Ukraine, West of Kiev. A Soviet partisan group led by an NKVD Major called Grabchak decided to use an “innovative” method to attack the strongly defended, strategic bridge. The area around the bridge was heavily mined, enclosed with barbed wire, there were several machine gun posts and a large garrison protecting it with mortars and other heavy weapons.

Twice a week the local German commandant travelled down the line to inspect the defences at the bridge from his base a few miles away. He invariably travelled to the bridge by a “special section car”, a small vehicle that was mounted on the railway line rails and used by railway officials for inspecting the line. As far as I can work out this was pretty much a road car fitted with railway wheels. Grabchack and his partsians, over a two week period, made a “replica” section car. The base of the vehicle was fitted with five large aircraft bombs. The fuzing arrangement was simple and ingenious. They knew the height of the cross bracings on the bridge. They fastened a long pole, upright between the bombs. Towards the base of the pole was a pivot point and at the base, a length of wire leading to the pin of a grenade fuze connected to the main charge explosively. So the concept was that the “section car” would be sent down the railway, and as it started to cross the bridge, the pole would hit the cross braces of the bridge, pulling the pin from the grenade fuze. To add to the effect of the “expected” section car, two dummies were made, dressed in German uniforms, one an officer, the other a driver, and sat as realistically as possible in the car.

At 4pm, on 31 October 1943 the car was carefully placed on the rails about 1km from the bridge, just out of sight, near the village of Tepenitsa. It trundled down the line towards the bridge, and seeing it coming a guard opened a barrier and let it enter onto the actual bridge itself, presumably saluting smartly as it passed by. There, the device exploded, damaging the bridge severely. Interestingly the German forces put out some propaganda that the device was a suicide bomb, driven all the way to the bridge on rails from Moscow, by “fanatical red kamikazes”. Apparently several more of these railway delivered IEDs were constructed and used but I can find no records, which given it was 1943 and the middle of a war full of sabotage operations is not surprising.

I have written a previous piece about trains loaded with explosives in Mexico in 1912, “loco-locos”, here.

So, the analysis of these incidents suggests the following:

1. There are several instances, historically, of trains or vehicles on train lines being the delivery method of getting explosives to targets. A variety of switching methods is possible. The technique can cause significant surprise, and such vehicles can carry sufficient explosives to overwhelm hardened targets.

