In an earlier post I suggested that the first electrical command wire initiated device appeared in the American Civil War. This was incorrect, as I believe the truth is that such things were first developed by the Russians in the 1830s as electrically initiated sea mines and later used in the Crimean war by the Russians . A “forgotten theatre” of that war was a series of naval engagement in the Baltic as the British and its allies blockaded Russian ports. The Russians protected their ports with ingenious improvised sea mines and a number of these were electrically initiated.

These first “galvanic” initiated mines were developed by Engineer-General Karl Shilder, who was a senior engineer in the Russian Navy – and he had a chance encounter with Alfred Nobel’s father, Immanuel Nobel in the late 1830s. Immanuel Nobel had developed the concept of a rubber backpack containing explosives for use by the military as a contact initiated explosive mine. He failed to gain interest from the Swedish military so took his ideas to the Russians. Shilder was on a committee set up by the Tsar to investigate electrically initiated mines. Nobel suggested his contact mine as an alternative and subsequently the idea was presented and demonstrated to the Tsar who rewarded Nobel with 3000 Roubles. Nobel set up a facility to develop the concepts further and succeeded in a trial in 1842 to blow up and sink a three-masted ship – gaining a further substantial financial prize from the Russian government.

When the Crimean war began Nobel’s mines and other command-initiated devices were used extensively on land and sea, and in particular to protect the Russian naval port of Kronsdtadt on an island in the approaches to St Petersburg. A British operation to recover and exploit this new foreign technology was mounted and Russian mines was recovered and carefully tested. Other British attempts to exploit the Russian technology were less successful – a number of senior British naval officers, including the commander, Admiral Dundas were badly wounded when examining recovered Russian devices. Here’s a diagram of a Russian contact mine, a description of some early naval EOD actions, technical device exploitation and a fascinating account of the stupidity of senior officers, twice in one day – all in one:

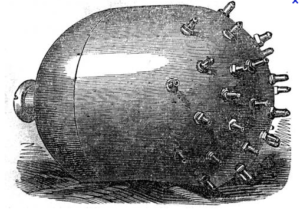

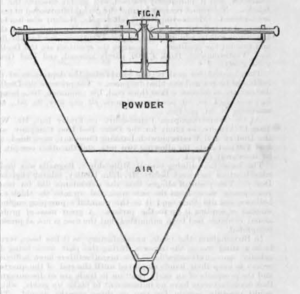

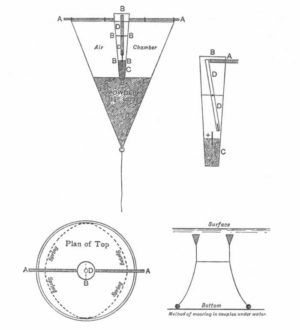

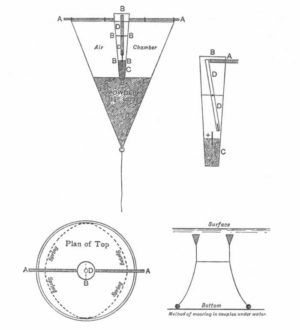

They are made cone-shaped of strong zinc, about two feet deep, and fifteen inches wide at top. The bottom holds the powder, about eight pounds; the top is full of air, to keep it up; a strong tube (B B B) goes through the top, and reaches the powder; a small tube about the size of a lead pencil is hung in the centre of the large one (D D) – it pivots on its centre; and fixed in the bottom of the large tube, in the little chamber of priming-powder (C), is a small glass tube (+), sticking up into the bottom of the small tube. You will see that if anything pushes the upper end of the small tube on one side, as I have tried to show in figure 2, as it is pivoted in the centre, it must break off the glass tube, which is filled with some ignitible stuff, which fires the priming-powder (C), and of course explodes the machine. Now the two thin tubes of iron on the top (A A) slide to and fro, out are kept away from the tubes by slight springs. On being touched by a ship’s side, or even pressed with a finger, they shove the small tube aside, as in figure 2, and explode the machine. How any were hauled into boats without exploding seems marvellous; but some lost their tubes when canted up to be hauled in; others had been put down with caps on the tops, which prevent their going off. These ought to have been removed; but the parties putting them down had been so afraid of them, they had preferred leaving them safe for us to risking removing the caps themselves. I don’t know what the Grand Duke will say if he knows this! Admiral Seymour and Hall got one up, and hauled it over the bows of the gig. How the little slides were not touched is wonderful. It was then passed aft; and the master of the fleet joining them, they, thinking it was damaged with wet, got discussing the way to set it off. Stokes touched the slide, shoved the tube a little on one side, but evidently not enough to break the glass tube. They then took it to Admiral Dundas, and again they all played with it; and Admiral Seymour took it to his ship, and on the poop had the officers round it examining it. Hall, being in the act of hoisting a second one, was on the quarter-deck. Some of the officers remarked on the danger of its going off, and Admiral Seymour said, ‘Oh no; this is the way it would go off,’ and shoved the slide in with his finger, as he had seen Stokes do it. It instantly exploded, knocking down every one round it. As Hall looked round he saw the captain of marines, a son of Sir John Louis, carried down the ladder, with every bit of clothes burnt off him and covered with blood. He then heard, ‘The admiral is killed.’ The latter was lying insensible, his face covered with blood; but he soon recovered, though very seriously injured in one eye and the head. The poor captain of marines had pieces of the machine in his legs, besides the burns. Pierce, the flag-lieutenant, much hurt, a piece of iron going through the peak of his cap, and knocking it into the mizzen-top, but not touching his head; a young volunteer also. The signalman holding it up at the time not very much hurt, though burnt; and one lieutenant and the chaplain, though next to Admiral Seymour and close to it, only had their hair singed, and were not hurt at all. Two or three men also slightly wounded. It is a wonderful escape, for pieces of it flew down the main hatchway; and we know that the Russians getting one into a boat exploded it, and killed seventeen men. Admiral Seymour is much less hurt than was first supposed, as he is able to sit up to-day; but concussion of the brain is what they fear. He can see a glimmer of light with the eye, so it is hoped he will recover the sight. The marine officer’s is the most dangerous case, but it is hoped he is doing well also.

The extraordinary thing is that the same evening Admiral Dundas and Pelham were examining a tube; so Caldwell went and got an empty machine (that had been cut open) to put the the tube in, to examine how it explodes. While they were close round. it, the admiral shoved the slide, and the tube exploded, shooting up in the middle of them, and hurting the admiral’s eyes so much that they were looking inflamed and bloodshot yesterday morning when he was explaining all this to me.

Moral of the story – don’t let senior officers fiddle with recovered devices. In future blog posts – How the US Army studied the Russian experience of contact and command wire initiated devices and did or didn’t employ them in the American Civil War – and the strange story of another US-Russia connection regarding command wire IEDs.

Update on Sunday, October 30, 2011 at 6:32PM by Roger Davies

I should make clear that the Russian experiments only just preceded perhaps more successful US experiments in electrical mine initiation. In 1841 – 1843 Samuel Colt demonstrated successfully on a number of occasions electrically initiated sea mines on the Hudson and then Potomac rivers sinking a number of target ships. Later developments were undertaken by Maury, a confederate naval officer in the 1860s

Update on Friday, September 28, 2012 at 6:14PM by Roger Davies

see later post http://www.standingwellback.com/home/2012/9/26/siemens-tangents-command-wire-ieds-of-1848.html