2. Apparent innovation isn’t always new. Especially on standingwellback.

3. Border crossings are tricky, whichever way you look at it.

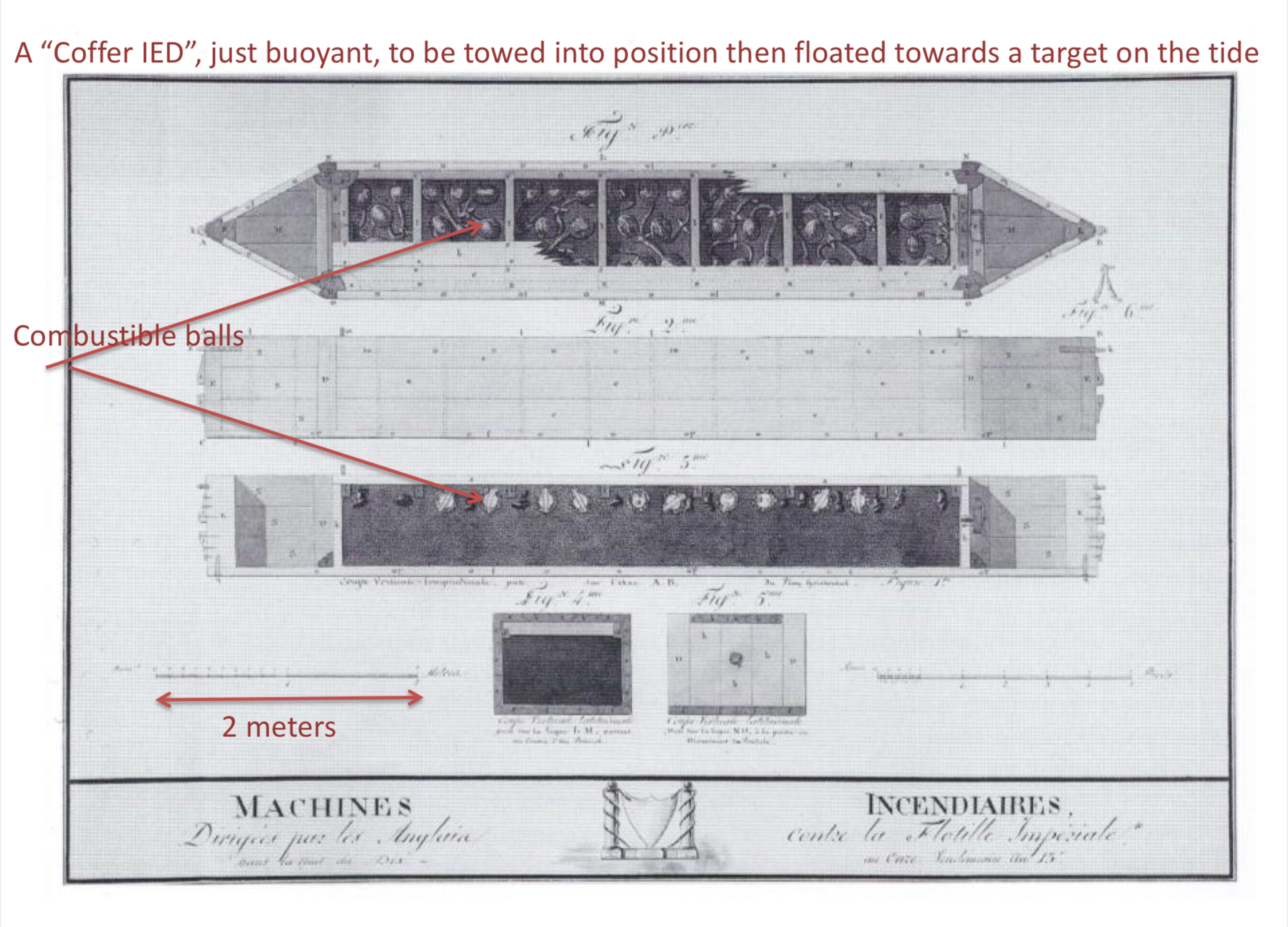

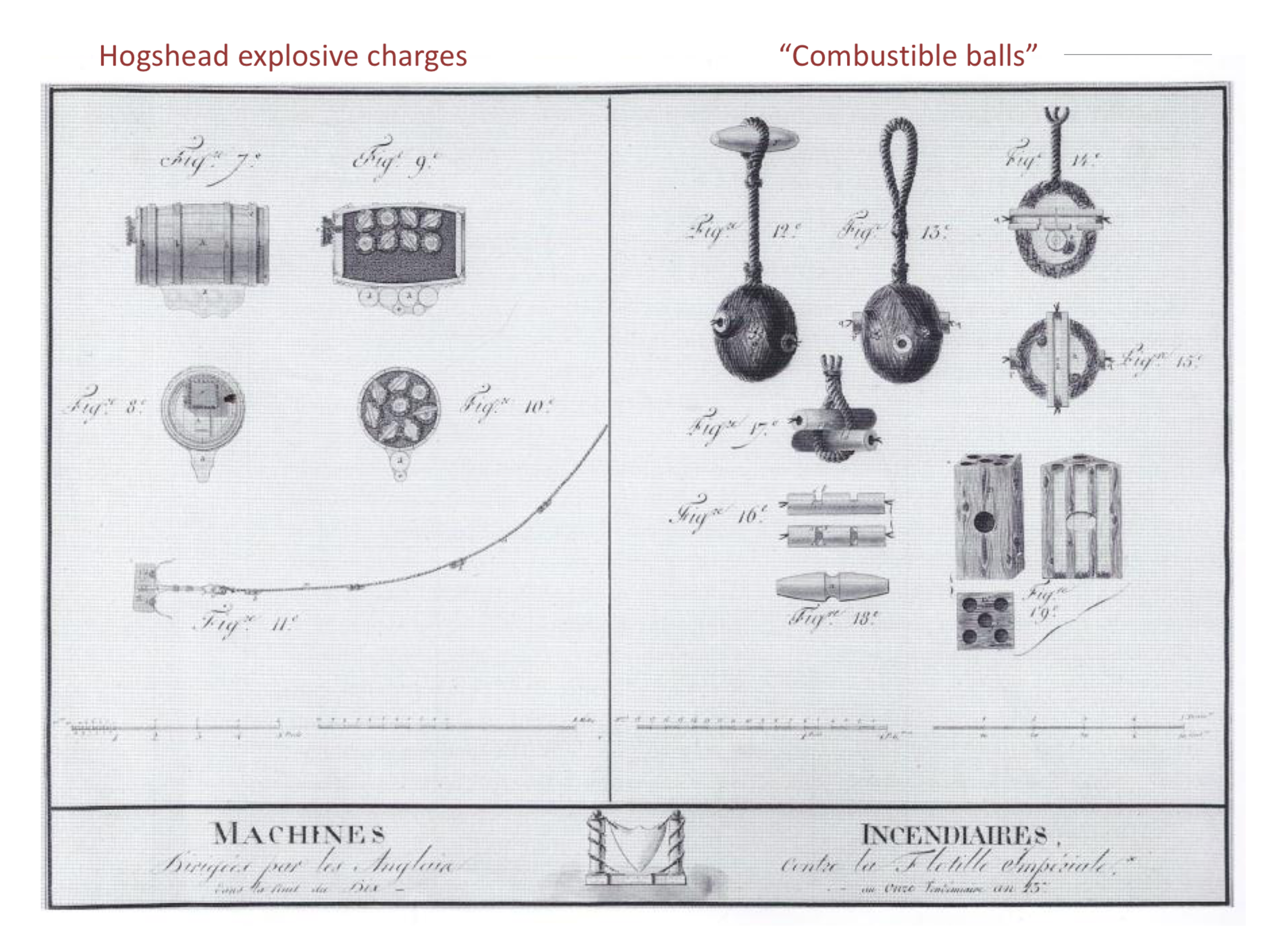

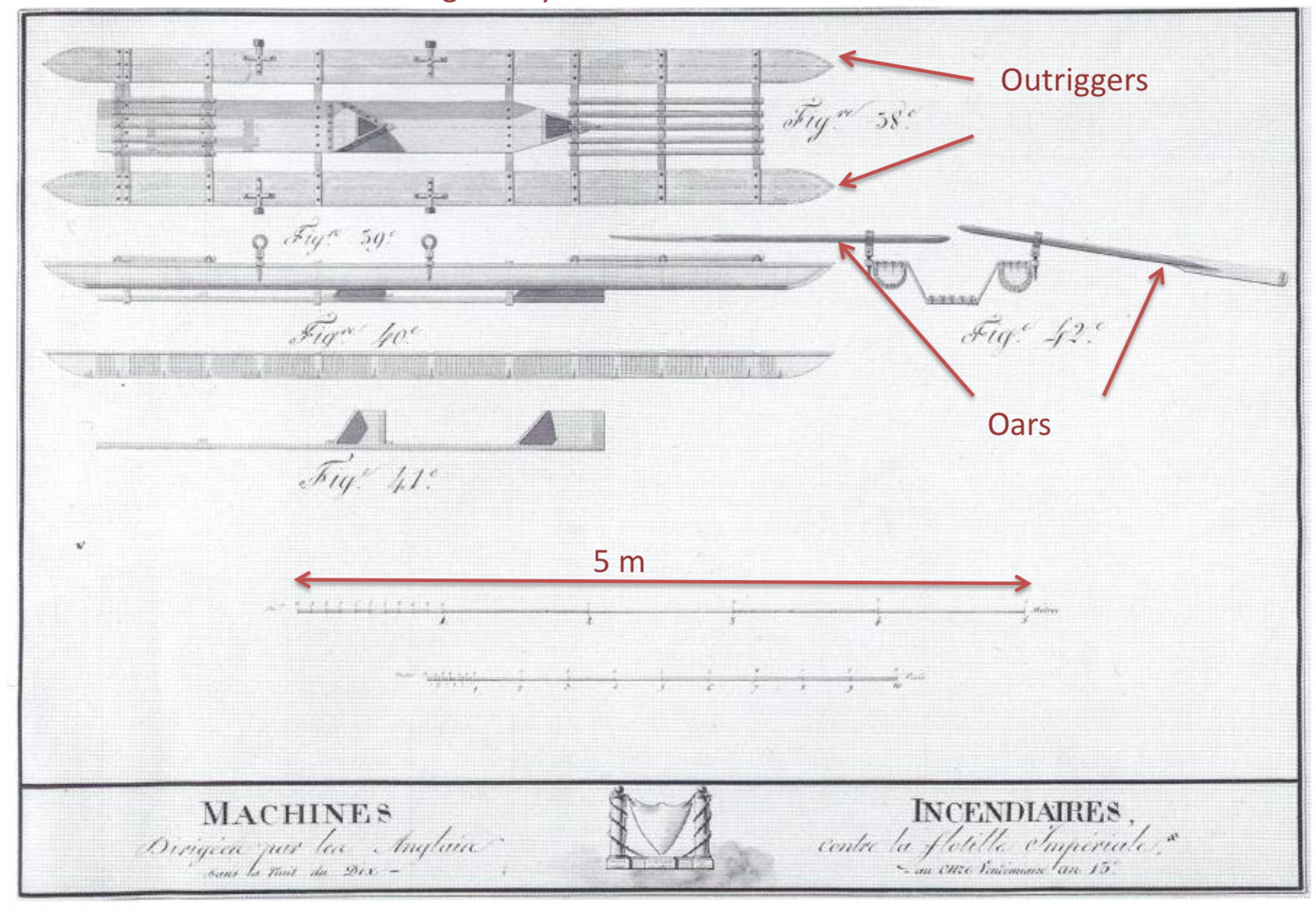

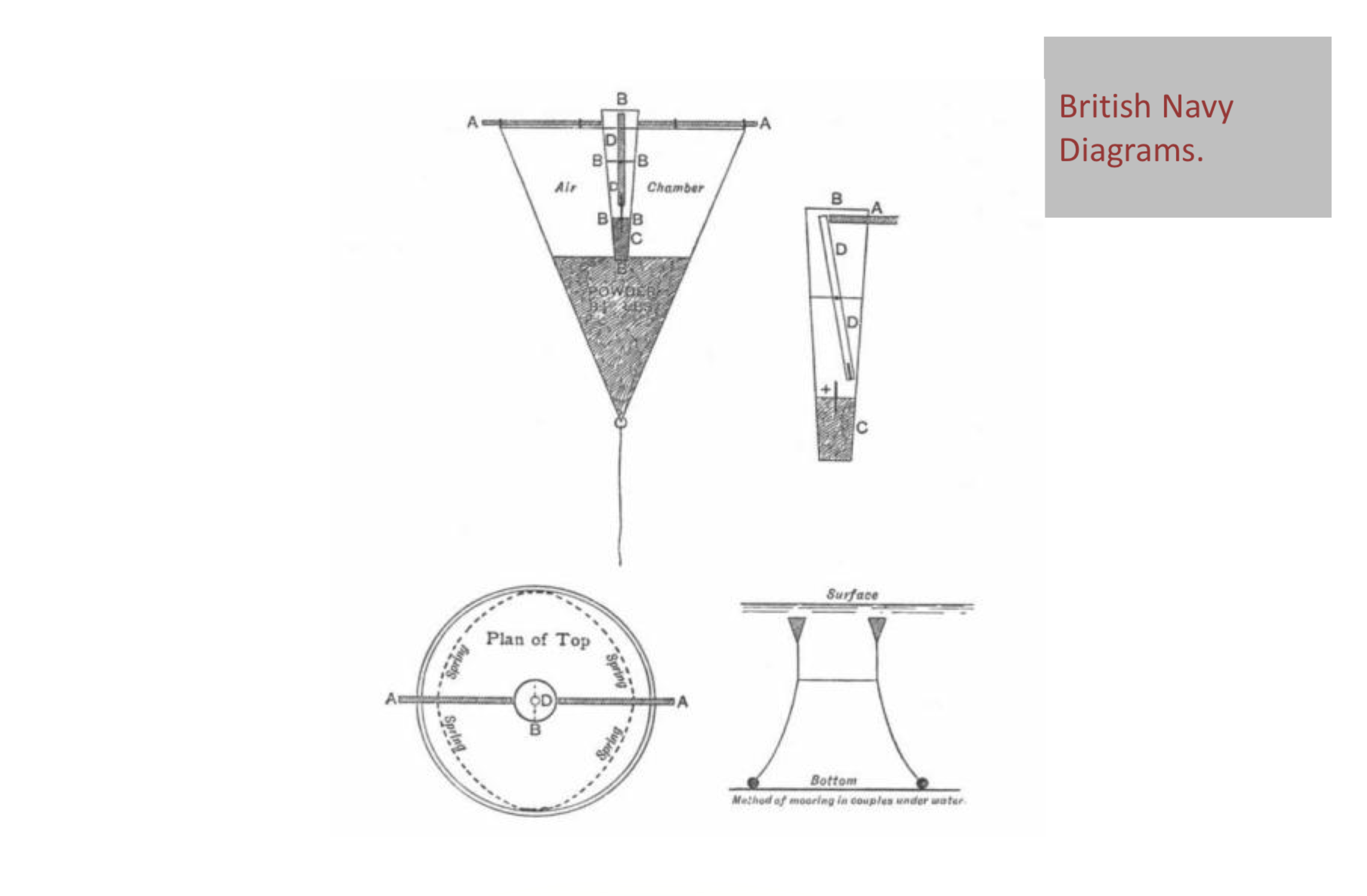

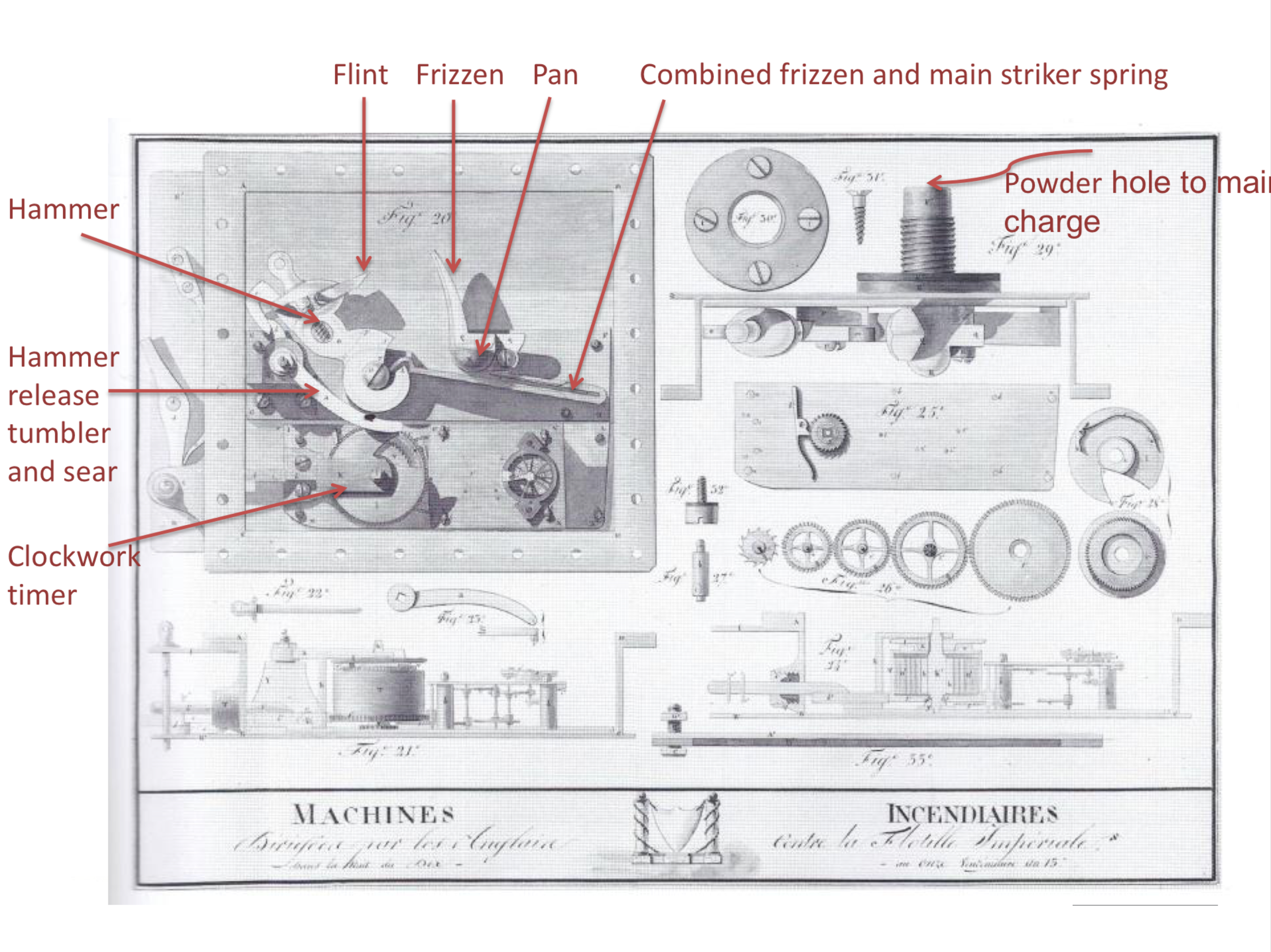

This clockwork initiation mechanism was attached to a main explosive charge. The main charge was a large sealed canoe shaped pontoon, described as a coffer. Two of these were attached to make a barely buoyant twin raft with a rowing position in the middle.

This clockwork initiation mechanism was attached to a main explosive charge. The main charge was a large sealed canoe shaped pontoon, described as a coffer. Two of these were attached to make a barely buoyant twin raft with a rowing position in the middle.